Carly, a 2-year-old spayed domestic shorthair cat, was referred to an after-hours emergency service after severe anemia (packed cell volume, 16%) and a heart murmur were diagnosed by the referring clinician. According to the pet owner, Carly had a history of progressive lethargy; she had stopped eating 3 days prior to presentation and had a 1-month history of inconsistent appetite. Prior to adoption (≈3 to 4 months before presentation), she was an outdoor cat.

Physical Examination

On physical examination, Carly was quiet, alert, and responsive with pale and tacky mucous membranes. Capillary refill time was within reference range. Other abnormalities included pyrexia (104.1°F [40.1°C]), tachycardia (220 bpm), and tachypnea (40 breaths per minute). FeLV/FIV results were negative.

Diagnosis

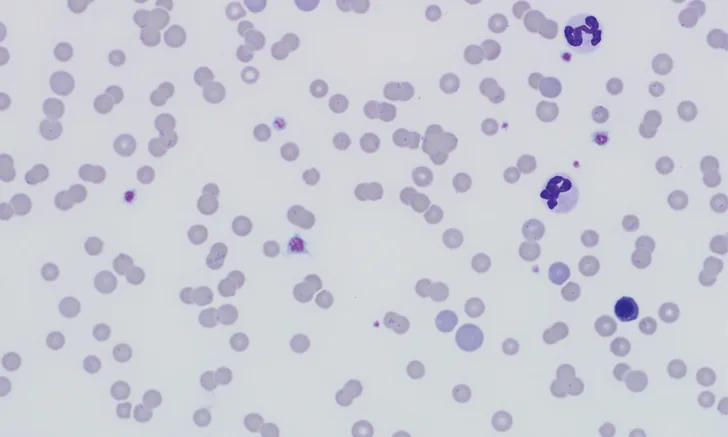

CBC revealed macrocytic (mean corpuscular volume, 51.3 fL; reference interval, 41-51 fL), hypochromic (mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, 31.6 g/dL; reference interval, 32-35 g/dL), and regenerative (reticulocyte count, 0.1 x106/µL; reference interval, 0.01-0.06 x106/µL) anemia (packed cell volume, 15%; reference interval, 35%-50%). Leukogram was unremarkable. Many small cocci and ring-shaped structures (Figures 1-3) adhered to the RBC surface were observed on blood smear. Structures were distributed individually, in clusters, and occasionally in chains.

Serum chemistry profile indicated mild hyperbilirubinemia (0.3 mg/dL; reference interval, 0-0.2 mg/dL), which was likely prehepatic secondary to hemolysis, and mild hypoalbuminemia (2.9 g/dL; reference interval, 3.2-4.5 mg/dL) likely due to inflammation, as albumin is a negative acute-phase protein. Bilirubinuria was also observed.

FIGURE 1

Blood smear showing numerous erythrocytic bacteria typical of Mycoplasma haemofelis (solid black arrows), polychromatophilic cells (solid white arrows), agglutination (dotted white arrow), and nucleated RBC (dotted black arrow). Modified Wright’s stain, 1000× magnification. Inset is a magnified image of the central boxed region.

DIAGNOSIS: MARKED REGENERATIVE ANEMIA DUE TO ERYTHROPARASITE MYCOPLASMA HAEMOFELIS

Treatment

Carly received pradofloxacin oral solution (7.5 mg/kg PO) once daily for 2 weeks. Because of the organism’s classic appearance and rapid response to therapy during the weekend of presentation, no molecular testing was performed. After 2 weeks, Carly’s anemia had greatly improved (packed cell volume, 32%), the heart murmur had resolved, and no organisms were observed on blood smear. Pradofloxacin was continued for an additional 2 weeks at the same dosage, after which the anemia had completely resolved. No episodes of recrudescence have been noted in the year since initial presentation.

Treatment at a Glance

Cats infected with M haemofelis can be treated with pradofloxacin (5-10 mg/kg PO every 24 hours for 14 days)1,2,10 or doxycycline (5 mg/kg PO every 12 hours for 21 days).1,10

Pradofloxacin may offer a longer duration of bacterial clearance.10

In severe cases, glucocorticoids, transfusion, and IV fluids with glucose may be warranted.1,2

Discussion

Mycoplasma haemofelis is an unculturable bacterium that infects RBCs by attaching to the outer surface membrane.1,2 Formerly classified in the genus Hemobartonella, M haemofelis was reclassified as a Mycoplasma spp bacterium due to the similarity of the 16S rRNA gene sequence.1-3

The mode of transmission for M haemofelis is not well-established. Blood-sucking arthropods (eg, fleas) are reported to play a central role in transmission,4,5 but experimental evidence may be considered weak.2 Cats of any age can be infected, but younger male cats that roam outdoors and cats infected with FIV and FeLV are overrepresented.1,2,5 Horizontal transmission via cat bite is possible for both the biting and bitten cat,2 and abscesses may precede infection by a few weeks.6 In addition, although the exact mechanism is not understood, vertical (transplacental) transmission of M haemofelis may occur.2,7

Studies of experimental IV inoculation have demonstrated that after pathogen exposure, a preparasitemic phase occurs and typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks.7 Parasitemia follows and usually lasts 1 to 2 days and rarely beyond 4 days.7,8 During parasitemia, M haemofelis attaches to the RBC membrane, resulting in anemia due to extravascular erythrophagocytosis by macrophages in the spleen and other organs.8 In untreated patients that survive, clinical disease may last a month or longer, with several parasitemic episodes.7,8 Clinical episodes of M haemofelis parasitemia are often fatal if left untreated.1 Despite treatment and recovery, cats often become carriers for months to years, if not for life. Thus, low numbers of bacteria may still be observed occasionally. Stressful events and immunosuppression may trigger recrudescence and clinical disease.1,2,7,8

Clinical signs are attributed to the resulting hemolytic anemia and may include mucosal pallor, depression, fever, dehydration, icterus, tachypnea, weakness, anorexia, and splenomegaly.1,2 Abnormalities on CBC and blood smear typically include anemia, agglutination, and indicators of regeneration (eg, anisocytosis, macrocytosis, polychromasia, increased Howell–Jolly bodies, reticulocytosis).1,2 However, if anemia is peracute and the bone marrow has not had sufficient time to respond or cannot adequately respond due to underlying disease, the anemia may appear nonregenerative.2 Serum chemistry profile and urinalysis abnormalities are nonspecific and inconsistent; abnormalities may include bilirubinuria and hyperbilirubinemia secondary to extravascular hemolysis and increased ALT activity due to hypoxic injury with or without metabolic acidosis and prerenal azotemia.1 All cats with suspected M haemofelis infection should be tested for FIV and FeLV; ≈40% to 50% of cats with clinical hemotropic mycoplasmosis based on microscopic findings are FeLV positive.1

Although identification of M haemofelis via blood smear evaluation is a valuable diagnostic method, the bacterium is only present in sufficient numbers to enable microscopic identification in less than half of cases.1,2,7 Due to the intermittent parasitemia, molecular testing via PCR of the 16S rRNA gene is the test of choice to confirm diagnosis.1,2 In experimental infections, PCR yielded positive results 4 to 15 days postinfection and until appropriate antibiotic therapy was initiated.1,8 For feline carriers, PCR results are typically positive 3 days to 5 weeks after discontinuation of antimicrobial therapy.1 Although PCR is considerably more sensitive than identification on blood smear, it may produce a false-negative result if the number of bacteria is below the detection limit.2 The ACVIM consensus statement states that potential feline blood donors should test PCR-negative prior to being accepted into a blood donor program.9

Antimicrobial treatment can reduce the bacterial load and eliminate clinical signs but often does not clear the pathogen from the body.1 Tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are typically used.1,2,10 However, pradofloxacin may offer more effective long-term bacterial clearance than doxycycline and does not pose the same risk for retinal degeneration and blindness as does enrofloxacin.10 Thus, pradofloxacin was the therapy of choice in Carly’s case. Although not prescribed in Carly’s case, glucocorticoid therapy, in conjunction with antimicrobial treatment, may need to be considered for severely anemic patients to decrease erythrophagocytosis.1,2 In severe cases, supportive therapy (eg, blood transfusion) and IV fluids with glucose may be indicated.1,2

Take-Home Messages

M haemofelis was formerly classified as Hemobartonella.1,2

Cats of any age can be infected, but younger male cats that roam outdoors and cats infected with FIV or FeLV are overrepresented.1,2,5

M haemofelis can cause severe anemia that is usually regenerative but may be preregenerative if the bone marrow has not had time to respond or nonregenerative if underlying disease inhibits the response.1,2

The bacterium is not consistently found on routine blood smear, but a sensitive and specific PCR assay is available.1,2

All patients with suspected or confirmed M haemofelis should be tested for FIV and FeLV.1,2

Infected cats often become carriers with possible recrudescence during stress or illness.1

Cats should have a negative PCR screening test prior to being accepted into a blood-donor program.9