Top 5 Tips for Sedation & Anesthesia in Fractious Dogs

Katherine Bennett, DVM, DACVAA, Veterinary Specialty Center, Buffalo Grove, Illinois

Christine Egger, DVM, MVSc, CVA, CVH, DACVAA, University of Tennessee

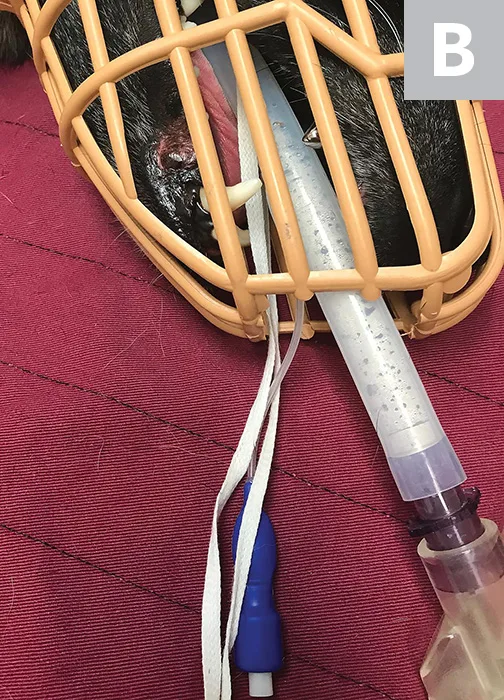

A long extension set directly connected to the catheter, which is placed in the lateral saphenous vein. An injection port is accessible (out of frame).

Aggression represents over 50% of behavior-related problems in dogs,1 and fractious animals pose an inherent risk to veterinary staff. Behavior management is the ideal long-term solution for aggressive or fractious animals; however, some surgical or diagnostic procedures require relatively immediate attention and preclude most recommended behavior modifications. Precautions should be taken to ensure both patient and team safety when sedating or anesthetizing these patients.

Following are the authors’ tips for safe handling of a sedated or anesthetized fractious dog presented for diagnostic or surgical procedures.

1. Owner Communication

Communication with the pet owner ahead of the scheduled appointment is critical. Discussion should include current medications, patient behavior at home, and whether the owner is comfortable medicating the patient at home. Owner involvement can help facilitate a team-based approach to safe and effective patient sedation.2 In addition, a thorough risk assessment should be explained to the owner, as many sedative medications can have adverse effects on patients with underlying diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease. Patients with underlying systemic disease may require dose alterations and/or alternative drug protocols to account for comorbidities.

2. Preappointment Preparation

At-home administration of one or more sedatives (eg, trazodone, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, acepromazine, alprazolam; Table 1) the day before and the day of the scheduled visit allows for multimodal anxiolysis and can facilitate delivery of additional sedatives in the clinical setting. Caution should be taken when prescribing multiple serotonin-altering medications, as serotonin syndrome is a potentially lethal side effect (see Serotonin Syndrome).3 Combining different medications or introducing new serotonin-altering medications to a dog’s treatment protocol can have deleterious effects; owners should be informed that, although uncommon, disinhibition of behavioral tendencies4 and/or development of aggression5 can occur at home. If adverse behavioral effects or signs of serotonin syndrome do not occur, the dose can be gradually increased over 1 to 2 days until the desired dose is reached or the desired effect is achieved.6 Alternatively, medications that do not alter serotonin levels (eg, α2 agonists, benzodiazepines, gabapentin) can be used.

Serotonin Syndrome

Serotonin syndrome, defined as a group of clinical signs associated with administration of serotonin-altering medications (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, antidepressants), although rare in veterinary medicine, can occur when multiple serotonin-altering medications are coadministered.18 Clinical signs of serotonin syndrome include altered mental status, agitation, nervousness, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, tremors, diarrhea, incoordination, increased heart rate and blood pressure, and hyperthermia.19 If a patient is already receiving medications for behavior alteration or other reasons, slow introduction of additional medications at lower doses is recommended. Any signs of agitation, restlessness, or myoclonus may suggest serotonin syndrome, and cessation of any additional serotonin-altering medications is recommended.

Common at-home administration protocols include administering oral trazodone, gabapentin, and alprazolam the day before the appointment and on the morning of the scheduled appointment or administering oral acepromazine, gabapentin, and alprazolam, potentially coadministered with maropitant (2 mg/kg PO q24h) to decrease the risk for vomiting after later administration of injectable sedatives (especially those that contain a pure μ opioid).7

Table 1: Perioperative Anxiolytic & Sedative Dosages in Dogs15-17

*Some dosages are anecdotal based on those used in the authors’ facility.

**Indicates commonly prescribed medications that, when combined with other serotonin-altering drugs, may place the patient at risk for serotonin syndrome. Careful and controlled introduction of medication combinations can help mitigate risks for serotonin syndrome development.

3. Sedation Administration

Many patients may become more stressed in the hospital waiting area, making it more difficult for sedative medications to reach full efficacy. The owner should be advised to place a muzzle and/or Elizabethan collar on the patient before or just after arrival, if possible. If available, other parts of the hospital (eg, parking lot, grassy relief area, barn) can be used as an environmental distraction for the patient during handling, waiting, and/or sedative administration.8 Because dogs use multiple cues (eg, visual, auditory, olfactory) to influence their behavior and/or reactions to their environment,9 soft and calm voices and limited personnel involvement are recommended. Pheromone sprays can help reduce anxiety but have not been shown to consistently reduce aggression in dogs.10

White coat syndrome (ie, the increase in a patient’s sympathetic response to stress due to the appearance of medical personnel in white coats or similar clothing) has been well documented in human medicine.11-13 To reduce the perceived threat of medical personnel, staff members who interact with the patient should avoid wearing white coats or similar hospital clothing while initially handling the patient (ie, from arrival to administration of injectable sedation). Typically, a coat or other outerwear is recommended to be worn over hospital clothing.11,12

Administering sedation via an intramuscular injection (Table 2) is preferable and can be done while the patient is walking on a leash, provided the person handling the patient and the person administering the drugs are both experienced enough for a rapid pelvic limb injection and subsequent patient reaction. These drugs are typically used in combination to provide deep sedation and/or general anesthesia. Combining different drug classes (Table 3) allows for a dose reduction in all agents, thereby potentially limiting negative adverse effects.

Table 2: Sedative Dosages in Dogs15-17

*Some dosages are anecdotal based on those used in the authors’ facility.

**Most drugs have a dose-dependent duration of effect (ie, higher doses usually prolong the effect); however, higher doses can also increase the frequency of adverse events.

Table 3: Sedative Combinations & Dosage Recommendations in Dogs15-17

*Opioids can be substituted within their drug class (eg, butorphanol substituted for hydromorphone) if goals for pain management require a different opioid.

**Doses can be adjusted based on recommended dosing ranges (Table 2). Some dosages are anecdotal based on those used in the authors’ facility.

†Any opioid can be substituted for hydromorphone based on availability.

Other handling techniques involve using a half-wall or chain link fence as a barrier between the patient and the injector/handler. An ideal sedative protocol, as recommended in human medicine, is rapid-acting with minimal side effects, although, without physical examination, adverse effects are difficult to predict in fractious patients.13 Of note, most anesthetic drugs are associated with some degree of risk14; this risk is increased in patients that are unable to be assessed for pre-existing comorbidities (eg, heart disease). Reversible drugs (eg, α2 agonists, opioids) are preferable, as their adverse effects can be mitigated with reversal agents if necessary.

Some patients may become sedate enough to lose airway protection. Supplies for intubation and appropriate ventilation should always be available for patients that show signs of requiring a protected airway or ventilatory support (eg, cyanosis, shallow breathing, regurgitation).

4. Patient Handling While Hospitalized

Fractious patients may require additional precautions for handling and drug administration while hospitalized. Standard monitoring procedures are recommended with the patient sedated or anesthetized. Hospitalization of fractious animals typically requires planning.

Placement of an IV catheter in a pelvic limb can be advantageous, as it provides more room between the patient’s head and the injection site. If pelvic limb catheter placement is not feasible, additional placement of long extension sets attached to the IV catheter (Figure 1) can facilitate semi-remote drug administration and provides an additional level of safety for the patient and staff.

FIGURE 1 A long extension set directly connected to the catheter, which is placed in the lateral saphenous vein. An injection port is accessible (out of frame).

An Elizabethan collar and/or basket muzzle can be used to provide additional safety for aggressive patients, and allowing patients to wear a harness with an attached leash while in a cage can be helpful when removing them from the confined space (Figure 2). Floor-level cages or runs are preferred, as they prevent the need for the handler to lift the patient out of the cage and onto the floor or into a carrier. Muzzles with connections suitable for oxygen delivery are also helpful for providing flow-by oxygen to aggressive patients.

To ensure patient and staff safety, an Elizabethan collar and a harness are used on the patient, with the leash attached to the harness and placed toward the cage door.

5. Recovery & Discharge

For outpatient procedures (eg, outpatient surgery, diagnostic procedures) requiring sedatives/anesthetic drugs, a basket muzzle can be modified so that the endotracheal tube can be removed through the muzzle, which allows the muzzle to be placed on the patient prior to extubation and be in place at the end of the procedure (Figure 3). This facilitates safety in the recovery period while still allowing the patient to be closely monitored.

Basket muzzle modified to facilitate extubation (A). Placement of the pilot balloon and endotracheal tube ties through the end of the muzzle is necessary to avoid difficulty extubating the patient (B).

Intravenous catheters can be removed just before discharge. With all tape removed and a bandage left over the catheter, the extension line, which is attached to the catheter hub, can be pulled, thus removing the catheter while keeping the bandage in place for hemostasis (see Step-by-Step Catheter Removal Video). Sedatives can be administered intravenously just before catheter removal at the time of discharge and can facilitate a smooth transition from the hospital to the transportation vehicle. The owner should be made aware of the expected nature and duration of the sedation protocol.

Conclusion

Careful planning, communication, and preparation can facilitate a safe and productive appointment for fractious patients that need to be sedated or anesthetized. Multimodal pharmacologic restraint, along with modified approaches to drug administration and patient handling, can mitigate most of the issues encountered with aggressive patients in the hospital setting.