Collection of accurate diagnostic data should include blood film examination and automated hematology system results. Automated hematology analyzers are excellent tools for in-clinic laboratories, but they do not replace blood film examination.1 Thus, microscopic examination of a blood film is necessary with every CBC for accurate and precise diagnostic interpretation.2

Following are the top 5 clinically significant abnormalities that may be missed when a blood film is not examined in conjunction with a CBC, according to the author.

1. Left Shift

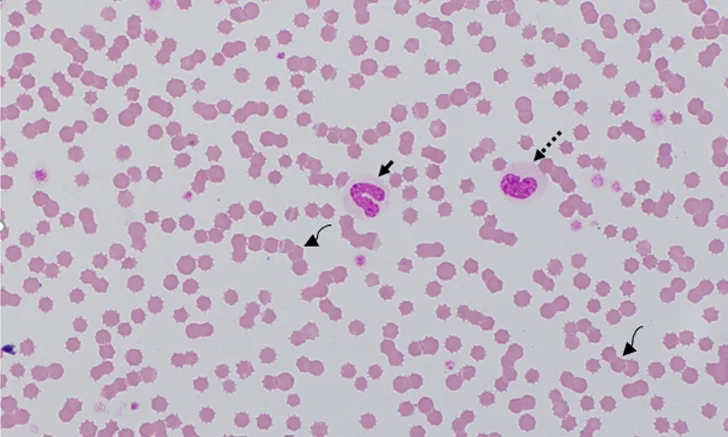

A left shift is an increased concentration of nonsegmented (ie, immature) neutrophils in blood. These immature cells are usually band neutrophils (Figure 1) but may also include younger neutrophils (eg, metamyelocytes, myelocytes) in cases of severe inflammation. Inflammation and increased tissue demand for neutrophils cause cytokine-mediated release of neutrophils from the bone marrow, resulting in exhaustion of the neutrophil storage pool and neutrophil release from the maturation pool.2

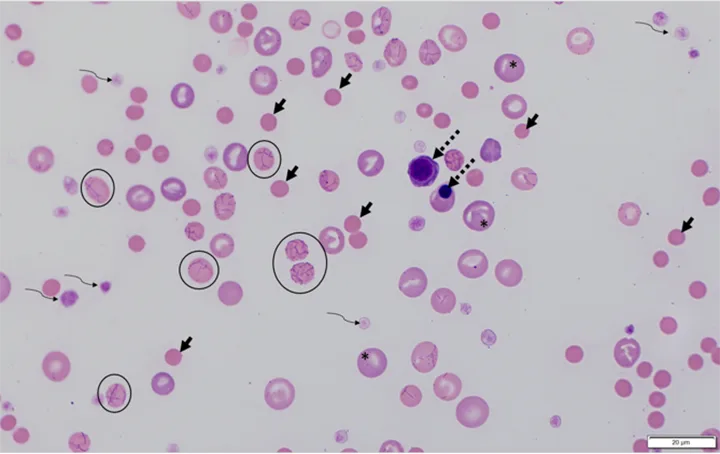

Blood film from a 7-month-old cat recovering from panleukopenia. Concurrent CBC data indicated that total WBC and neutrophil concentrations were within the reference interval. The cat had neutropenia 5 days prior. Bone marrow recovery resulted in the release of immature toxic neutrophils, including bands (solid arrow), metamyelocytes (dashed arrow), and myelocytes (not shown). The rouleaux (curved arrows), characterized by linear aggregates of RBCs, resemble a stack of coins. In dogs and cats, rouleaux tends to occur with hyperglobulinemia and/or hyperfibrinogenemia.7 Modified Wright’s stain, 1000× magnification

Identification of a left shift helps differentiate neutrophilic leukogram patterns.2 The most common leukogram pattern confusion is differentiation between an acute inflammatory leukogram (increased number of bands ± other immature neutrophils) and a stress/corticosteroid-mediated leukogram (increased number of segmented neutrophils and rare to no bands), as both patterns may demonstrate neutrophilia and lymphopenia.2

An inflammatory leukogram cannot be ruled out simply because the WBC or neutrophil concentration is within the reference interval, especially in clinically ill patients. Some, or even most, of those neutrophils might be immature.3

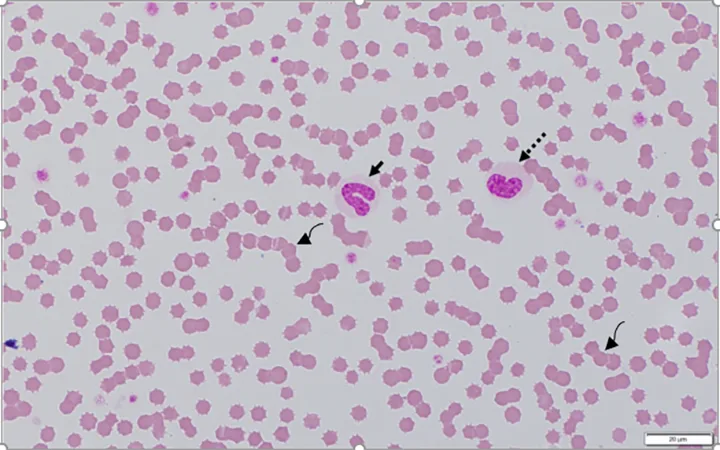

2. Platelet Clumps

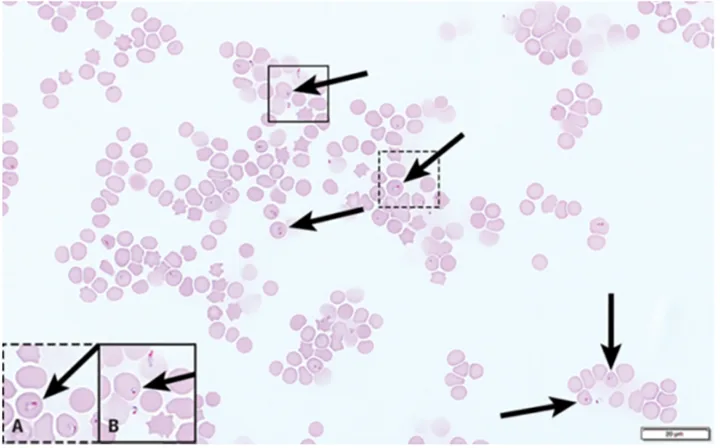

Identifying platelet clumps (Figure 2) on a blood film can have several implications, with the most important being a false decrease in platelet concentration reported by the hematology analyzer. This may lead to a false diagnosis of thrombocytopenia in a patient with platelet concentration in the reference interval. Therefore, confirmation of analyzer-reported thrombocytopenia via blood film examination is essential.<sup4 sup>

Platelet clumps (A; circled) identified at the feathered edge on a blood film from a dog (200× magnification). Higher magnification (B; 600×) of the large platelet clump shown in A. Modified Wright’s stain

Platelet clumps usually indicate the platelets were activated during collection; this is a common finding in all species, especially cats.4,5 However, slow phlebotomy or inappropriate mixing of the EDTA tube can also result in platelet clumps.

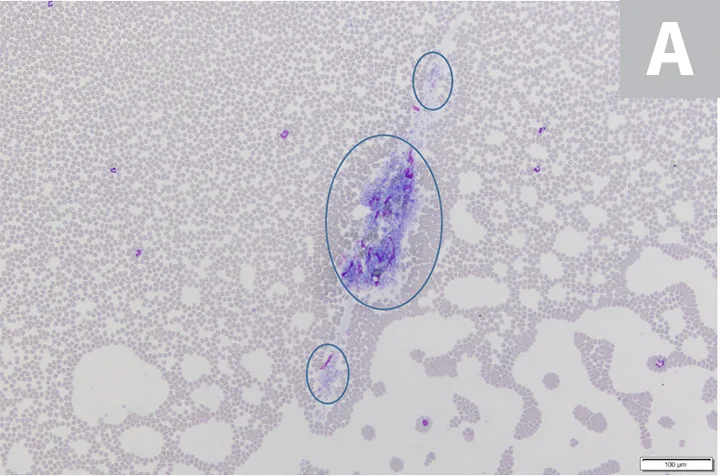

3. Morphologic Changes in Erythrocytes

Changes in erythrocyte color, shape, and size are often helpful indicators of disease processes (most commonly, the cause of anemia).6 Listing and explaining the various morphologic changes that occur in erythrocytes are beyond the scope of this article, but a few examples are provided.

Polychromatophils (Figure 3) are immature anucleate erythrocytes released early from bone marrow on increased erythrocyte demand. They appear blue to purple when stained with a routine Romanowsky-type stain (eg, Wright’s, modified Wright’s, Quick), and are usually larger than mature erythrocytes. Polychromatophils are identified as reticulocytes when stained with new methylene blue.1 Observing these cells in the blood film is important because they indicate accelerated erythropoiesis when present in a sufficiently increased concentration. When the concentration increases due to anemia, these cells represent accelerated erythropoiesis, bone marrow regeneration, and an etiology of either blood loss or hemolysis.6,7

Blood film from a dog with IMHA caused by Mycoplasma hemocanis (RBCs with organisms attached; circles) and characteristic of regenerative anemia. Spherocytes (solid arrows; not all spherocytes are indicated) are identified by their darker pink staining, smaller diameter, and lack of central pallor. Polychromatophils (asterisks; not all indicated) and nucleated RBCs (dashed arrows), which are identified by most hematology analyzers as WBCs, can be seen. Platelets (curved arrows) are also present. Modified Wright's stain, 1000× magnification

Schistocytes are fragmented erythrocytes that result from erythrocyte trauma (most commonly due to fibrin strands in the vasculature), increased turbulence, or excessively fragile RBCs. Pathologic conditions that often result in schistocytosis may include disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemangiosarcoma, heartworm disease, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, myelofibrosis, endocarditis, and iron deficiency.7

Spherocytes (Figure 3) are most easily recognized in dogs and appear round with a smaller diameter than normal RBCs and lack central pallor. They also stain darker pink or red as compared with typical erythrocytes because the hemoglobin is concentrated into a smaller space due to loss of membrane.

Spherocytes most commonly aid in the diagnosis of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA) and can be difficult to discern in noncanine species because the normal healthy erythrocytes of other domestic species are smaller and often lack central pallor in health.7 Other concurrent findings that support a diagnosis of IMHA may include RBC agglutination and ghost cells.

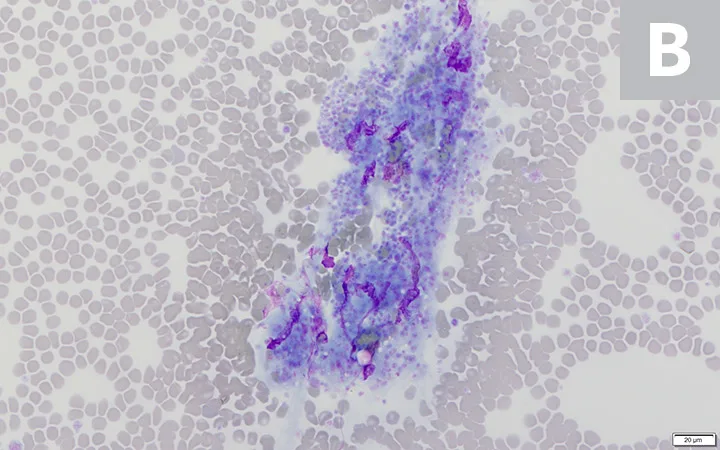

4. Infectious Agents

Although development of PCR assays allows accurate identification of many hemoparasites and other infectious agents, examination of a blood film is a valuable first-line tool that can narrow the need for PCR and other costly or potentially invasive diagnostic tests. Several infectious agents can be seen on blood film examination, including but not limited to intracellular protozoal parasites (eg, Babesia spp, Hepatozoon spp, Cytauxzoon spp; Figure 4), rickettsial organisms (eg, Anaplasma spp, Ehrlichia spp), epicellular bacteria (eg, Mycoplasma spp; Figure 3), fungal structures (eg, Histoplasma spp), and viral inclusions from distemper.3,8 Presumption of a potential diagnosis based on the blood film can allow more time and funds for treatment, as these patients are often presented in a critical state.

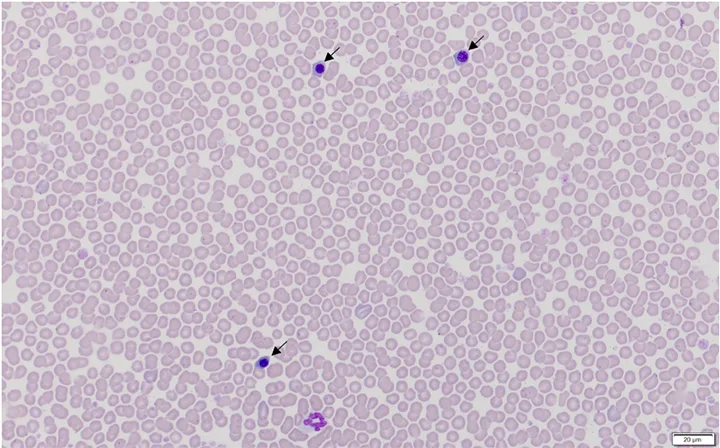

Peripheral blood smear (feathered edge) from a cat with Cytauxzoon felis; characteristic signet-ring–shaped piroplasms (arrows) can be seen in the RBCs. Not all organisms are indicated. Polychromasia, platelets, and WBCs are absent. This is consistent with nonregenerative anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia.10 Modified Wright’s stain, 1000× magnification

5. Misclassified or Atypical Cells

Nucleated RBCs (nRBCs) are misclassified as WBCs by most hematology analyzers.2 As a result, increased circulating nRBCs (rubricytosis) can falsely increase the reported WBC concentration. Correction of the WBC concentration should be performed if there are >10 nRBCs/100 WBCs as determined via manual differential when viewing the blood film.2 Correcting the WBC concentration for rubricytosis can be calculated as [corrected WBC] = [measured WBC] × (100/[100 + nRBC]).2 The measured concentration is the value determined by the analyzer.2

It is also important to identify increased nRBCs for diagnostics. Increased circulating nRBCs can be appropriate (ie, part of the response to regenerative anemia subsequent to blood loss or hemolysis) or inappropriate (ie, concurrent with nonregenerative anemia or absence of anemia). If the patient is anemic and polychromasia and reticulocytosis are present, rubricytosis is considered appropriate (Figure 3) because it is most likely part of the regenerative response.

Rubricytosis is inappropriate if the patient has increased nRBCs and is either not anemic or anemic without reticulocytosis (ie, patient has nonregenerative anemia). Bone marrow injury (eg, thermal injury/heatstroke [Figure 5], hypoxia, endotoxemia, lead toxicosis) is a common cause of inappropriate rubricytosis.7

Blood film from a dog with heatstroke and associated inappropriate rubricytosis (nRBCs/metarubricytes [arrows]) caused by thermal injury to bone marrow. Hematocrit was 53%. Modified Wright’s stain, 600× magnification

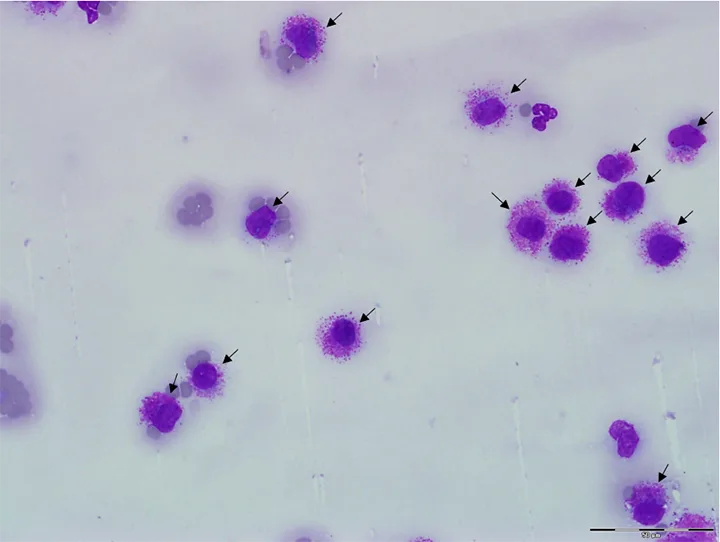

Neoplastic cells (Figure 6) can also be identified on a blood film but are not correctly identified as such by a hematology analyzer. Diagnosing a specific type of neoplasia (eg, mast cell neoplasia, lymphoid or myeloid leukemia) may or may not be possible using a blood film alone, but finding atypical cells can guide a potential diagnosis not previously considered.2,9

Blood film from a cat with disseminated mast cell neoplasia. Many mast cells are seen at the feathered edge (arrows) and throughout the entire smear (not shown). Modified Wright’s stain, 1000× magnification

Conclusion

Microscopic examination of a blood film should be a part of every CBC evaluation to ensure important patient information is not missed.7 Although most analyzers provide a 5-part WBC differential, this feature does not replace microscopic assessment for confirmation of cell identification or presence of a left shift, platelet clumps, infectious agents, or abnormal cells that may be misclassified. Blood films should be prepared immediately after blood collection for best results and to avoid changes that may occur with sample aging (eg, cell swelling, detachment of hemotropic mycoplasma organisms).