Providing care for therapy and assistance dogs can have significant legal, public health, and life-altering implications. Because these dogs have a public presence, it is essential to minimize disturbances and health risks to the public while also prioritizing the health and welfare of these dogs. The veterinary team is vital for the success of these human–animal partnerships, but exhaustive knowledge of a dog’s duties and training is not required for care; rather, understanding their roles, being aware of health risks, and supporting their well-being are key.

Ask the Expert: How are the unique welfare and medical needs of therapy and assistance dogs maintained?

Defining Roles

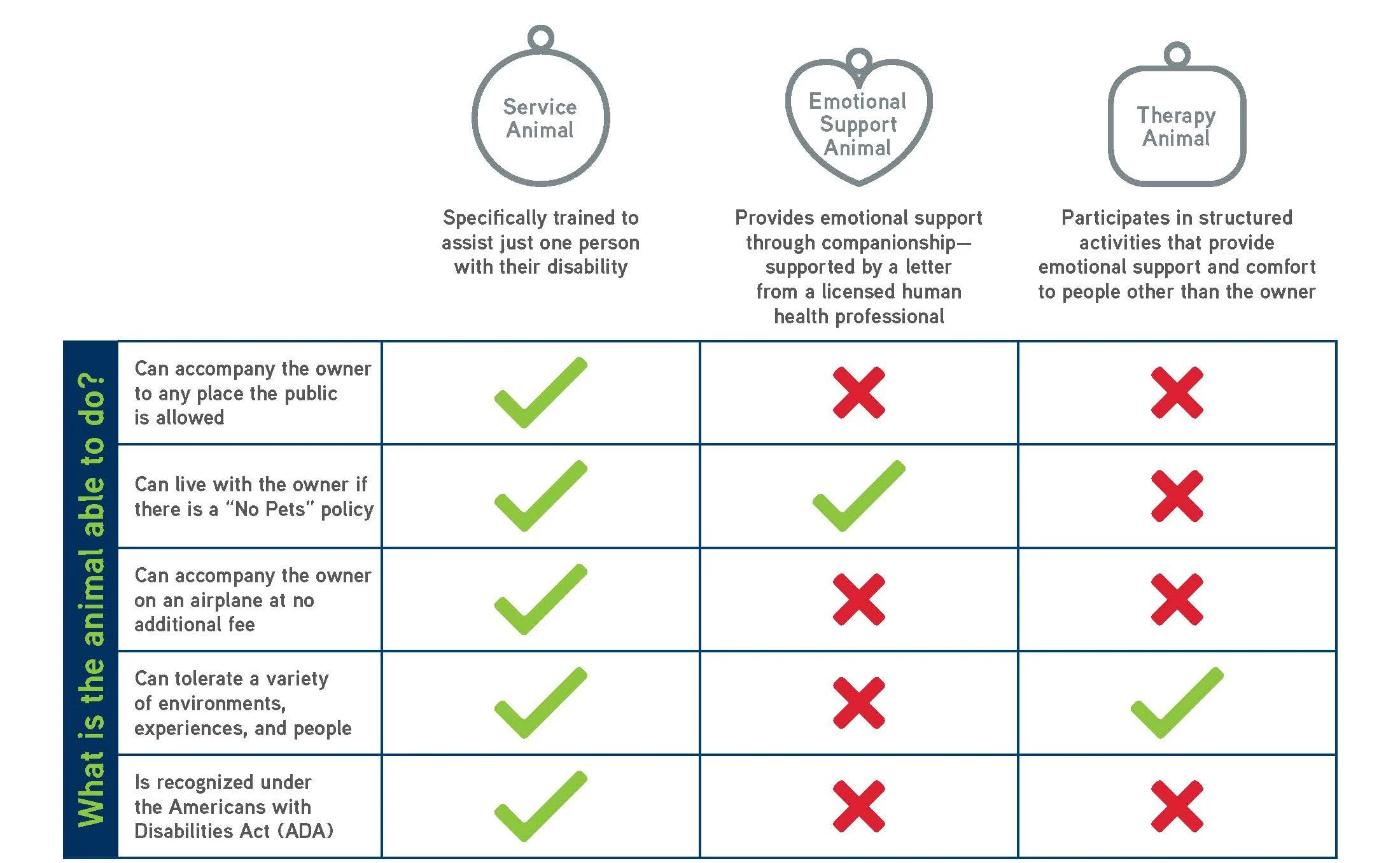

Recognizing and understanding the differences in the roles (ie, assistance, emotional support, therapy; Figure) of these patients is imperative to provide proper care. An assistance dog (ie, service dog) is trained to perform at least one task or behavior that helps alleviate the effects of a human disability. An emotional support dog lives with and provides emotional benefit for a human, as verified by an appropriately qualified health care professional. A therapy dog is trained to accompany humans on public visits to various locations, providing either general enjoyment and improvements in well-being or goal-oriented treatment.1

Visual indicators (eg, harnesses, identification badges) may offer insights into a dog’s role, but communication with the handler can provide precise information about the responsibilities of the role, whether the dog is required because of a disability, and the specific task the dog is trained to perform.

Illustration showing distinctions of support roles. Image used with permission from AVMA

The Initial Visit

During a patient’s first visit to the clinic, it is important to identify the affiliated organization, risks associated with daily activities, and accommodations needed for the patient or handler.

Organization Affiliation

Most assistance and therapy dogs are affiliated with a specific organization (emotional support dogs are typically not regulated by any governing organization). These organizations operate independently—often as nonprofits with distinct identities—and do not have universal guidelines to follow. Training and education requirements are set by each organization; therefore, registration, paperwork, and communication methods differ and can have significant implications for patient care, including how adverse effects can be managed and who assumes financial responsibilities. Establishing relationships with these organizations can help navigate intricacies of an individual patient’s care.

Risks & Responsibilities

Potential risks (eg, behavior toward humans, infectious disease) associated with a patient’s work should be explored. To understand risk factors that can affect the patient’s physical and mental stress and provide opportunities to enhance the patient's well-being, the handler should be asked questions regarding the patient’s daily life (see Common Questions for Assistance & Therapy Dog Handlers), including environments encountered, demographics of humans the patient engages with, and detailed responsibilities.

Common Questions for Assistance & Therapy Dog Handlers

Does the handler require special assistance during clinic appointments?a

What organization, if any, is the dog affiliated with?

Who maintains financial responsibility?a

If the dog is a service dog, is it required to help with a disability?a

What duties or tasks has the dog been trained to perform?a

Who does the dog help?a

What environments is the dog exposed to?

What is the frequency and method of transportation for the dog?

What special verbal or visual commands does the dog respond to?

What is used for positive reinforcement?

What type of diet is fed?

What equipment, if any, is used with the dog?

What animals is the dog exposed to?

What humans is the dog exposed to?

What are the dog’s working hours? How are breaks provided?

Does the dog consistently and reliably follow commands and perform tasks?

Does the dog display significant behavioral signs of stress (eg, excessive vocalizing, panting, yawning, lip-licking, pacing, freezing)?

How will the decision to retire the dog be made?

Do any barriers to routine care or treatment exist?

a Question intended for handlers of assistance dogs

Special Considerations

Assistance Dogs

Clinic facilities should be accessible to individuals with disabilities, including features like wheelchair ramps.2 Staff should be prepared and take proactive measures to assist handlers with special needs during appointments.

Therapy Dogs

Most therapy animal organizations request initial and annual health certification by a clinician to confirm the physical and behavioral well-being of dogs intended for therapy work. Certification often involves reviewing basic vaccination and preventive health history, as well as current medical conditions. Uncontrolled chronic diseases, conditions exacerbated by stress, resistant infections, and uncontrolled chronic pain may be contraindications for a dog’s duties. An impression of general behavior is also typically solicited. Determining behavioral suitability for therapy work is usually performed by the affiliated organization's behavioral evaluators, not the clinician.

Handling

Well-trained therapy and assistance dogs should respond promptly to commands and not display signs of aggression. Permission should be solicited prior to engagement in physical interaction with the dog to maintain training consistency and prior to separation from the handler if the dog serves in a medical capacity (eg, seizure alert). The handler can provide specific cues and commands that can be used during the appointment.

Well-trained dogs may still exhibit signs of fear, anxiety, and stress in the clinic. Using patient-centered handling techniques can help alleviate these signs. Treats given for positive reinforcement should be approved by the handler. If sedation is recommended, details, including the expected duration of effect that may influence the dog’s ability to work, should be discussed with the handler.

Preventive Care

Guidelines for preventive care should align with a patient’s life stage.3 Detecting minor health issues early is crucial for maintaining health and functionality. Physical examinations, along with diagnostic evaluations (eg, blood work, fecal tests, urinalysis as needed), should be performed twice per year.

Vaccines should be given in accordance with current local recommendations.4 If exposure is possible, vaccination against leptospirosis and minimizing leptospiruria is recommended due to zoonotic risk, particularly in dogs that will be in contact with immunocompromised humans.5,6

Special Considerations

Assistance Dogs

Proactive measures to prevent obesity and musculoskeletal issues, including osteoarthritis, and regular exercise to maintain fitness should be discussed with the handler. The fit of equipment worn while working should be assessed and adjusted as needed.

Health of systems essential for a dog’s function (eg, dental health in assistance dogs that use their mouths, musculoskeletal system in mobility dogs, vision health in guide dogs) should be closely monitored. Some veterinary ophthalmologists may offer complimentary screening for working dogs.

Screening blood work may hold greater significance for working dogs, enabling earlier detection of subclinical disease, which can facilitate prompt diagnosis and treatment and potentially lead to improved outcomes.3 One study found older assistance dogs with elevated ALT had shorter lifespans,7 indicating a need for assertive diagnostic and therapeutic interventions when increased ALT is detected.

Therapy Dogs

Handlers should be educated that consistent handwashing can help prevent zoonotic disease. Microscopic fecal examination for parasites, especially those that are common and zoonotic (eg, Ancylostoma spp, Toxocara spp), should be conducted every 6 to 12 months; however, routine screening for other zoonotic organisms (eg, group A streptococci, Clostridium difficile, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) is not recommended because a negative result may provide a false sense of security (as infection can occur later or the test may not detect low shedding), and a positive result in a clinically normal dog may not warrant treatment.8 A positive result may indicate clinically insignificant contamination or self-limiting infection, and administering antibiotics unnecessarily could cause more harm.

Accurate diet history should be obtained to assess risk for zoonotic disease transmission, as dogs fed raw meat-based diets can have increased shedding of Salmonella spp and Escherichia coli.9 Dogs fed raw meat-based diets, including chews or treats, within the previous 90 days should not be permitted to work as therapy dogs, particularly in hospital settings.10 Some organizations may strictly prohibit dogs fed raw meat-based diets or other raw animal-based products (eg, rawhides, other dehydrated treats).

Oral preventives may be preferable to avoid residue from topical products on the coat.

Medical Considerations

Handlers should be advised to seek veterinary attention at the onset of any signs of illness, and the clinic should provide prompt accommodation and prioritization. Pet insurance may be recommended for handlers who are financially responsible for their dog to help pay for emergency services and potentially eliminate delays in veterinary care caused by financial constraints.

Possible effects of medication on performance (particularly sedation or behavior changes), as well as those that increase thirst, urination, hunger, and defecation, should be discussed with the handler.

A well-defined plan for returning to work should be outlined for dogs with medical limitations, especially dogs unable to work due to their health status or prescribed medications. A break that extends one week past resolution of clinical signs may be advisable, with a recommended recheck evaluation before work is resumed.

Special Considerations

Assistance Dogs

Communication is key if a dog is affiliated with an organization that retains financial responsibility and authority over medical decisions.

Handlers may have difficulty complying with certain medical recommendations (eg, dividing pills, opening packages, performing physically intensive treatments [eg, bathing, ear cleaning]). Alternative options may be necessary.

Unique and rare adverse effects of medications can reduce a dog’s ability to perform certain functions. For example, metronidazole can impair olfaction in working dogs and thus may need to be avoided in assistance dogs (eg, diabetic alert dogs) that rely on scent detection.11

Therapy Dogs

Dogs with conditions that require treatment (eg, antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy) that may pose risks for humans in direct contact with the dog should stop working until treatment is complete and the condition resolved.

Retirement

Therapy and assistance dogs have a finite amount of time they can work. Determining when these dogs should retire can be difficult, but they should not be expected to work until the end of their lives. Handlers should be educated on how to identify physical and behavioral cues that indicate health challenges and how to regard the dog’s quality of work life objectively, maintaining the dog’s welfare as top priority. Tools to assess quality of work life should include sociability, enthusiasm for work, playfulness, energy level, rest, mobility, appetite, predictable eliminations, obedience, and frequency of displays of stress.12

Transition to retirement should be based on the individual dog, as abrupt cessation of work can have negative implications for the dog and handler. A gradual transition can be considered.

Special Considerations

Assistance Dogs

Guide dogs typically have an average working span of 8 years, with premature retirement most commonly attributed to musculoskeletal and neurologic disorders.13 Careful evaluation should be conducted for any condition that results in chronic pain, as painful conditions can detract from work, heighten agitation, and trigger biting incidents, thereby warranting consideration for retirement.

Assistance dogs perform essential daily functions, and retirement of these dogs can be life-altering for the dog and handler. Inquiring about the handler's plans for the dog after retirement and how they plan to transition to a new assistance dog can provide valuable insights and opportunities for support.

Therapy Dogs

Retirement of a therapy dog can have a significant impact on the handler. Some handlers take considerable pride in working with their therapy dog and engaging in volunteer activities, which can lead to bias when determining whether the dog should continue working when retirement may be more appropriate.

Conclusion

A thorough understanding of the needs of therapy and assistance dogs and their handlers allows the veterinary team to help these dogs fulfill their unique roles and ensure the safety and welfare of the dogs and their handlers.