Tooth Fracture

Gottfried Morgenegg, DVM, Tierzahnarzt, Obfelden, Switzerland

Brook A. Niemiec, DVM, DAVDC, DEVDC, FAVD, Veterinary Dental Specialties & Oral Surgery, San Diego, California

David Clarke, BVSc, DAVDC, FAVD, MANZCVS, Dental Care for Pets, Victoria, Australia

Rod Jouppi, DVM, Laurentian University, Ontario, Canada

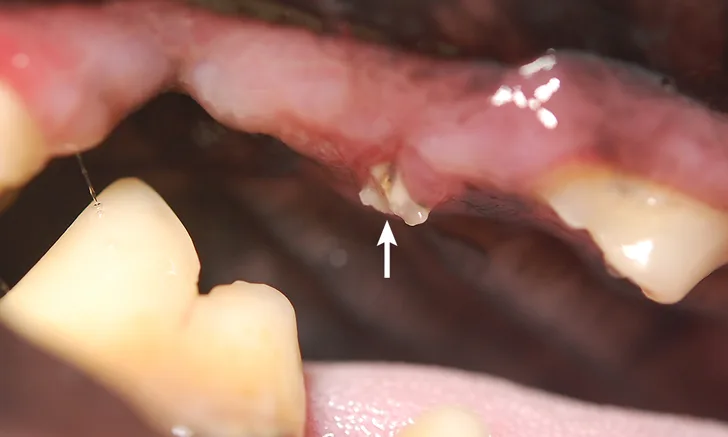

Intraoral image of the right maxillary fourth premolar showing inflammation and a root fragment extending into the oral cavity (arrow)

THE CASE

Sam, a 12-year-old retriever, was presented for owner-observed signs of pain while eating (ie, moving food in his mouth to chew, occasional vocalization). His owners reported that he also exhibited other signs, including aggressively chewing on multiple objects.

On physical examination, recent, unilateral, mild hemorrhage of the lip commissure was identified. An uncomplicated crown fracture of the right maxillary fourth premolar (with the fragment extending into the gum) was presumptively diagnosed. The tooth fragment was removed with the patient under general anesthesia. Because the pulp was apparently not directly exposed, no further treatment was performed. Dental radiography was not performed.

Sam was presented again a few months later for swelling below his right eye. An abscess from the right maxillary fourth premolar was presumptively diagnosed, and the tooth was sectioned and removed with a closed extraction technique. Dental radiography, again, was not performed.

After several months, the oral wound had not healed appropriately, and the patient demonstrated apparent continued discomfort, especially while eating. He was referred to a specialist for further treatment. Oral examination on referral revealed that the extraction site of the right maxillary fourth premolar was unhealed, with a root fragment extending from the inflamed gingiva (Figure 1).

Diagnostics

A full physical examination with preoperative testing (ie, CBC, serum chemistry profile, urinalysis) revealed no significant abnormalities. A complete oral examination and full-mouth radiography were performed with the patient under general anesthesia.

Oral examination confirmed an unhealed extraction site of the right maxillary fourth premolar with a root fragment protruding into the oral cavity. Periodontal disease of the left maxillary fourth premolar (Figure 2) and a complicated crown fracture of the right maxillary canine (Figure 3) were also identified.

Dental radiographs confirmed the root fragment of the right maxillary fourth premolar had been retained (Figure 4). Periapical rarefaction (ie, periapical lucency) and periodontal disease of the right maxillary canine were also confirmed on radiographs; comparison with the contralateral left maxillary canine revealed that the canine tooth had been nonvital for several months, as the pulp cavity of the right maxillary canine had failed to narrow (Figures 5 and 6).1 Dental radiographs of the left maxillary fourth premolar revealed fractures of the mesiobuccal and mesiopalatinal roots in addition to advanced periodontal disease of the distal root (Figure 7).

FIGURE 2A

Intraoral image (A) and close-up view (B) of the left maxillary fourth premolar showing signs of advanced periodontal disease. Gingivitis, gingival recession, furcation involvement of the left maxillary fourth premolar, and gingivitis of the third and fourth mandibular premolars and the first mandibular molar can be seen.

Treatment & Follow-Up

After the remaining teeth were cleaned, maxillary nerve blocks were performed and IV analgesia administered as part of a multimodal analgesia approach. Surgical extractions—which included removal of the mucogingival flaps and buccal bones and closure of the surgical sites—of the maxillary fourth premolars and the right maxillary canine were performed.2

Sam was discharged the same day on an oral NSAID to be administered daily for the next 4 days. His recovery was uneventful, and he started eating soft food the day after surgery.

Discussion

Tooth fractures are common in dogs and cats and are typically incidental findings. In a study, fractured teeth were diagnosed in ≈50% of companion animals.3

Classification of Tooth Fractures

Tooth fractures can be classified based on the amount of tooth structure (ie, enamel, dentin, cementum) exposed and whether the dental pulp tissue is directly exposed. An injury that does not expose the pulp is considered uncomplicated; direct pulp exposure is considered complicated.4

All vital teeth with direct pulp exposure are painful.5 The exposed pulp may become infected by oral bacteria, which can lead to pulpitis and pulp necrosis.

Uncomplicated Tooth Fractures

Special attention should be paid to uncomplicated crown fractures, as progressive clinical implications are typically underestimated. Dentinal tubules are exposed in almost all cases of uncomplicated crown fractures and can have several consequences:

Pain can be felt due to dentinal sensitivity.6

Bacteria can penetrate the tubules and infect the pulp without direct exposure of the pulp, resulting in pulpitis and pulp necrosis.7 Infection can extend through the apical delta and affect the periapical bone (ie, periapical rarefaction; Figure 8), which has been reported to occur in 24.3% of uncomplicated fractures of maxillary fourth premolars.8 If not recognized, the disease may end in abscessation with typical swelling (Figure 9) or in a fistula.

The rough surface of a fractured tooth enables faster plaque and calculus accumulation, which can hasten the onset of periodontal disease.

FIGURE 8A

Intraoral image of a right maxillary fourth premolar with an uncomplicated crown fracture (A) and the correlating intraoral radiograph showing advanced periapical rarefaction (B; arrows)

Diagnosis & Treatment

Because the appearance of the crown does not always correlate with what is happening below the gumline, dental exploration and radiography are necessary for thorough examination of a fractured tooth. Uncomplicated crown fractures that appear harmless can have severe endodontic consequences seen on dental radiographs (Figure 8).9 Treatment options are directly related to the type and degree of damage, as well as the presence or absence of endodontic disease.10 Any complicated fracture (ie, involving direct pulp exposure) should be treated via extraction or root canal therapy. If a therapeutic delay is necessary, pain management should be provided until surgery can be performed; antibiotics are typically not indicated in these cases.11

Treatment for dentin exposure (ie, uncomplicated fracture) is recommended to reduce sensitivity, block the pathway for infection, and smooth out the tooth, which should decrease periodontal disease.12

Dental radiography should be performed prior to treatment to ensure there is no existing endodontic disease. If evidence of endodontic inflammation and/or infection is noted on dental radiographs, root canal therapy or extraction is typically required.

Animal Welfare Relevance

Animals rarely show signs of oral pain, despite their nociceptive pathways functioning similarly to those of humans.13 Clinicians are responsible for recognizing when an animal is in pain and reacting accordingly. The intense pain from pulp exposure and the long duration required for an infection to develop outward clinical signs are of great animal welfare relevance. Animal welfare is gaining in importance, and neglecting guidelines may lead to future consequences.

Conclusion

Sam’s case demonstrates the importance of quickly performing a full dental examination, including dental radiography, with the patient under general anesthesia. Clinicians should have the minimum equipment and expertise needed if dental procedures are expected to be performed. Referral should be considered if the clinician is not properly equipped to handle these dental conditions.