Treatment of Canine Primary Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia

DefinitionPrimary IMHA is caused by an autoantibody directed against an epitope on the red blood cell membrane. Unlike secondary IMHA-which is caused by formation of antibodies induced by microorganisms, drugs, or previous transfusions-the event that results in formation of antibodies is unknown in primary IMHA.

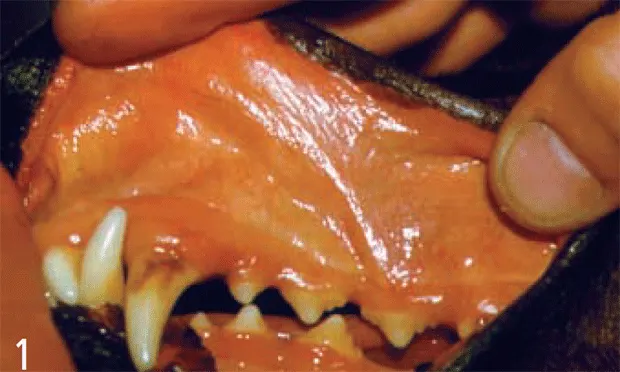

Figure 1 (above). Icteric mucous membranes in a dog with severe immune-mediated hemolytic anemia

SystemsAlthough the primary body system affected is the erythron, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia can occur concurrently (Evans's syndrome). In addition to the hematopoietic system, other body systems are affected by such sequelae as pulmonary thromboembolism, systemic thromboembolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic dysfunction, and gastric ulceration and hemorrhage.

Incidence/Prevalence/Geographic DistributionIMHA occurs worldwide. Neither the incidence nor the prevalence has been determined. An increase in cases during the summer as been reported.1,2

SignalmentBreed Predilection. Many breeds of dogs have been reported to be predisposed. The strongest evidence for a breed predilection is in cocker spaniels, which have been implicated in several studies.1-7 Other breeds include English springer spaniels, collies, poodles, and miniature schnauzers.

Age and Range. Dogs are diagnosed from 1 to 13 years, with a median of 6 years.

Gender. Intact and spayed females are overrepresented.

Causes/Risk FactorsSeveral studies have attempted to identify a link between vaccination and IMHA. Only one study has found an increase in vaccinated dogs.8 The absence of dog erythrocyte antigen 7 in cocker spaniels has been shown to be a risk factor for IMHA.3

PathophysiologyA type II hypersensitivity reaction mediates destruction of red blood cells in IMHA.9 Antibodies specific for a component of the red blood cell membrane binds to red blood cells. Destruction of these cells occurs in the spleen (extravascular) or, following complement fixation, hemolysis occurs intravascularly. Antibodies may be directed at red blood cell precursors, resulting in a nonregenerative variant of IMHA.10 Antibodies are from either the IgG or the IgM class.

SignsVague and usually referable to acute anemia, including acute onset of depression, anorexia, weakness, and lethargy. Owners may report discolored urine.

HistoryIngestion of acetaminophen and onions and administration of vitamin K may cause hemolytic anemia. Obtain a careful history to identify these causes and treat them appropriately.

Physical ExaminationPale, often icteric mucous membranes (Figure 1). Pigmenturia from either hemoglobinurina or bilirubinurina. In severe cases, tachycardia and a heart murmur may be found; palpation reveals hyperdynamic pulses. Abdominal palpation identifies hepatomegaly or splenomegaly in 40% of cases.6 Petechiae appear if concurrent immune-mediated thrombocytopenia is present. Occasionally, lympha-denopathy is present.

Pain IndexPain is not a prominent feature.

Diagnosis

Not typically made on the basis of history or physical examination findings. A minimum database is obtained during evaluation of an acutely ill dog, the results of which indicate anemia resulting from a hemolytic process. Identifying a hemolytic disorder and eliminating causes of secondary IMHA make the definitive diagnosis of IMHA. Several disease processes can cause hemolytic anemia in dogs, such as zinc toxicosis; infectious diseases, such as ehrlichiosis, mycoplasmosis (hemobartonellosis), babesiosis, and bartonellosis; neoplasia (hemangiosarcoma or lymphoma); and drug or onion toxicity. Because of this wide range of differential diagnoses and the array of diagnostic tests needed to rule them out, diagnosis is not covered in this article.

Postmortem FindingsThe prominent feature is macro- and microthrombi coupled with systemic fibrin deposition.11 Pulmonary thromboemboli are commonly associated with acute death. Thrombi are also seen in abdominal organs; in one study, the spleen was the most commonly affected organ.1

Tissue necrosis and infarction, which result from a lack of blood flow, are other postmortem findings. Infarction, which occurs after formation of an embolus, frequently occurs in the spleen, heart, and kidneys. Necrosis occurs independent of embolism and is postulated to result from anemia-induced hypoxia, as evidenced by centrolobular necrosis in the liver.

Complications of therapy are often identified during necropsy. Secondary infections, such as pneumonia or pyelonephritis, occur as a result of immunosuppressive therapy. Gastric erosions and gastric ulcers have been described as a sequela to prednisone therapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Gastric erosions seen on necropsy in a dog treated with prednisone. The dog died of sepsis.

Treatment

Inpatient or OutpatientBecause the published studies of treatment of dogs with IMHA originate from teaching hospitals, bias toward inclusion of sicker dogs and management of dogs with IMHA as inpatients is likely. Consequently, reported cases are managed as inpatients and the average hospital stay is 6 days.1,5,6

Transfusion Therapy

Most dogs with IMHA receive packed red blood cell transfusions as a treatment for anemia (Figure 3). Those who have comorbid disseminated intravascular coagulation, with prolonged prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times, should also receive fresh frozen plasma. Routine transfusion of fresh frozen plasma is not recommended because it does not prevent pulmonary thromboembolism. Theoretically, providing increased oxygen-carrying capacity with a hemoglobin solution lacking the antigenic red blood cell membrane of intact red blood cells should provide a treatment advantage, although one study showed the opposite effect.12 However, because of this study's retrospective design, its results cannot be considered to provide definitive evidence against the use of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers in IMHA.

Figure 3. Blood transfusions are an aspect of treatment in most dogs with immunemediated hemolytic anemia.

ActivityActivity restriction is unnecessary-the critical nature of the illness often prevents ambulation.

Drug Therapy

Antibiotic TherapyAdminister doxycycline while the results of infectious disease tests are pending. In dogs with secondary infections from immunosuppressive agents, the type of infection or culture results will dictate antibiotic choice.

Immunosuppressive AgentsPrednisone is considered first-line therapy, although its use has not been evaluated in a clinical trial. The benefit of adding other immunosuppressive agents to prednisone therapy is unclear because the data are conflicting. The information on the outcome of treatment with azathioprine is mixed, despite its having been recommended for treatment of IMHA for decades. All studies of azathioprine use are retrospective. One study showed no survival advantage in dogs given azathioprine in addition to prednisone12 and 3 showed a survival advantage.1,4,6 Because the dogs were not randomly assigned to the various treatment groups, selection bias is likely, as the dogs treated with azathioprine may have had a better prognosis than those not treated with azathioprine. Mounting retrospective and prospective data suggest that cyclophosphamide administration does not benefit dogs with IMHA.5,7,12 Evidence from three retrospective studies suggests that IV immunoglobulin may be effective in controlling hemolysis on a short-term basis, but as with azathioprine, a randomized, controlled trial must be done to confirm this interpretation of the available evidence.12-14 Currently, few data are available on the outcome of dogs given cyclosporine.

Anticoagulant TherapyThe anticoagulant effects of unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, and aspirin have been studied in dogs. To date, no dose of heparin has been shown to prevent thromboembolic disease.1,5 An ultralow dose of aspirin (0.5 mg/kg daily) was associated with improved survival, but its effect on rates of thromboembolism were not reported.1

Follow-up

Client EducationClients must be made aware of the high mortality rate and the possibility of sudden death from pulmonary thromboembolism.

Patient MonitoringDogs released from the hospital should be examined once a week until the CBC indicates consistent improvement or stabilization of hematologic values. Owners should monitor the pet for lethargy or discolored urine, which may indicate relapse. Dogs maintained on long-term prednisone therapy or any other immunosuppressive agents should have urine obtained for culture every 3 months to identify subclinical urinary tract infections.

Long-Term ManagementBecause of the side effects from immunosuppressive drugs, they should be tapered gradually over approximately 12 months after control of hemolysis. However, relapse is common and can occur after therapy has been stopped or even while the patient is still receiving immunosuppressive drugs. Prednisone is typically administered at a dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg twice daily. Once hemolysis ceases, the dose is decreased by approximately 25% every 2 to 6 weeks until a dose of 0.5 mg/kg every other day is achieved. The dog should be maintained at this dose for 6 or more months. Tapering the dose of azathioprine is often done after the dose of prednisone reaches an every-other-day regimen.

In General

Relative CostHospitalization at an average stay of 6 days may cost as much as $5000 because of the need for 24-hour-a-day ICU care, laboratory testing to rule out causes of secondary IMHA, and multiple transfusions.

PrognosisThe rate of death is highest in the first two weeks after diagnosis. Laboratory factors associated with a poor prognosis include elevated bilirubin levels, low packed cell volume, and low reticulocyte count. One year after diagnosis, approximately 50% of dogs are still alive.2,4,6 Dogs may die acutely from pulmonary thromboembolism even if the anemia has resolved with immunosuppressive therapy.

Future ConsiderationsIdentification of the optimal protocol to prevent pulmonary thromboembolism is essential to improving outcome.

TREATMENT OF CANINE PRIMARY IMMUNE-MEDIATED HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA • Ann E. Hohenhaus

References

Evaluation of prognostic factors, survival rates, and treatment protocols for immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs: 151 cases (1993-2002). Weinkle TK, Center SA, Randolph JF, et al. JAVMA 226:1869-1880, 2005.

Idiopathic immune mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs: 42 cases (1986-1990). Klag AR, Giger U, Shofer FS. JAVMA 202:783-788, 1993.3. Case-control study of blood type, breed, sex and bacteremia in dogs with immune mediated hemolytic anemia. Miller SA, Hohenhaus AE, Hale AS. JAVMA 224:232-235, 2004.4. Prognostic factors for mortality and thromboembolism in canine immune mediated hemolytic anemia: A retrospective study of 72 dogs. Carr AP, Panciera DL, Kidd L. J Vet Intern Med 16:504-509, 2002.5. Treatment of immune mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs with cyclophosphamide. Burgess K, Moore A, Rand W, et al. J Vet Intern Med 14:456-462, 2000.

Immune mediated hemolytic anemia: 70 cases (1988-1996). Reimer ME, Troy GC, Warnick LD. JAAHA 384-391, 1999.7. Cyclophosphamide exerts no beneficial effect over prednisone alone in the initial treatment of acute immune mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Mason N, Duval D, Shofer FS, et al. J Vet Intern Med 17:206-212, 2003.8. Vaccine associated immune mediated hemolytic anemia in the dog. Duval D, Giger U. J Vet Intern Med 19:290-295, 1996.9. Antigen specificity in canine autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Day MJ. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 69:215-224, 1999.10. Nonregenerative form of immune mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs. Jonas LD, Thrall MA, Weiser MG. JAAHA 23:201-203, 1987.11. Correlation between leukocytosis and necropsy findings in dogs with immune mediated hemolytic anemia: 345 cases (1994-1999). McManus PM, Craig LF. JAVMA 218:1308-1313, 2001.

Influence of drug treatment on survival of dogs with immune mediated hemolytic anemia: 88 cases (1989-1999). Grundy SA, Barton C. JAVMA 218:543-546, 2001.13. Intravenous human immunoglobulin for the treatment of immune mediated hemolytic anemia in 13 dogs. Kellerman DL, Bruyette DS. J Vet Intern Med 11:327-332, 1997.14. Intravenous administration of human immune globulin in dogs with immune mediated hemolytic anemia. Scott-Moncrieff JCR, Reagan WJ, Snyder PW, et al. JAVMA 210:1623-1627, 1997.