This response is correct!

Tritrichomonas foetus Infection in Cats

Emily Nissa Gould, DVM, MS, DACVIM (SAIM), Texas A&M University

M. Katherine Tolbert, DVM, PhD, DACVIM (SAIM), Texas A&M University

Tritrichomonas foetus, a protozoal parasite that infects the distal ileum and colon of cats, should be on the differential list for any cat with large- or mixed-bowel diarrhea, especially in patients failing to respond to empirical therapy for Giardia spp.1,2

The route of transmission is presumed to be fecal–oral in nature.3,4 T foetus is not considered to be an important canine pathogen and is rarely the primary cause of diarrhea in dogs.5-7 To the authors’ knowledge, there have been no reported cases of transmission to humans or direct transmission from a cat to a dog.

Clinical Signs

The most common clinical sign of T foetus infection is chronic, recurrent diarrhea of large-bowel origin characterized by hematochezia, tenesmus, and mucus. Cats may also be presented with mixed-bowel diarrhea.1 T foetus should be on the differential list for any cat with large- or mixed-bowel diarrhea, especially in patients failing to respond to empirical therapy for Giardia spp.1

Diagnosis

T foetus may be diagnosed by visualization of the organism on a direct fecal smear or via fecal culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). For fecal smear or culture, a freshly voided diarrheic fecal sample may be used (ideally within minutes of collection, as further delay may decrease assay sensitivity). When possible, a fresh sample can also be directly collected via fecal loop or, optimally, via colonic flush. The sample should be free of cat litter and should not be refrigerated.

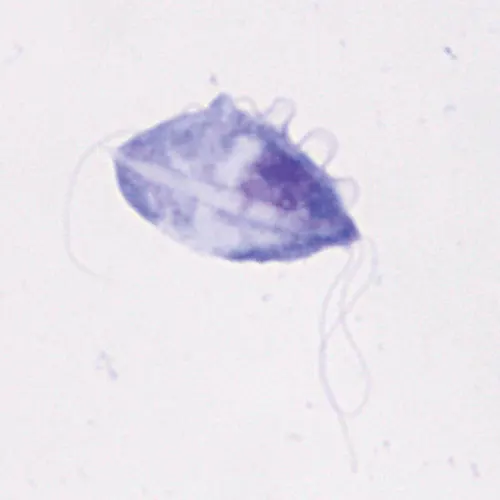

Microscopic image of a single feline T foetus organism (100× objective). Characteristic features of T foetus—including a dorsal undulating membrane, 3 anterior flagella, and a posterior flagellum—can be observed.

Although T foetus may be visible on direct fecal smear (Figure 1), the sensitivity of this technique is low (14%),2 which can result in false negatives. In addition, T foetus can microscopically resemble other motile, flagellated GI pathogens such as Giardia spp, which can lead to misdiagnosis. However, the motility pattern of Giardia spp (ie, falling-leaf–like) is distinct from that of trichomonads (ie, erratic yet forwardly progressive movement).

PCR testing is considered the gold standard for diagnosing T foetus infection, with excellent sensitivity (70%) and specificity (100%),8 and is the preferred diagnostic test; however, if PCR testing is cost prohibitive or unavailable, fecal culture using the InPouch TF Feline test (BioMed Diagnostics) can be conducted. This test is less expensive, albeit much less sensitive, than PCR (55%) and not 100% specific9; however, it can be performed in-house. No single test has 100% sensitivity; therefore, retesting is recommended with any of these tests if the result is negative yet signalment and clinical signs are strongly suggestive of T foetus infection.

Video of T foetus & Giardia spp

For a video of T foetus and Giardia spp motility patterns, visit JodyGookin.com and select the T foetus Resources tab.

Treatment & Prognosis

No available or approved therapeutic completely eradicates T foetus infection. Once-daily oral administration of the antiprotozoal ronidazole (30 mg/kg PO q24h for 14 days) is recommended, as twice-daily dosing can increase the risk for neurotoxicity.10 Neurotoxicity may be reversible; however, if lethargy or neurologic signs develop, the drug should be discontinued immediately and not used again in the patient. Although ronidazole may resolve clinical signs in some cats, many cats may remain subclinically infected or fail to improve clinically.10 Metronidazole is not effective in clearing infection and is not recommended for treatment of T foetus infection.11,12

Cats in high-density housing environments (eg, shelters, catteries, cat shows) have an increased risk for contracting T foetus infection.2 There is not, however, an increased risk for infection in sharing food or water bowls for cats not living in a high-density housing environment.2 No disinfection measures have been shown to be effective beyond increasing the number of square feet per animal in facilities housing large numbers of cats.2 Long-term outcome for cats with chronic trichomoniasis is good. Clinical signs generally resolve in most cats within 22 to 24 months; however, cats may be subclinical carriers and have periods of relapse of clinical signs during stressful events.13

Global Commentary

Andrew Sparkes, BVetMed, PhD, DECVIM, MRCVS, International Cat Care, Wiltshire, United Kingdom

Tritrichomonas foetus appears to have a worldwide distribution. Published studies have documented feline infections in many countries, including Australia,1,2 Austria,3,4 Brazil,5 Canada,6,7 France,8 Germany,9,10 Greece,11 Hong Kong,12 Italy,13,14 Japan,15 Korea,16,17 the Netherlands,18 Norway,19 New Zealand,20 Poland,21 Spain,22,23 Switzerland,24,25 the United Kingdom,26,27 and the United States.28–30

Such widespread reports of occurrence, as well as its associated clinical disease, emphasize the importance of considering T foetus as a potential cause feline large bowel diarrhea anywhere in the world. Isolates of T foetus from cats appear genetically distinct from T foetus isolates from cattle, which appear to be identical to Trypanosoma suis from pigs). The name of the organism in cats perhaps ought to be changed to Tritrichomonas blagburni, but whether natural transmission between species can occur is not clear.31

As the authors of this article point out, PCR is by far the most sensitive diagnostic test for T foetus infection in cats; however, cost and availability may limit the use of this test in some situations. Wet (ie, saline) microscopic preparations of fresh diarrheic feces, colonic washes, and InPouch fecal cultures are alternatives that are less sensitive than PCR but may more readily detect infection in clinically affected cats as compared with subclinically affected cats.31 Repeat testing of cats is likely to increase the sensitivity of these tests.

Studies suggest that around two-thirds of cats are likely to show good improvement or resolution of clinical signs with 14 days of ronidazole therapy at 30 mg/kg q24h30,31 and that neurologic adverse events may develop in up to 4% to 5% of cats.30 It is recommended that only cats with confirmed infections be treated with ronidazole.

If ronidazole is unavailable, the more widely available tinidazole may be an option. Some clinical efficacy has been reported with tinidazole at 30 mg/kg q24h for 14 days,32,33 although efficacy is lower than with ronidazole. In untreated cats, approximately 90% are likely to show resolution of clinical signs within 2 years,34 although subclinical infection may still be present.

PCR = polymerase chain reaction