Use of veterinary point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has increased as technological advances have improved accessibility. In a survey of general practitioners, 53% of clinics were reported to have an ultrasound machine, and 45% of clinicians reported performing ultrasonography >5 times per week.1 Proper training and clinical reasoning are essential for interpreting, applying, and integrating POCUS findings to avoid misdiagnosis, delays in patient management, and patient harm.

Following are the top limitations of POCUS in daily practice, according to the authors.

1. Possible Misinterpretation Due to Overconfidence

Understanding personal limitations regarding POCUS is important because interpretation of findings can be subjective, and incidental or unexpected findings that exceed operator comfort or knowledge may be detected. For example, when the abdomen is scanned for free fluid, an abnormal region near the pancreas with masslike characteristics may be identified and misinterpreted as a neoplastic process arising from the pancreas. In general, incidental findings outside operator comfort or knowledge should be documented for follow-up with an experienced sonographer.

Ruling in specific pathology on POCUS via binary (ie, yes or no) questions is typically easier than ruling out specific pathology; a negative finding does not exclude pathology because of the limited, focused nature of the examination. For example, ultrasonography is more sensitive than radiography for detection of small volumes of abdominal effusion, but fluid may be missed if the probe is not placed where fluid has accumulated.

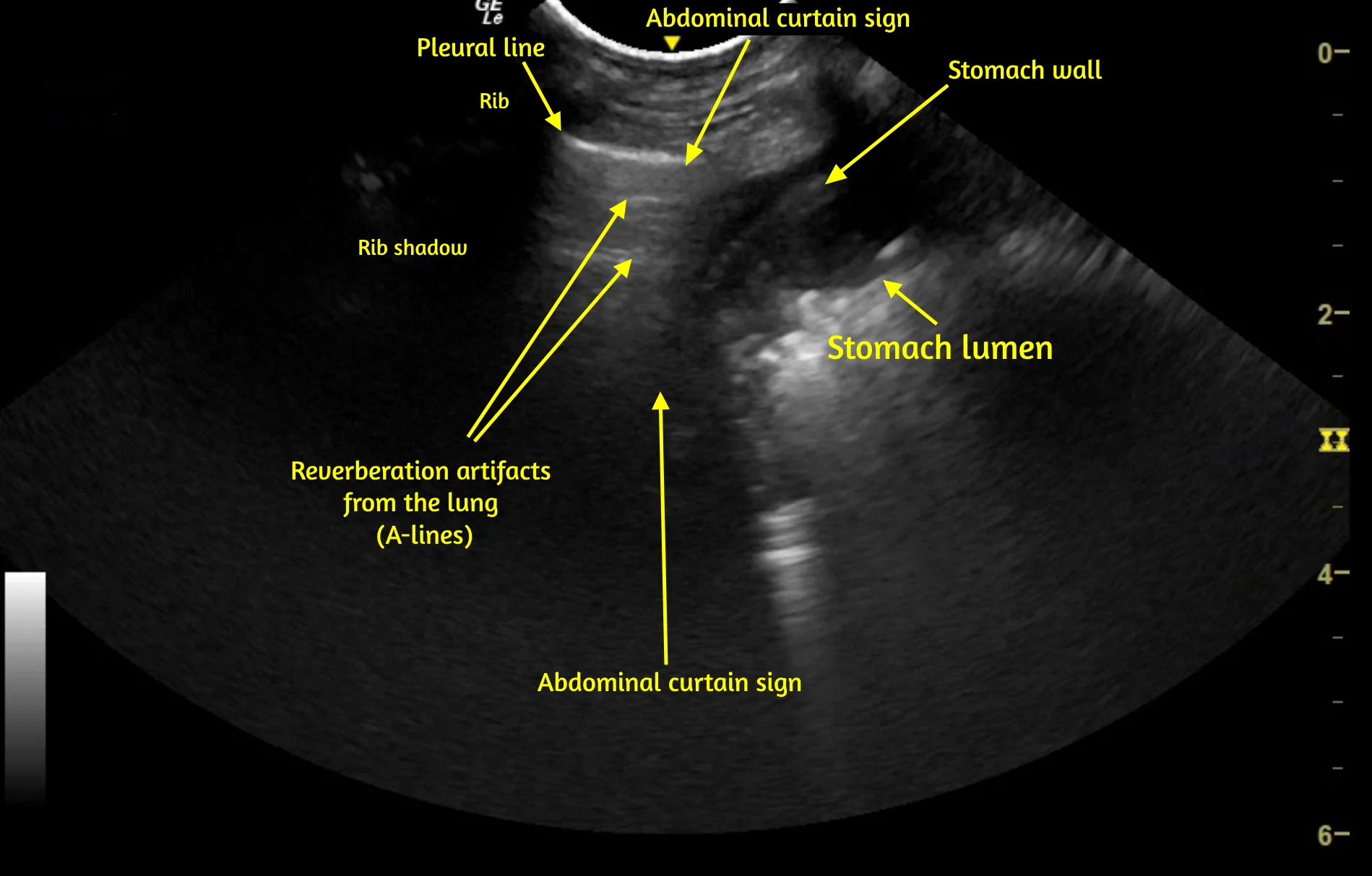

Familiarity with normal sonoanatomy, machine functions, image optimization, and sonographic artifacts that can result in false-positive or false-negative POCUS findings is also important. For example, abdominal structures below the caudal ribs can be confused with lung or pleural space pathology (Video 1), and rib or GI gas shadowing can obscure underlying structures, including pathology.

VIDEO 1 Pleural space and lung POCUS shows the left caudal lung border between the lung and abdomen. The vertical line (caudal lung border) that shifts cranially and caudally with respirations is the abdominal curtain sign. Caudal to the curtain sign, a small amount of liver is visible within the abdomen, followed by the stomach wall and gas and ingesta within the stomach lumen. The stomach wall can be misinterpreted as pleural effusion or stomach contents misinterpreted as lung consolidation if the operator is not familiar with the curtain sign. A labeled still image from the video is available below.

The learning curve for POCUS varies depending on which binary question is asked, and operators should be aware of personal limitations when asking specific questions. For example, an operator not comfortable assessing left ventricle function on cardiac POCUS can still locate and look at the left ventricle, which may influence clinical decision-making, but the findings should not be emphasized or used as sole diagnostic criteria until the operator is more comfortable with obtaining and interpreting left ventricular findings.

2. Lack of Consensus Regarding Standardization & Protocols

Lack of consensus regarding POCUS nomenclature, sonographic characteristics required for diagnosis, and optimal protocols for veterinary patients can cause confusion, even among clinicians in the same practice, which can affect patient handoffs and care. For example, a common statement is that occasional B-lines (ie, vertical hyperechoic lung surface artifacts that increase in number when lung density increases; Figure) should only be identified in 10% to 12% of healthy cats and dogs2,3; however, this finding varies based on which lung ultrasonography protocol is used. Some protocols identify occasional B-lines in up to 50% of healthy cats and dogs, with the number of lines correlated with the amount of lung surface area assessed.4-6 Another common statement is that healthy cats and dogs should not have >3 B-lines per sonographic window, and some sources suggest >2 B-lines per window is abnormal2,7; however, research in clinically healthy cats suggests cats may have incidental B-lines that are coalescing or too numerous to count at a single location when the hemithorax is scanned.4,5

Schematics and corresponding sonograms of the lung surface in dogs. A: A-lines are present in a healthy lung. B: A single B-line (asterisk) is present. B-lines are vertical hyperechoic artifacts that arise from the pleural line, move in sync with the lung surface, extend to the far field of the image, and typically obliterate A-lines (if present). B-lines occur naturally in healthy animals due to microatelectasis and presence of interlobar septa. C: An increased number of B-lines (asterisks) is present secondary to decreased aerated lung (increased lung density) due to congestive heart failure. B-lines can increase in number due to any process that decreases lung aeration, including increased fluid in the lung, increased cell content in the lung, and atelectasis. RS, rib shadow; P-line, pleural line

Reaching consensus regarding POCUS in veterinary medicine is challenging because of lack of clinical research on normal findings in cats and dogs, lack of clear reference intervals for specific POCUS protocols, and small case enrollment in many studies. Early studies of abdominal and thoracic focused assessment with sonography for trauma suggested patients should be placed in lateral recumbency (particularly right lateral recumbency) for examination, but subsequent literature suggested patients should be scanned in the position in which they are most comfortable.8,9 Consensus on ideal positioning, or whether positioning should be adjusted to identify certain pathologies, is lacking. Despite differences in pathology localization (eg, air rises, fluid falls) among positions, many protocols are applied in the same manner regardless of patient positioning, which can lead to false-negative findings. Additional evidence-based research is needed.

3. Limited Training Opportunities & Quality Assurance for Training Curriculum

Quality assurance, standardization, and availability of POCUS-specific training are limited in veterinary medicine compared with human medicine. A survey found lack of adequate training and/or experience is a key barrier to POCUS use in veterinary medicine.10

Many human and veterinary POCUS education programs focus on short-term learning (2- to 4-day courses), often in association with specialized residency training programs11-13; however, long-term learning that incorporates serial repetition is recommended for human critical care ultrasonography.11,12 Combination of an initial course with a long-term program, as well as comparative discussions among institutions and instructors about veterinary curricula and POCUS training courses, can promote standardized learning.

The number of human medicine resident specialty training programs that receive formal training in POCUS has been identified,14-16 but no surveys or data document the number of curricular programs, internship or residency training programs, or postgraduate training programs in veterinary medicine.

4. Factors That Affect Operator Success

Lack of understanding exists regarding ultrasound physics, probe type, machine settings, and how these factors can create artifacts, impact image acquisition, and alter image quality (Video 2). For example, a study in human medicine demonstrated that ultrasound machine presets heavily impact the visibility and characteristics of B-lines.17 Simple machine function alterations (eg, turning off artifact filters when using a linear probe, changing the frequency on a microconvex probe) can also significantly change the appearance of B-lines in humans.18 Some operators choose a single preset (eg, abdominal) based on personal experience for all POCUS assessments without altering machine function, which can impact image quality and interpretation of findings, particularly for lung POCUS. Many aspects of POCUS require specific probe manipulation and a change in machine settings to optimize image interpretation (eg, decreasing depth to assess lung sliding), but these specifications have not been well studied or described and therefore may not be well known.1,10

VIDEO 2 Lung and pleural space POCUS in a dog demonstrates how the pleural line can change at different depth settings (5 cm, A; 8 cm, B; 14 cm, C). Identifying lung sliding is generally easier when the depth setting is minimized and the pleural line is thicker. The focus should be set at or just beyond the pleural line. Changes in depth setting are easy to notice; operators may be unaware of changes that occur with adjustments in less familiar settings (eg, frequency, gain, artifact filters). Labeled still images from the video are available below.

5. Confirmation Bias & Other Errors

Confirmation bias is the act of searching for information that supports a personal belief while ignoring information or findings that contradict the belief.19 For example, history of elective ovariohysterectomy 6 days prior may be overlooked if free abdominal gas is identified on POCUS in a patient presented for acute abdomen, vomiting, and tachycardia (Video 3). Although free gas is normally present in the abdomen for up to 2 weeks following exploratory laparotomy, this may be ignored due to the belief the abdomen is septic. As another example, a benign hepatic nodule unrelated to the spleen may be interpreted as hemangiosarcoma in a dog with hemoabdomen if splenic hemangiosarcoma is believed to be the most likely differential diagnosis, despite lack of evidence of a splenic mass.

Confirmation bias may be especially problematic for POCUS because examination is performed rapidly at the point of care using binary questions that support the hypothesis. In contrast, formal consultative ultrasonography is typically performed by a highly trained sonographer who scans all planes of organs with an open-ended list of differentials and conveys findings to the attending clinician for clinical integration.

Conclusion

POCUS is useful in general practice but has limitations that are important to acknowledge and research to minimize errors. Because POCUS relies heavily on operator skill and knowledge, recognition of personal limitations and documentation of unexpected findings for further consultation are key. Variability in training opportunities and curricula, as well as a lack of understanding of ultrasound physics and machine settings, can compromise image quality and interpretation. Confirmation bias also poses a significant risk. Addressing these limitations and biases is essential for enhancing the accuracy and efficacy of POCUS.

For a review of the top benefits of POCUS in general practice, see the accompanying article.

Listen to the Podcast

Dr. Boysen joined the podcast to highlight the pros and cons of adopting this modality in general practice.