Tooth Resorption

Brook A. Niemiec, DVM, DAVDC, DEVDC, FAVD, Veterinary Dental Specialties & Oral Surgery, San Diego, California

Gottfried Morgenegg, DVM, Tierzahnarzt, Obfelden, Switzerland

Cedric Tutt, BVSc(Hons), MMedVet(Med), DEVDC, MRCVS, Cape Animal Dentistry Service, Cape Town, South Africa

The WSAVA Dentistry Series is developed by Dr. Brook Niemiec in association with the World Small Animal Veterinary Association and Clinician’s Brief.

THE CASE

A 7-year-old spayed domestic shorthair cat was presented for oral pain and inappetence following a professional dental cleaning performed at her regular clinic. Several teeth were extracted at that time due to tooth resorption (TR). No dental radiographs were taken. The patient was initially referred to an internal medicine specialist, who performed a thorough diagnostic investigation for systemic conditions, which included abdominal ultrasonography and CBC, serum chemistry profile, urinalysis, and total thyroxine levels; no significant abnormalities were identified.

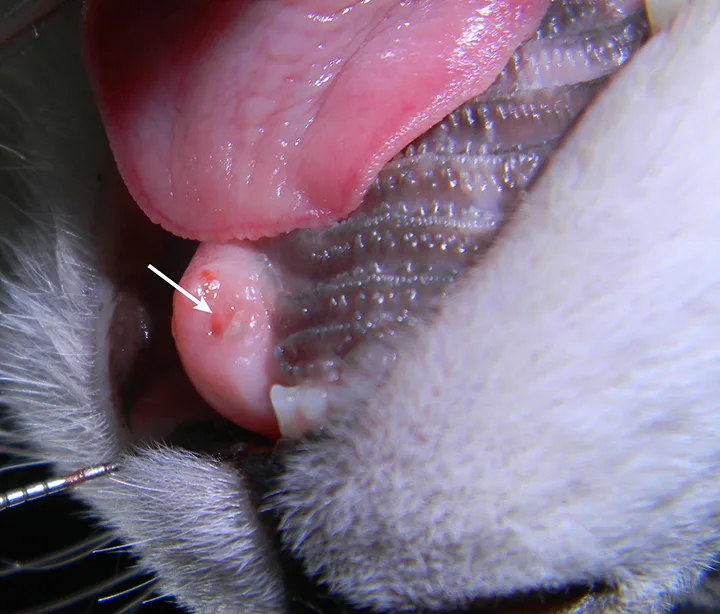

The patient periodically pawed at her face and shook her head. Oral examination revealed unhealed extraction sites with visible protrusion of tooth fragments through the gingiva (Figure 1). The areas were inflamed, and purulent exudate was present in the open alveolus of the right mandibular canine tooth (Figure 2; see Tooth Numbering).

FIGURE 1

Intraoral image of the left maxillary canine revealing inflammation and a tooth fragment (arrow) extending into the oral cavity

TOOTH NUMBERING

Find information on identifying corresponding tooth numbers at avdc.org/Triadan_Tooth_Numbering_System.pdf

Diagnostics

A complete oral examination and full-mouth dental radiographs were performed with the patient anesthetized. The detailed oral examination confirmed unhealed extraction sites with sharp crown fragments protruding from the alveoli into the oral cavity. In addition, an advanced TR lesion was noted affecting the left maxillary third premolar tooth (Figure 3). Dental radiographs confirmed advanced type 2 resorption affecting all involved teeth, as well as oral extension of the remaining tooth structure (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3

Intraoral radiograph of the left maxilla revealing type 2 tooth resorption on the third premolar (arrow). Extraction is indicated.

Treatment & Follow-Up

After cleaning of the remaining teeth, regional nerve blocks were performed (bupivacaine 0.5% [0.2 cc at each site]), and buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg sublingual) was administered as part of a multimodal analgesia approach. The patient was premedicated with midazolam (0.2 mg/kg IV), and anesthesia was induced with propofol (to effect) and maintained with isoflurane. Extractions and crown amputations (where indicated), alveoloplasty, and closure of the surgical sites via buccal mucosal flaps were also performed. The patient was discharged the same evening with appropriate pain management, which included sublingual buprenorphine and oral robenacoxib.

The procedures removed the source of oral pain and allowed the patient to return to normal eating the night of surgery. Comfort was provided via perioperative analgesics and local/regional blocks. Recheck examination 2 weeks later revealed healed surgery sites, and the owner reported the cat to be more active and interactive than before surgery.

Discussion

TR is common in cats, occurring in 30% to 60% of all feline patients, and affected cats typically have more than one tooth involved.1-4 In addition, incidence increases with age.1,2,4-6 The mandibular third premolars are the most commonly affected teeth, followed by molars and canines.5,6 TR is progressive, with no known treatment or prevention. Lesions are typically painful, but patients rarely demonstrate outward clinical signs of oral pain.3,7,8

Types of Tooth Resorption3,8-10

There are 2 main types of TR: type 1 and type 2. Type 1 lesions present with advanced tooth/root resorption but without replacement by bone, whereas type 2 lesions typically present with the lost areas of tooth replaced by bone (ie, replacement resorption). Type 3 TR describes a tooth that has properties of type 1 TR on one root (or area) and type 2 on another.

Stages of Tooth Resorption

TR can be further categorized by the location and degree of resorption. Regardless of the type of resorption (replacement or not), staging can be performed (see Stages of Tooth Resorption). Although this is largely an academic exercise, staging can be helpful in determining appropriate care in some cases.

STAGES OF TOOTH RESORPTION

Find a detailed description of the stages of tooth resorption, along with images, from the American Veterinary Dental College at avdc.org/Nomenclature/Nomen-Teeth.html#resorption

Etiology

Although numerous theories regarding TR etiology exist, none have been confirmed. TR is known to be caused by odontoclasts (ie, normal cells responsible for remodeling tooth structure). In the normal physiologic process, the resorbed tooth structure is replaced by odontoblasts; however, in TR, these cells are activated and do not downregulate. This, in combination with lack of normal repair, results in tooth destruction.11 Type 1 TR is typically associated with inflammation (eg, caudal stomatitis, periodontal disease).12 In these cases, it is thought that odontoclasts are activated by soft tissue inflammation. Type 2 lesions, in contrast, are generally seen in otherwise healthy mouths; however, the lesions often create local gingivitis. Type 2 TR is a noninflammatory replacement resorption that typically results in ankylosis. The etiology of type 2 TR remains unproven. Lesions start on the root and thus may be seen on dental radiographs prior to oral evidence.

Diagnosis & Treatment13-17

Dental radiographs are crucial in establishing proper diagnosis and treatment. Teeth with type 1 TR have normal root density in some areas, as well as a well-defined periodontal space. There is generally a clearly defined root canal in the intact part of the tooth. This type may involve significant resorption of the tooth and/or root(s) that is not replaced by bone. These teeth must be completely extracted.

Teeth with type 2 TR have undergone significant replacement resorption. In these cases, the lost root structure is replaced by bone. Therefore, teeth with type 2 TR have a different radiographic density as compared with normal teeth. Radiographic findings typically include areas with no discernible periodontal ligament space (ie, dentoalveolar ankylosis) or root canal. In advanced lesions, there is little to no discernible root structure (ie, ghost roots).

Crown amputation is an accepted therapy only in appropriately selected cases in which dental radiographs confirm the following:

Advanced type 2 resorption

No periodontal ligament

No endodontic system

No evidence of periodontal disease

No evidence of endodontic pathology

Crown amputation requires creation of a gingival or mucoperiosteal flap and removal of the tooth structure to approximately 1 mm below the alveolar margin using a carbide bur on a high-speed, water-cooled handpiece. Alveoloplasty is performed to remove any shards of bone prior to closure of the surgical flap. Crown amputation is not recommended in cases of caudal stomatitis.

Improper treatment that leaves patients in pain, as well as with untreated inflammation and infection, is a significant animal welfare concern. In this patient, the open extraction sites and rough tooth surface allowed for continued discomfort as well as inflammation and infection, causing patient distress manifested by anorexia, pawing at the mouth, and head shaking. Practitioners are urged to further their skills in treating this condition by engaging in hands-on training in dental radiography and extraction techniques.