Update, Diagnosis, & Treatment of Feline Asthma

Laura A. Nafe, DVM, MS, DACVIM (SAIM), University of Missouri

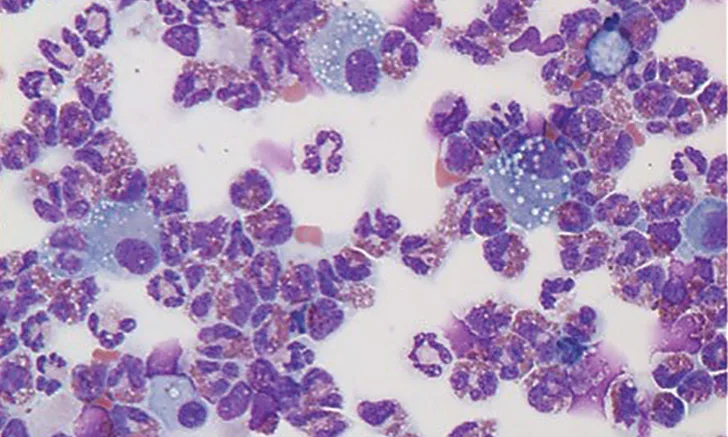

Figure 1 Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cytology from a cat. Note the predominance of eosinophils, which is characteristic of feline asthma. Figure courtesy of Carol Reinero, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, University of Missouri

Asthma is a common cause of feline lower airway disease that results in coughing and/or intermittent respiratory distress in most patients. Feline asthma is a Type-1 hypersensitivity reaction to specific aeroallergens.1 The combination of asthma’s hallmark clinical features (ie, eosinophilic airway inflammation, bronchoconstriction, excessive mucus production, airway edema) results in an expiratory respiratory pattern, characterized by prolonged expiratory time and an abdominal push during exhalation. Long-term, these patients can develop irreversible airway remodeling secondary to chronic airway inflammation.

Feline asthma most commonly affects young to middle-aged cats. Clinical presentation varies with some cats having only one clinical sign—a chronic cough or dyspnea (ie, status asthmaticus)2—whereas others may have both a chronic cough and intermittent exacerbations causing expiratory distress.3

Absence of a cough does not rule out asthma because some cats may have respiratory distress as the only presenting complaint. Definitive diagnosis requires imaging and airway sampling combined with ruling out other causes of airway eosinophilia (eg, pulmonary parasites, heartworm-associated respiratory disease). Treatment is aimed at controlling airway inflammation and preventing and/or reducing respiratory distress episodes with bronchodilator therapy.

Related ArticlesHeartworm Infection at a GlanceTop 5 Clinical Differences Between Cats & DogsHandling Feline Patients: Less is Always More

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of feline asthma can be challenging because the disease’s clinical features may overlap with chronic bronchitis, heartworm-associated respiratory disease, or other pulmonary conditions. Diagnosis is achieved with a combination of consistent clinical signs (ie, cough and/or respiratory distress), physical examination, thoracic radiography, and eosinophilic inflammation on airway cytology. (See Figure 1.)

Physical examination may be normal or reveal increased bronchovesicular sounds, tachypnea, and/or expiratory wheezes.

Classic thoracic radiographic findings in patients with feline asthma include a diffuse bronchial or bronchointerstitial pattern, hyperinflation, and/or collapse of the right middle lung lobe caused by mucus plug obstruction.3,4 (See Figure 2.) Up to 23% of asthmatic cats have normal thoracic radiographs.5

Eosinophilic airway inflammation is characteristic of asthma, but veterinarians should keep in mind that other disease conditions can result in similar clinical scenarios and eosinophil recruitment. All cats suspected of having feline asthma should have a heartworm antigen and antibody test and fecal evaluation for other parasitic diseases.

Thoracic radiograph of a cat with asthma showing a diffuse bronchial pattern and collapse of the right middle lung lobe. Figure courtesy of Oklahoma State University Center for Veterinary Health Sciences

Management

Management of feline asthma can be separated into acute and chronic treatment strategies.

Acute

Acute management is aimed at stabilizing the patient in respiratory distress. Stabilization of the status asthmaticus patient includes minimizing stress (eg, sedation), providing supplemental oxygen, and bronchodilator therapy (eg, inhaled albuterol via metered dose inhaler, nebulization, injectable terbutaline). (See Figure 3.) Identifying an expiratory respiratory pattern can guide the veterinarian to any bronchoconstriction, resulting in early intervention with bronchodilator therapy. The author prefers injectable terbutaline for acute management because relying on appropriate delivery of an inhaled medication in a dyspneic patient can be challenging. Glucocorticoids are important in asthma management to reduce airway inflammation and can be used in an acute setting, but veterinarians should remember that the anti-inflammatory effects take 48 to 72 hours to be fully efficacious. As such, if an asthma diagnosis is highly suspected in a cat with acute respiratory distress, steroids should be initiated as quickly as possible.

Medication administration via a metered dose inhaler using a feline-specific spacer chamber (AeroKat Feline Aerosol Chamber, Trudell Medical International, Ontario, Canada; aerokat.com). Figure courtesy of Laura A. Nafe, DVM, MS, DACVIM (SAIM), and AeroKat

Chronic

Chronic management of feline asthma is aimed at reducing airway inflammation and preventing and/or reducing bronchoconstriction, if applicable.

Reducing inflammation is best achieved by minimizing exposure to aeroallergens and environmental irritants (eg, dust, aerosols) combined with an oral glucocorticoid (eg, prednisolone). Many patients can be transitioned to inhaled steroid therapy (eg, fluticasone) to minimize systemic side effects long-term.6

Bronchodilator therapy is not recommended unless bronchoconstriction is a component of the clinical scenario, manifested as respiratory distress. Some feline asthma patients exhibit only signs of cough and have no respiratory distress, and bronchodilator therapy is neither needed nor recommended in these cases. Though bronchodilator therapy is fairly safe, it is another oral medication for clients to administer daily that can adversely affect the cardiovascular system in at-risk patients.

Out of concern for the S-enantiomer’s proinflammatory effects, racemic albuterol should be avoided in patients requiring chronic management of bronchoconstriction.7 Oral terbutaline or theophylline are preferred for chronic bronchodilatory therapy. Novel therapeutics used as monotherapy for management of experimental asthma management (eg, cyproheptadine, cetirizine, nebulized lidocaine, maropitant) are ineffective.8-10 Immunotherapy and mesenchymal stem cell therapy have shown promise as future novel therapeutics.11,12

Conclusion

Feline asthma is a common cause of cough and intermittent respiratory distress in cats that can be challenging to diagnose and treat. However, prognosis is generally good with the appropriate treatment. Veterinarians should suspect feline asthma in young to middle-aged cats presenting for cough and/or respiratory distress and understand that not all asthmatic cats have both cough and dyspnea. Important differential diagnoses that can be challenging to differentiate clinically and radiographically include chronic bronchitis, heartworm-associated respiratory disease, and pulmonary parasites; this emphasizes the importance of pursuing additional diagnostics (eg, heartworm testing, airway wash) when possible. Treatment is aimed at reducing aeroallergen exposure, reducing airway inflammation, and managing bronchoconstriction in cases that have concurrent expiratory respiratory distress.