Respiratory Distress & Inappetence in a Border Collie

Kursten Pierce, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology), Colorado State University

We sat down with Dr. Pierce to further discuss the connection between boutique diets and dilated cardiomyopathy. Listen to her episode of Clinician's Brief: The Podcast here.

Nora, a 3-year old, 41.1-lb (18.7-kg) spayed border collie crossbreed, was presented on an emergency basis for respiratory distress and inappetence of 48 hours’ duration. The owner reported a cough that had developed and progressively worsened, as well as a decrease in appetite and activity, over the previous month. In the 48 hours prior to presentation, Nora had also become reluctant to go on her regular daily walks. The owner additionally reported loss of muscle mass and noted that, in the few days before presentation, Nora had seemed uncomfortable with an abdominal breathing component and that respiratory rate and effort had progressively increased.

Nora had been fed 3 cups of a grain-free dry kibble diet per day since adoption from a shelter 2.5 years previously. The diet’s main ingredients included kangaroo, kangaroo meal, chickpeas, peas, and lentils. Additional dietary history included occasional freeze-dried liver treats (maximum, 2-3 per week) from a local pet store and no human food. She was not receiving any vitamins, supplements, or medications other than her monthly parasite preventive. Nora was considered an otherwise healthy dog, had no travel history since adoption, and was up-to-date on flea, tick, and heartworm preventives.

Physical Examination

On presentation, Nora was quiet but alert and responsive and had a BCS of 3/9 and mild muscle wasting. She was moderately dyspneic and tachypneic, with a resting respiratory rate of 60 breaths per minute. She had weak femoral pulses (200 bpm), was normothermic (100.3°F [37.9°C]), and had light pink mucous membranes, with a capillary refill time of 2 seconds. Jugular venous distension was observed. Cardiac auscultation revealed tachycardia with a regular rhythm and a grade II/VI left apical systolic heart murmur. Harsh bronchovesicular sounds and crackles were auscultated. Because of concern for congestive heart failure (CHF), furosemide (2 mg/kg IV) was administered, the patient was placed in an oxygen cage, and a cardiac consultation was conducted.

Diagnosis

Initial CBC and serum chemistry results were normal, with the exception of hyperlactatemia (blood lactate, 3.8 mmol/L; reference range, 0.20-1.44 mmol/L). Blood lactate concentration is a measure of anaerobic metabolism. Hyperlactatemia can occur secondary to decreased oxygen delivery (eg, volume depletion, blood loss, cardiogenic or septic shock), increased oxygen demand (eg, seizures, exercise), inadequate oxygen utilization (eg, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis), and/or drugs or toxins.1 Hyperlactatemia in this patient was suspected to be due to hypoperfusion secondary to active CHF and systolic dysfunction.

Nora was hypotensive and had a systolic blood pressure of 85 mm Hg obtained via Doppler from the left dorsal metatarsal with the patient in right lateral recumbency. ECG revealed sinus tachycardia with a heart rate ranging from 186 to 210 bpm. No ectopic beats were visualized on 6-lead ECG or telemetry.

An echocardiogram and thoracic radiographs were obtained. The echocardiogram revealed decreased left ventricular (LV) wall thickness, severe dilation of the LV chamber (ie, eccentric hypertrophy), and severely reduced LV systolic function. Severe left atrial enlargement with a moderate degree of centrally directed left atrioventricular valve regurgitation (suspected functional) was observed. The left atrioventricular valve leaflets appeared normal in thickness with poor coaptation due to annular stretch. In addition, there was mild dilation of the right atrium and ventricle with a mild degree of right atrioventricular valve regurgitation. Results of echocardiography were consistent with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM; Figures 1-4).2,3

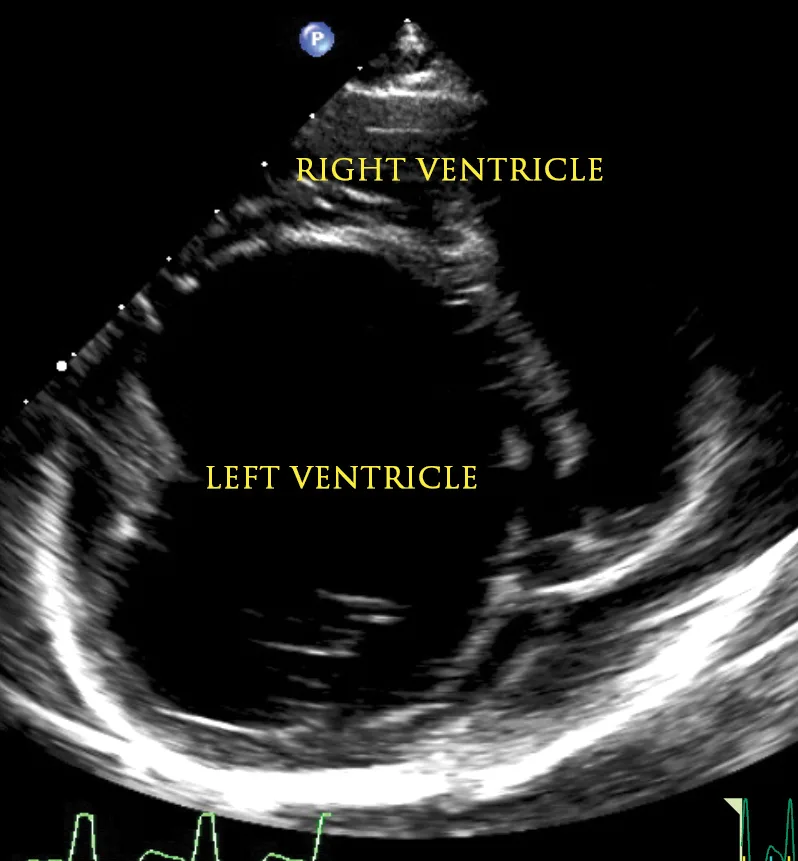

Figure 1

2D echocardiographic image of the left ventricle from the right parasternal short axis view. There is decreased thickness of the LV walls and severe dilation of the LV cavity consistent with DCM.

Thoracic radiographs (Figures 5 and 6) revealed marked cardiomegaly with a globoid cardiac silhouette and severe left atrial enlargement. Pulmonary venous congestion and an interstitial pulmonary pattern in the perihilar and caudal lung fields were consistent with cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Because of the patient’s dietary history of being fed a grain-free diet for the last 2.5 years and concern for diet-associated DCM, whole blood and plasma taurine levels were evaluated and found to be normal (plasma taurine, 112 nmol/mL; reference range, 60-120 nmol/mL: whole blood taurine, 262 nmol/mL; reference range, 200-350 nmol/mL).4 Cardiomyopathy secondary to taurine deficiency has been reported in golden retrievers5-7 and cocker spaniels, which are taurine- and L-carnitine–responsive breeds.7,8 Grain-free diets have been linked to DCM in patients with normal taurine levels, suggesting an alternative mechanism in the development of DCM. Potential mechanisms are under investigation. DCM may be suspected based on dietary history, breed (ie, atypical breed for DCM, lack of familial history, breed predisposition), and the elimination of other underlying causes (ie, myocarditis, toxicity, tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy).

DIAGNOSIS:

DIET-ASSOCIATED DILATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

Want to hear more?

Treatment & Long-Term Management

Cardiac medications for management of CHF and systolic dysfunction, including furosemide (2.14 mg/kg PO q12h), pimobendan (0.27 mg/kg PO q12h), and enalapril (0.53 mg/kg PO q12h), were initiated. Taurine (26.7 mg/kg PO q12h) was added as a supplement due to concern for diet-associated DCM. Because the exact mechanism of diet-associated DCM is not well understood and taurine has been shown to be beneficial for cardiovascular disease (ie, antioxidant effects, protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury, modulation of intracellular calcium concentrations), taurine supplementation was continued in this patient. Nora was transitioned to a commercial, nonboutique, nonexotic protein, nongrain-free diet (see Treatment at a Glance).

Nora was presented for a recheck examination with thoracic radiography, renal values with electrolytes, and blood pressure 10 days after starting cardiac medications. Results of the subsequent testing revealed adequate control of CHF and radiographic resolution of pulmonary edema. Nora was eupneic (resting respiratory rate, 20 breaths per minute) and normotensive (systolic blood pressure, 115 mm Hg). Coughing had resolved, and serum chemistry results showed no evidence of azotemia or electrolyte derangements.

TREATMENT AT A GLANCE

The patient should be transitioned to a commercial, nonboutique, nonexotic protein, nongrain-free diet with standard ingredients manufactured by an established company.9,11-13,15

Taurine should be supplemented if the patient has confirmed or suspected taurine deficiency.4,5,9,11,13

Based on echocardiography, medications such as pimobendan and ACE inhibitors may be prescribed to support cardiac function, decrease preload, and inhibit the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

If CHF is present on thoracic radiographs, therapy should be instituted with diuretics, pimobendan, and ACE inhibitors or other cardiac medications as indicated based on echocardiography.3,17,18

Additional therapies (eg, antiarrhythmic drugs) may be recommended if an arrhythmia has been documented.

Outcome

Nora was presented for a recurrence of CHF, dyspnea, and coughing a month after the recheck examination and responded to up-titration of diuretic therapy. At the 3-month recheck after initial presentation (ie, 2 months after presentation for recurrence), CHF and systolic dysfunction were stable.

Discussion

DCM can be idiopathic, genetic, and/or primary. DCM can also occur secondary to infectious disease (eg, myocarditis, parvovirus in puppies, Chagas disease), toxicity (eg, doxorubicin-induced), or nutritional causes (eg, taurine or L-carnitine deficiency, diet-associated) or can be tachycardia-induced/mediated (eg, myocardial failure due to persistent tachyarrhythmias).3,9 Inherited DCM has been reported in large- and giant-breed dogs (eg, Doberman pinschers, Great Danes, Irish wolfhounds).2,3,10

In July 2018, the US FDA released a notice regarding reports from veterinary cardiologists of suspected diet-associated DCM in dogs not typically predisposed to DCM. Since then, the FDA has released an additional update on their investigation, reporting over 300 dogs with suspected diet-associated DCM as of November 2018.11 Diets of concern include pet foods containing peas, lentils, fava beans, tapioca, barley, chickpeas, other legume seeds, and potatoes as the main ingredient and/or exotic ingredients (eg, kangaroo, duck, buffalo, bison, venison).9,11 Pet food from boutique companies (ie, small manufacturers) that contain exotic ingredients (eg, nontraditional protein sources) and/or are grain-free are also suspected to be linked to diet-associated DCM.9,12-14 See Suggested Reading for a resource providing additional information and updates on these diets and their association with DCM.12,13 It is important to note that diets that meet minimum nutrient standards and that are formulated based on Association of American Feed Control Officials recommendations do not necessarily ensure a balanced or regulated diet. There have been no documented cases of diet-associated DCM in dogs eating a commercial diet from an established major pet food company. Pet foods should ideally undergo feeding trials to verify complete and balanced nutrition.15

DCM has also reportedly been diagnosed in a few subsets of dogs, including primary DCM in predisposed breeds (unrelated to diet), diet-associated DCM in dogs with normal taurine levels, and diet-associated DCM in dogs with taurine deficiency (eg, golden retrievers).5,9,11,13 A previous study demonstrated that dogs with DCM that were fed a grain-free diet had a greater magnitude of LV dilation on echocardiography as compared with dogs with DCM that were fed a nongrain-free diet.14 The exact mechanism for the development of DCM in dogs fed these diets is not completely understood and may be multifactorial.9,11-14,16 Theorized causes under investigation include reduced bioavailability of nutrients due to interactions with other ingredients, nutrient deficiencies, and potential for cardiotoxic ingredients.9

Recommendations for treatment and additional diagnostics vary by patient but may include obtaining a detailed dietary history,9,11-13,15 evaluating whole blood and plasma taurine levels,4 providing taurine supplementation, screening for DCM via echocardiography, initiating cardiac medications as indicated,5,9,11-13 and transitioning the patient to a nonboutique, nonexotic protein, nongrain-free diet with standard ingredients and manufactured by an established company (see Take-Home Messages and Suggested Reading).9,15 Additional diagnostics (eg, ECG, 24-hour Holter monitoring, thoracic radiography, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide, troponin levels) may be suggested based on cardiac evaluation. The specific diet of patients with suspected diet-associated DCM should be reported to the FDA.9,11 Owners of dogs with diet-associated DCM should be questioned if other pets in the household are eating the same diet.

The subclinical occult phase of DCM can last up to 2 to 4 years, whereas median survival time in dogs with development of CHF secondary to primary DCM is reportedly 6 to 12 months.3,17,18 Follow-up echocardiography should be recommended every 3 to 6 months to monitor for improvement. Reverse remodeling may be visualized in some patients in this timeframe, whereas others may take longer (ie, 6-9 months) or show no improvement.9,11,13 For example, a study has shown golden retrievers with taurine deficiency and DCM to have slow and steady improvement over a 6- to 12-month period after diet was changed and taurine supplementation was initiated. Of the 11 dogs with CHF in this study, 9 had resolution of congestion, and 5 were tapered off diuretics completely.5

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

A detailed dietary history should be obtained in all patients suspected of having DCM. Diet changes should be recommended if the patient is being fed a diet of concern for diet-associated DCM.9,12-14

Evaluating plasma and whole blood taurine levels, as well as initiating taurine supplementation, should be considered. Taurine should be supplemented until levels are normal and in cases in which the owner declines to submit taurine levels due to financial constraints.

If a patient is being fed a diet of concern and is experiencing cardiac clinical signs (eg, dyspnea, tachypnea, coughing, exercise intolerance, syncope), a full cardiac diagnostic investigation, including echocardiography, is recommended to evaluate for possible diet-associated DCM.

Any suspected or documented cases of diet-associated DCM should be reported to the FDA.11

CHF = congestive heart failure, DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy, LV = left ventricular