Ultrasonography in the primary care veterinary clinic is increasingly affordable, has a positive impact on patient care, and is being used more frequently.1,2 Although accuracy and utility are user-dependent, ultrasonography can facilitate efficient and reliable diagnosis.3

Echogenicity refers to tissue’s ability to reflect or transmit ultrasound waves and is represented by visible differences on the screen. A structure can be classified as anechoic (black on the screen) or, when a comparison is being made, hypoechoic (darker) or hyperechoic (lighter).

Following are the author’s top 5 situations in which ultrasonography is used in the clinic.

1. Urinary Bladder Evaluation & Cystocentesis

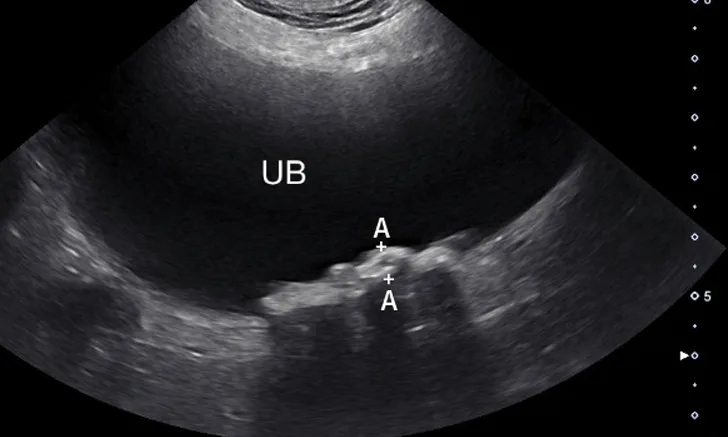

Cystocentesis allows sterile collection of urine while avoiding the potential complications of manual bladder compression, urethral catheterization, or contamination from free-flow collection.4 Ultrasound guidance can help decrease risk of unintentionally inserting the needle into nearby structures (eg, colon, caudal vena cava, descending aorta) and allows for brief assessment of the urinary bladder. Although some pathologic changes in the urinary bladder (eg, mild cystitis) can be subtle and easily overlooked, other diseases can be very apparent. Cystic calculi can range in shape and size but, when large enough, may have a hyperechoic interface that causes a distal acoustic shadow (Figure 1). In patients with hematuria, blood clots with different shapes can float in the urine or rest dependently against the bladder wall. Neoplasia of the urinary bladder can differ in visualized size and echogenicity; however, neoplasia typically originates from the bladder wall, demonstrates irregular margins, and protrudes into the bladder lumen. If a mass is identified in the urinary bladder, cystocentesis is not recommended to prevent potential seeding of neoplastic cells in the soft tissue along the path of the needle.

Sagittal image of the urinary bladder (UB; cranial aspect toward the left side of the image). Numerous calculi (between calipers) are present along the dependent aspect of the urinary bladder (away from the probe with the patient in dorsal recumbency) and, unlike in cases of neoplasia, are hyperechoic and cast a clean acoustic shadow.

2. Identification of Peritoneal, Pleural, & Pericardial Effusion

Patients with cavitary effusion can have a range of clinical signs, many of which are nonspecific because cavitary effusions are sequelae to a variety of disease processes.5 Ultrasonography is useful in the identification and sampling of effusion fluid in cats and dogs and is more sensitive in the detection of smaller volumes than radiography.6 Primary body cavities to evaluate for effusion include the abdomen (peritoneal space), thorax (pleural space), and pericardial space (Figure 2).5

Abdominal effusion (A; asterisk) adjacent to a normal spleen (arrow). Abdominal carcinomatosis with secondary neoplastic effusion was diagnosed. Left parasternal short-axis view of a heart with pericardial (B; asterisks) and pleural effusion (arrow).

The abdomen is most commonly evaluated with the patient in dorsal or lateral recumbency, but scanning the dependent portion with the patient in lateral recumbency can be helpful if only a small amount of effusion is present (see Suggested Reading).6,7 Evaluation for pleural effusion is performed with the patient standing or in ventral recumbency and should begin at the eighth to ninth intercostal space at the level of the costochondral junction. This space is also recommended when thoracocentesis is used in these patients.8 Evaluation for pericardial effusion in the right third to fifth intercostal space at the level of the costochondral junction provides the best acoustic window to the heart.5

Cavitary effusion is normally anechoic on ultrasound but can differ based on fluid type.6 Echogenicity and cytologic classification of effusion is based on cellular and protein content, increasing in echogenicity from pure transudate (anechoic) to modified transudate (variably echoic) and exudate (hyperechoic)6,9; however, the echogenicity of cavitary fluid can vary; thus, fluid analysis is required to confirm the exact nature of the fluid.

3. Abdominal Mass Identification in the Liver & Spleen

Hepatic and splenic nodules or masses can be primary or metastatic; can be benign or malignant; and may appear as a single mass, multiple masses, or diffusely infiltrative.10,11 Operator skill level, resolution of the ultrasound transducer, and echogenicity of the surrounding parenchyma can impact detection of soft-tissue nodules.12 Common malignant hepatic and splenic neoplasms include hepatocellular carcinoma, hemangiosarcoma, lymphoma, and histiocytic sarcoma. Common benign changes in the liver and spleen include hyperplasia, myelolipoma, hematoma, lymphoid hyperplasia, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.12,13 A large hepatic mass and peritoneal effusion are more often associated with neoplasia than a benign growth in the liver.13 In the spleen, nodules 1 to 2 cm in diameter, multiple targetoid lesions (hyperechoic center with hypoechoic rim), and peritoneal effusion are associated with neoplasia.14 Hepatic and splenic masses can have diverse characteristics, including well- or poorly circumscribed margins, variable echogenicity, fluid cavitation, and mineralization (Figure 3).

Transverse image of the right liver in a dog with a hyperechoic and multicavitary liver mass (A; asterisk) adjacent to a normal portion of liver (arrow). Deep (ie, bottom of the image) to the liver and the mass, the diaphragm appears as a hyperechoic line. Hypoechoic mass (B; asterisk) protruding from the splenic capsule.

4. Female Reproductive Evaluation (Pyometra, Dystocia)

The uterus normally appears as a tubular structure between the urinary bladder and colon on ultrasound. In dogs, the uterus can have different thicknesses and echogenicity depending on the stage of the estrus cycle; however, in cats, the uterus is usually not visualized.15 Because uterine horns have small wall thickness, they can lack easily identifiable wall layers, which can be used to help distinguish a uterine horn from a nearby intestinal segment with thicker and more apparent wall layers. (Figure 4).15

Right uterine horn of a dog with pyometra. The uterine wall (arrows) is too thin to be a normal small intestinal segment.

Pyometra is a reproductive emergency that requires rapid diagnosis and treatment.16 In patients with pyometra, the uterus contains variable amounts of echogenic intraluminal fluid, with varying degrees of dilation and wall thickness.16 Ultrasound findings should be considered in conjunction with patient history, physical examination findings, and laboratory results, as other less common differentials (including mucometra, hydrometra, and hemometra) are also possible.16 Distinct wall layering may be lost in small intestinal segments that are severely dilated; this can be similar in appearance to a fluid-dilated uterus.

In pregnant patients, both B-mode and M-mode ultrasound can be used to count fetal heart rate and quickly assess fetal health.17 The normal fetal heart rate in cats and dogs is >220 bpm.18 A fetal heart rate less than double that of the dam can indicate fetal distress, with rates <180 bpm representing severe distress.17,19 Fetal and embryonic death share similar ultrasound signs, including absent heartbeat, echogenic fluid in the gestational chamber, and gas accumulation.15

5. Assessment of Gallbladder Mucoceles

The gallbladder is located just to the right of midline between the quadrate and right lateral liver lobes. A normal gallbladder contains anechoic bile and is thin-walled (cats, 1 mm; dogs, ≤2 mm).10,20 In cats, an occasional bilobed gallbladder is normal.10 Bile is normally anechoic, but variably echogenic sludge can accumulate in the gallbladder as suspended particulates or dependent luminal contents.21 Echogenic luminal contents can sometimes be incidental and not associated with biliary disease.21

Dilation or distension of the gallbladder with accumulated hypoechoic mucus may be classified as a gallbladder mucocele but can also be characterized as inspissated bile, mucinous hyperplasia, cystic hyperplasia, and other associated conditions.21 Gallbladder mucoceles are more common in older, small-breed dogs and are rare in cats.21,22 The formation of gallbladder mucoceles is a continuum, starting with echogenic bile, then a stellate pattern, and finally a kiwifruit pattern (ie, a round accumulation of hypoechoic mucus that contains thin, stellate hyperechoic striations; Figure 5).21 Although the exact etiology of mucoceles is controversial, their clinical importance is important, as they can lead to gallbladder rupture, bile peritonitis, and emergency surgery.21

A mature gallbladder mucocele with a central hyperechoic area that is heterogeneous with linear hyperechoic striations in a dog. This appearance is often described as a kiwifruit pattern.

Elective cholecystectomy (ie, prior to biliary obstruction or gallbladder rupture) has been shown to have a lower mortality rate than nonelective cholecystectomy (ie, after obstruction or rupture).23 Suspended (ie, not gravity-dependent) mucus and/or hyperechoic bile are both potential indications for cholecystectomy.23

Although mature gallbladder mucoceles are associated with gallbladder enlargement and wall thinning, numerous etiologies (eg, cholecystitis, gallbladder wall edema, cholecystolithiasis, cystic mucosal hyperplasia, neoplasia [rare]) can also lead to gallbladder wall thickening (>3-3.5 mm).10,20 Bile aspiration via ultrasound-guided cholecystocentesis can be performed for bile culture and/or gallbladder decompression10; however, this procedure has increased the risk for bile leakage (and secondary peritonitis) with gallbladder distension or disease of the wall.

Conclusion

Ultrasonography can greatly improve the diagnostic capability of a general practice when clinicians have the proper training and experience.