Step-by-Step: Urethral Deobstruction in Cats

Edward Cooper, VMD, MS, DACVECC, The Ohio State University

Urethral obstruction is a potentially life-threatening manifestation of feline lower urinary tract disease that requires immediate medical intervention. Following are recommendations and guidelines for urethral deobstruction in cats, with an emphasis on the importance of minimizing urethral trauma because tearing or stricture formation can increase patient morbidity and mortality and add to treatment costs.1

Do you know who can deobstruct cats in your state? Explore legal considerations for veterinary technicians performing deobstruction.

Anesthesia Protocol

A protocol for managing urethral obstruction without the use of a urethral catheter (as an alternative to euthanasia) has been described in the literature,2 but management of urethral obstruction through placement of a urethral catheter is still the standard of care.

Initial stabilization includes placement of an IV catheter and initiation of fluid therapy. To optimize urethral catheter placement and minimize damage to the urethra, administer analgesia and sedation or anesthesia. For unstable patients (ie, those with electrolyte abnormalities and/or respiratory or cardiovascular compromise), administration of only light sedation should be sufficient. Patients with stable vital signs may receive higher sedative doses or be placed under general anesthesia. All patients should receive pain medication. A novel method of pain control using a coccygeal epidural block may also be beneficial in these patients and can be considered.3

Anesthesia Protocols for Urethral Deobstruction*

Patients with normal mentation & physical parameters

Premedication/sedation/analgesia

Option 1: Ketamine (5-10 mg/kg IV or IM) + diazepam or midazolam (0.25-0.5 mg/kg IV or IM)

Option 2: Buprenorphine (0.01-0.02 mg/kg IV or IM) + acepromazine (0.03-0.05 mg/kg IV or IM) or diazepam/midazolam (0.25-0.5 mg/kg IV or IM)

Coccygeal epidural3

Lidocaine 2% (0.1-0.2 mL/kg)

Induction

Propofol (1-4 mg/kg IV, to effect)

Maintenance

Inhalant anesthesia (eg, isoflurane, sevoflurane)

Patients with electrolyte abnormalities and/or cardiovascular or cardiorespiratory compromise

Sedation/analgesia only

Option 1: Buprenorphine (0.01-0.02 mg/kg IV or IM) + diazepam or midazolam (0.25-0.5 mg/kg IV or IM)

Option 2: Methadone (0.2-0.25 mg/kg IV or IM) + diazepam or midazolam (0.25-0.5 mg/kg IV or IM)

Coccygeal epidural3

Lidocaine 2% (0.1-0.2 mL/kg) administered into the sacrococcygeal epidural space

*Protocols preferred by the author

Vocalization or movement during catheterization indicates insufficient sedation and is more likely to be associated with significant urethral spasm and increased risk for urethral trauma. In these patients, administer higher doses of medications or provide additional analgesics and/or sedatives. Less experienced clinicians may prefer using general anesthesia because it provides longer sedation than injectable medications, allowing more time to complete the procedure. Whether using sedation or anesthesia with intubation, the patient should be monitored (eg, ECG, blood pressure, pulse oximetry) commensurate with clinical status/instability and standard of care.

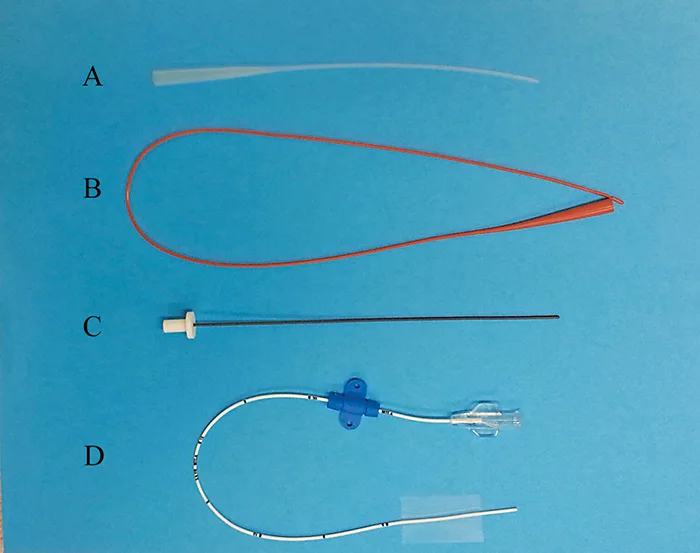

Urinary catheters may be made of polypropylene (A), polyvinyl (B), polytetrafluoroethylene (C), and polyurethane (D). Polyvinyl catheters are not open-ended and therefore not typically used for unblocking but can be placed long-term. Polypropylene catheters are not suitable for longterm placement because of their potential to irritate.

Photos courtesy of Edward Cooper, VMD, MS, DACVECC

Catheter Type & Size

An open-ended catheter made of polypropylene, polytetrafluoroethylene, or polyurethane is typically used to relieve the obstruction. (See Figure 1.) Polypropylene catheters are the most rigid, which may make them more effective in relieving an obstruction; however, they are more likely to cause urethral trauma, especially if excessive force is used during placement. Because polypropylene catheters can also be more reactive and irritating,4 they should not be left in place for ongoing management.

Polytetrafluoroethylene and polyurethane catheters are firmer at room temperature, which facilitates initial unblocking efforts, and they soften when warmed to body temperature, which allows them to be left in place. Placing one catheter that can be used both for deobstruction and ongoing management may cause less urethral trauma.

Consider catheter size when selecting the type of catheter for deobstruction. One retrospective study found that patients unblocked with a 5Fr catheter compared with a 3.5Fr catheter had increased risk for reobstruction within 24 hours (19% vs 6.7%, respectively), which suggested a benefit in using a smaller catheter; however, the potential for confounding factors to have affected the results is significant.5 Another study failed to find an association with catheter size and risk for reobstruction.6 These results suggest the impact of catheter size is unclear.

Preparation

Make sure different types and sizes of catheters are readily available before starting deobstruction. Ideally, start with the smallest and most flexible catheter. Determine the length of the catheter needed to reach the urinary bladder by measuring from the penis to the level of the fourth mammary gland.

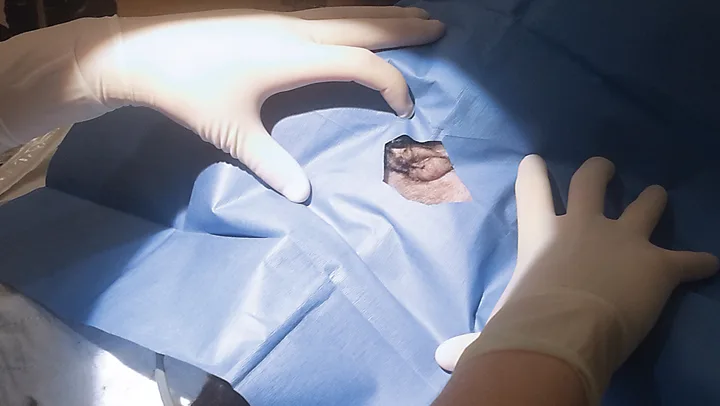

Placing a sterile drape over the perineal region helps reduce the risk for contamination during catheter placement. This patient is in dorsal recumbency.

Following sedation and anesthetization, place the patient in lateral, dorsal, or ventral recumbency, depending on veterinarian preference. Clip the perineal region, prepare the region using aseptic technique, and apply a sterile drape with an opening over the perineum to minimize risk for contamination. (See Figure 2.)

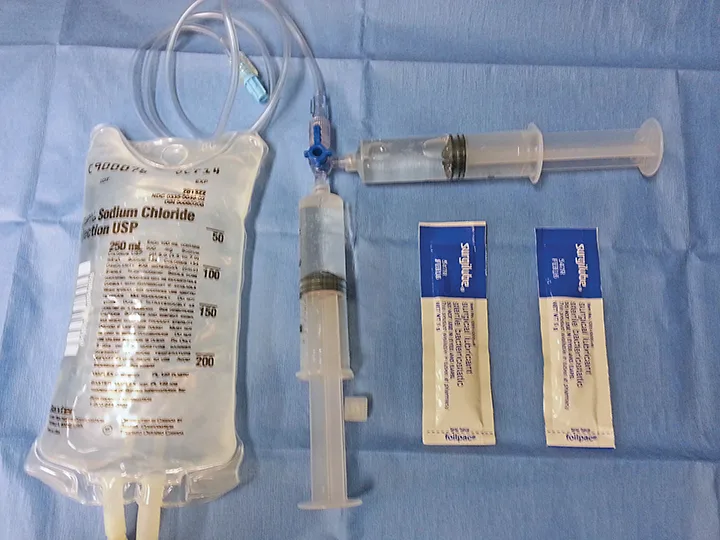

1 ml to 2 ml of sterile lube is placed into a 20 mL syringe, which is then connected to a 3-way stopcock. Another syringe with 10 ml to 20 ml sterile saline is also connected and the 2 syringes are mixed across the 3-way stopcock to create the lubricated flush. Extension tubing can then be used to connect to the urinary catheter to allow flexibility.

Assemble a flushing system to allow hydropulsion and urethral dilation during catheter placement. Mixing sterile saline and sterile lubricant (10:1) using 2 syringes across a 3-way stopcock (see Figure 3) will allow lubricant to be deposited along the entire length of the urethra during flushing, which may help decrease urethral trauma.

Catheterization

Wear sterile gloves during catheter placement. The team member placing the catheter or the assistant can extrude the penis by using pressure on either side, or above and below, and pushing cranially and dorsally. Once the penis is exposed, inspect the tip for a plug or debris and gently massage the tip to remove any lodged material.

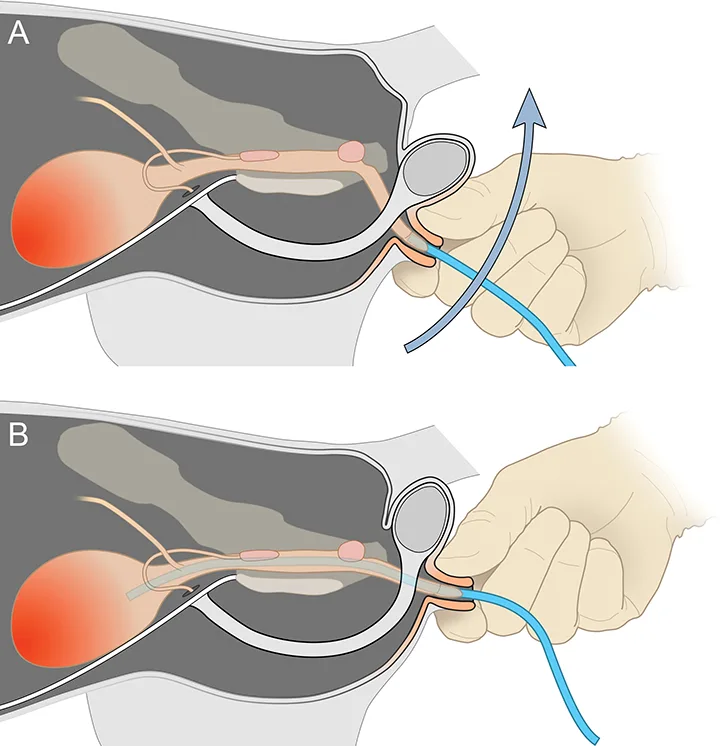

This schematic displays a useful technique for facilitating deobstruction and passage of the catheter. After inserting the tip of the catheter in the penile urethra, the prepuce is pinched and pulled caudally or caudodorsally to straighten the urethra.

Illustration by Tim Vojt. With permission, The Ohio State University

Introduce the lubricated catheter tip into the penile urethra. Maintain gentle cranial pressure on the catheter and grasp and retract the prepuce caudally or caudodorsally to straighten the urethra, which will make it easier to place the catheter and cause less trauma. (See Figure 4.) Gently advance the catheter using minimal force while hydropulsing the lubricated flush. If an obstruction is encountered, use a soft, rapid, back-and-forth (ie, chipping) motion while aggressively flushing until the catheter reaches the bladder. Gentle back-and-forth rotation of the catheter against the obstruction may also be helpful. Do not force the catheter past an obstruction. Stop if repeated efforts to clear the obstruction are unsuccessful or the veterinarian is concerned about a urethral tear.

Referral to a specialty practice that can perform more advanced catheterization techniques may be required. In these circumstances, consider performing a decompressive cystocentesis until other interventions can be performed.

Once the catheter has been placed successfully, empty and flush the urinary bladder until the effluent is relatively clear of blood and gross debris. If a polypropylene catheter was used for deobstruction, replace it with a softer, indwelling catheter that should then be secured appropriately based on the type of catheter. Confirm appropriate catheter placement using abdominal radiography or ultrasonography and visualization of urine flow through the catheter. Imaging will also help identify bladder stones and free abdominal fluid. Connect the catheter to a closed sterile collection system to facilitate monitoring of urine production and decrease the risk for ascending infection, which is more likely to occur with an open system.7

Always wear gloves when handling the closed collection system, which should not be placed on a bare floor. An Elizabethan collar will prevent the patient from dislodging the catheter.

Some clinicians mandate the catheter remain in place for a minimal period to allow resolution of inflammation and clearing of debris, clots, and/or crystals. However, a urinary catheter can irritate the urethral epithelium and potentially contribute to lower urinary tract inflammation.4 Length of catheterization should be based on clinical criteria (eg, resolution of biochemical abnormalities and postobstructive diuresis [if present], gross character of the urine [clear vs gritty vs hemorrhagic]). As reobstruction may occur, the patient should be monitored for some time after the catheter has been removed. Before discharge, the patient should pass urine on at least one to 2 occasions and the bladder should be normal size.

Conclusion

Treatment of urethral obstruction often requires placement of a urinary catheter to restore urethral patency. Several catheter types and sizes are available; the appropriate catheter should be selected based on the patient's needs. Sedation and analgesia should be administered to all patients to provide pain relief and relaxation and help minimize urethral trauma during deobstruction. Patients with stable vital signs can receive general anesthesia. Because reobstruction may occur, patients should be monitored to ensure they have normal urinary function before discharge.