Conjunctivitis is a common ocular disorder that affects both cats and dogs. Many clinical aspects of conjunctivitis—including clinical manifestations and basic clinical evaluation—are similar between species. Both feline and canine conjunctivitis are also associated with numerous and diverse potential etiologies, many of which are shared between cats and dogs.

There are, however, several critical differences between dogs and cats with conjunctivitis that should be considered when managing cases; following are the author’s top 5.

1. Clinical Frequency of Herpetic Conjunctivitis

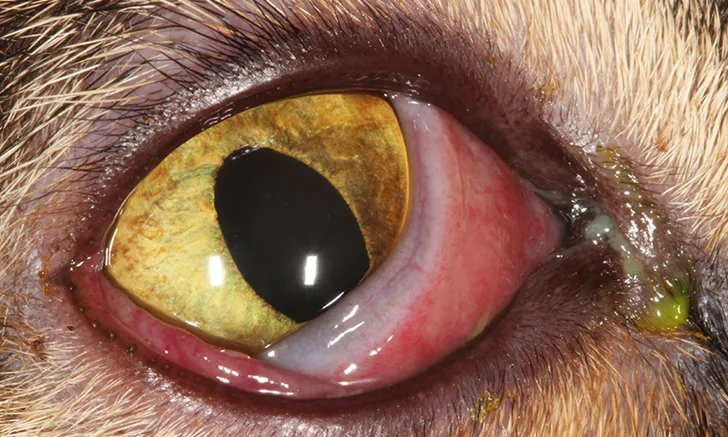

Herpesvirus infection is a cause of infectious conjunctivitis in both cats and dogs. Clinically, both feline herpesvirus-1 and canine herpesvirus-1 produce similar ocular lesions; however, the frequency of herpetic conjunctivitis in cats is much higher than what is observed in dogs.1,2 The pathophysiologic basis for this discrepancy is not currently known, but it may be associated with the relative ability of the host immune system to prevent viral reactivation from latency.3 Feline herpesvirus-1 is among the most common, if not the most common, etiologies of conjunctivitis in cats and should be considered in any cat that has conjunctivitis (Figure 1).

Feline herpesvirus-1 conjunctivitis. Conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, mucopurulent ocular discharge, and nictitating membrane elevation are present.

Clinically, conjunctivitis associated with canine herpesvirus-1 infection is much less common and is often observed in specific clinical scenarios (eg, young dogs, dogs with immunomodulating systemic conditions, dogs receiving immunosuppressive therapeutics).4

2. Etiologic Significance of Bacteria

Bacterial infection is not a recognized etiology of primary conjunctivitis in dogs. However, secondary bacterial conjunctivitis occurs commonly in dogs, exacerbates clinical lesions, and complicates the management of conjunctivitis associated with other primary causes.5 Development of bacterial conjunctivitis in dogs requires anatomic, physiologic, or immunologic compromise of the canine conjunctival surface. Underlying conditions that predispose dogs to secondary bacterial conjunctivitis include keratoconjunctivitis sicca, entropion, and conjunctival foreign bodies (Figure 2).6 Resolution of bacterial conjunctivitis in dogs requires identification and correction of the underlying cause.

Secondary bacterial conjunctivitis in a dog with uncontrolled keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Copious and malodorous mucopurulent ocular discharge is present with conjunctival hyperemia and keratitis. Clinical findings included corneal vascularization, pigmentation, and fibrosis.

Distinct from canine conjunctivitis, both Chlamydia felis and Mycoplasma spp infections are common primary causes of feline conjunctivitis.7,8 Infection with these microorganisms does not require pre-existing ocular disease to produce conjunctivitis. Chlamydia spp and Mycoplasma spp infections produce a similar clinical appearance and are often associated with chronic, severe conjunctivitis. Treatment should include appropriate antimicrobial therapy (eg, topical oxytetracycline or erythromycin, systemic doxycycline or azithromycin). Doxycycline (5-10 mg/kg PO every 12-24 hours for 3-4 weeks) is generally regarded as the treatment of choice for cats with C felis conjunctivitis. Doxycycline (5-10 mg/kg PO every 12-24 hours for 2 weeks) or azithromycin (5-10 mg/kg once daily for 5 days) can be used as an alternative to topical treatment for mycoplasmal conjunctivitis. Doxycyline should not be administered to cats via dry pilling.

3. Types of Allergic Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis can be associated with a variety of allergic conditions. Two of the most common types of allergic conjunctivitis are atopic conjunctivitis and drug reaction conjunctivitis. Atopic conjunctivitis is very common in dogs and is typically accompanied by atopic dermatitis.9 Dogs frequently display mild and seasonal conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, ocular pruritus, and development of conjunctival follicle formation with chronicity (Figure 3). Although this form of conjunctivitis also occurs in cats, it is observed much less frequently in this species.

Atopic conjunctivitis in a young dog. Epiphora, mild conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, and numerous conjunctival follicles are present in the inferior conjunctival fornix.

Drug reaction conjunctivitis is a hypersensitivity reaction that can result in severe clinical lesions and occurs in dogs and cats with similar frequency. Blepharitis, often with dermal ulceration, and keratitis are frequently present concurrently.10 Ophthalmic medications containing neomycin, carbonic-anhydrase inhibitors, and antivirals (eg, cidofovir) are among the most common medications associated with drug reaction allergic conjunctivitis in dogs and cats.11

4. Specific Types of Immune-Mediated Conjunctivitis

Immune-mediated causes of conjunctivitis are specific idiopathic ocular conditions for which no underlying cause has been identified and that have a presumed autoimmune pathophysiology. These conditions are species-specific and vary greatly between dogs and cats.

In dogs, these conditions include diffuse episcleritis, nodular granulomatous episcleritis, and atypical pannus. The conjunctiva is the primary focus of clinically recognizable inflammation with diffuse episcleritis and nodular granulomatous episcleritis. Both conditions clinically appear as conjunctival hyperemia and thickening that is often accompanied by peripheral keratitis adjacent to the conjunctival lesions (Figure 4).12 Nodular granulomatous episcleritis is additionally associated with formation of one or more distinct, proliferative, firm, smooth-surfaced, subconjunctival masses.

Nodular granulomatous episcleritis in a dog. Conjunctival hyperemia and thickening associated with a distinct, elevated, smooth-surfaced subconjunctival mass in the temporal bulbar conjunctiva are present. In addition, peripheral keratitis has developed adjacent to the conjunctival lesions.

Atypical pannus, or plasmoma, is an alternative presentation of pannus (ie, canine chronic superficial keratitis) in which the primary clinical focus of lesions is the conjunctiva, as opposed to the cornea. Atypical pannus presents clinically as a bilateral hyperemic thickening of the nictitating membrane conjunctiva associated with multifocal follicle formation and varying degrees of conjunctival depigmentation and pigmentation.13

In cats, immune-mediated causes of conjunctivitis include eosinophilic conjunctivitis, lipogranulomatous conjunctivitis, and epitheliotropic mastocytic conjunctivitis. Clinically, eosinophilic conjunctivitis appears as unilateral or bilateral conjunctivitis, often with concurrent keratitis, and is frequently associated with the formation of superficial white nodules or plaques on the epithelium.14 Some cats also have concurrent eyelid margin depigmentation, thickening, or ulceration (Figure 5). Although most cats with eosinophilic conjunctivitis have concurrent keratitis (more correctly referred to as eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis), some cases occur in the absence of clinical corneal disease. Diagnosis is achieved through detection of eosinophils on conjunctival cytology.

Eosinophilic conjunctivitis in a cat. Conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, mucoid discharge, and concurrent eyelid margin depigmentation are present.

Lipogranulomatous conjunctivitis is characterized by the formation of nonulcerative white nodules in the palpebral conjunctiva adjacent to the eyelid margin. The nodules are composed of macrophages and lipids.15

Feline epitheliotropic mastocytic conjunctivitis is a condition associated with proliferative or nodular conjunctival lesions.16 Papillary epithelial hyperplasia and an idiopathic mixed inflammatory infiltrate of the conjunctiva (eg, numerous intraepithelial and subepithelial mast cells) are present histologically.

5. Empiric Use of Topical Corticosteroids

Conjunctivitis is a relatively nonspecific ocular condition that is associated with a variety of different potential etiologies. A thorough history should be obtained and physical and ocular examination and appropriate diagnostic tests performed to identify the specific etiology of the conjunctivitis whenever possible. If no contraindications are found during initial examination, use of empiric topical corticosteroid therapy can be cautiously considered in dogs while awaiting diagnostic test results or in cases in which no underlying etiology is identified. In cats, use of empiric topical corticosteroids is strongly discouraged, as many of the common etiologies of feline conjunctivitis (eg, feline herpesvirus-1, C felis infection) are worsened by this therapy, and it can result in severe ocular sequelae.17 Topical corticosteroids should be reserved for cases of feline conjunctivitis in which a definitive and appropriate diagnosis is identified.

Conclusion

Although many similarities exist between dogs and cats with conjunctivitis, the discussed clinical differences between these species should always be considered when managing cases. Recognition of these differences can contribute to improved and optimal outcomes.