Recurrent Pruritus & Zoonotic Potential

This article is part of the One Health Initiative

Olive, a 4-year-old, spayed Labrador retriever, was presented for evaluation of pruritus.

HistoryOlive had a history of seasonal atopy and had presented with superficial bacterial folliculitis (SBF) at approximately the same time each of the past 2 years. She had not been treated since receiving cephalexin at her presentation the previous year.

Examination, Diagnostic Testing, & Treatment

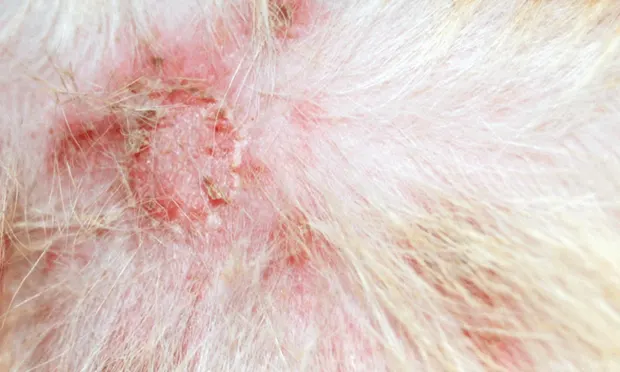

At presentation, Olive was overweight but appeared clinically normal except for disseminated skin lesions (Figure 1). Erythematous papules and pustules were present, particularly over the ventral abdomen. Areas of self-induced trauma were noted. Cytology of a pustule sample revealed abundant intracellular cocci and inflammatory cells (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Focal staphylococcal folliculitis caused by MRSP. Courtesy Dr. B. Valentine

Daily bathing in 2% chlorhexidine was recommended pending culture results for the same pustule sample. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) was isolated (Table). During a phone call to receive test results, the owners reported that Olive’s pruritus had improved significantly with bathing. Continuing topical chlorhexidine treatment 2 to 3 times weekly and a recheck in 10 to 14 days was recommended (ideally, bathing would continue until 7 days after resolution of signs). However, the owners called back after researching MRSP on the Internet; they were particularly concerned for their 6- and 10-year-old children.

Figure 2. Cytologic appearance of superficial bacterial folliculitis. Note the inflammatory cells and engulfed cocci.

Ask Yourself: Which of the following statements is true?

A. MRSP is a canine pathogen that does not infect humans.

B. MRSP is a rare human pathogen, so the owners should not be concerned.

C. MRSP is a rare human pathogen, but pet owners should use basic hygiene and infection control measures to lower their risk for infection.

D. MRSP is an uncommon human pathogen, but infected dogs should be treated with systemic antibiotics to ensure that the infection is rapidly eliminated.

E. MRSP is a concern particularly for children, so the dog should be strictly isolated at home, handled only by adults, and not allowed outdoors.

F. MRSP is a concern for adults and children, so infected dogs should be hospitalized until test results are negativefor MRSP.

Related Article: 5 Things Veterinarians Should Know About Methicillin-Resistant Infections

Correct AnswerC. MRSP is a rare human pathogen, but pet owners should use basic hygiene and infection control measures to lower their risk for infection.

Internationally, MRSP diagnosis in dogs is increasingly common and has become a common cause (and in some geographic locations, the leading cause) of opportunistic infections in dogs, particularly skin and surgical site infections.1-4 As with other methicillin-resistant staphylococci, MRSP is inherently resistant to all β-lactam antimicrobials (eg, penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems) and is often resistant to multiple other antimicrobials. MRSP is commonly highly drug resistant with few viable antimicrobial options,3,5 thereby complicating treatment.

Most dogs that harbor MRSP do so without any disease signs and probably never develop an infection. However, healthy carriers are at risk for subsequent MRSP infection and are a potential source of infection for other dogs (or, rarely, humans).

MRSP can be transmitted between animals, particularly housemates. A dog that lives with an MRSP-infected dog is likely to become a carrier. Whether anything can be done to minimize risk is unclear. By the time MRSP is diagnosed, the other dog will already have been exposed. Strict isolation of infected dogs can be challenging in multidog households, making it difficult to recommend aggressive practices that lower the risk for MRSP transmission between cohabitating dogs.

Similarities exist between MRSP in dogs and methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) in humans. Albeit uncommon and transient, cross-species transmission of both pathogens can occur.6-8 S pseudintermedius colonization, including colonization with MRSP, can typically be found in less than 5% of healthy humans (mainly pet owners and veterinarians).5-7,9-11

Related Article: Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcal Infections

In addition to colonization, S pseudintermedius can cause clinical infections in humans, but these are rare and often misidentified as S intermedius.12-14 Considering the high prevalence of S pseudintermedius in healthy dogs and large percentage of the population with regular canine contact,15 the rarity of human infections indicates that this bacterium is poorly able to infect humans. Few reports of human MRSP infections exist,14,16 and while more infections have probably occurred than have been published, evidence that MRSP infections are anything but rare in humans is lacking. In addition, because there is no evidence that MRSP is more likely to cause an infection than is methicillinsusceptible S pseudintermedius, little evidence suggests that increasing MRSP rates in dogs will result in increasing human infections.

Despite this rarity, basic measures to reduce human exposure are indicated to prevent potential infection, as MRSP is typically highly drug resistant (ie, while infections are unlikely, they can be difficult to treat). Strict isolation is neither practical nor typically necessary. The use of basic hygiene practices (eg, good attention to hygiene after contact with the dog, limiting contact with the dog, avoiding contact with body sites where MRSP is common [eg, infected skin, nose, mouth, perineum]) is practical and may reduce risk for dog-to-human transmission. Recommending that children not help with bathing, that bathing be done outdoors if possible, and that those who bathe the dog wash their hands and change their clothes afterward is reasonable.

Systemic antimicrobial therapy is not always required for MRSP infections, and topical therapy and addressing identifiable underlying causes can be an effective approach for S pseudintermedius SBF.17,18

MRSP = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, SBF = superficial bacterial folliculitis

The Take-Home

MRSP is increasingly common in dogs, particularly those with pyoderma.

Although MRSP can infect humans, infections are rare and the risk posed by an infected dog is low.

Basic hygiene practices are easy to implement in a household and can likely reduce the risk for zoonotic transmission of MRSP and similar pathogens.

J. SCOTT WEESE, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM, is a veterinary internist and microbiologist, is chief of infection control at University of Guelph Ontario Veterinary College Health Sciences Centre, and holds a Canada Research Chair in zoonotic diseases. Dr. Weese’s research foci are infectious and zoonotic diseases (particularly of companion animals), infection control, staphylococcal infections, Clostridium difficile infection, and antimicrobial therapy.

RECURRENT PRURITUS & ZOONOTIC POTENTIAL • J. Scott Weese

References

1. Prevalence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcuspseudintermedius (MRSP) from skin and carriage sites of dogs after treatment of their meticillin-resistant or meticillin-sensitive staphylococcal pyoderma. Beck KM, Waisglass SE, Dick HLN, Weese JS. Vet Dermatol 23:369-375, 2012.2. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from healthy dogsand dogs affected with pyoderma in Japan. Onuma K, Tanabe T, Sato H. Vet Dermatol 23:17-22, 2012.3. Clonal spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Europe and North America: An international multicentre study. Perreten V, Kadlec K, Schwarz S, et al. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1145-1154, 2010.4. Post-hospital discharge procedure-specific surgical site infection surveillance in small animal patients. Turk R, Singh A, Weese J. 2nd ASM/ESCMID Conference on Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococci in Animals, 2011.5. Sharing more than friendship—Nasal colonization with coagulase-positive staphylococci (CPS) and co-habitation aspects of dogs and their owners. Walther B, Hermes J, Cuny C, et al. PLoS ONE 7:e35197, 2012.6. Risk of colonization or gene transfer to owners of dogs with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Frank LA, Kania SA, Kirzeder EM, et al. Vet Dermatol 20:496-501, 2009.7. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius between infected dogs and cats and contact pets, humans and the environment in households and veterinary clinics. van Duijkeren E, Kamphuis M, van der Mije IC, et al. Vet Microbiol 150:338-343, 2011.8. Longitudinal study on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in households. Laarhoven LM, de Heus P, van Luijn J, et al. PLoS ONE 6:e27788, 2011.9. High diversity of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius lineages and toxigenic traits in healthy pet-owning household members. Underestimating normal household contact? Gómez-Sanz E, Torres C, Lozano C, et al. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 36:83-94, 2013.10. Carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in small animal veterinarians: Indirect evidence of zoonotic transmission. Paul NC, Moodley A, Ghibaudo G, et al. Zoonoses & Public Health 58:533-539, 2011.11. The prevalence of carriage of meticillin-resistant staphylococci by veterinary dermatology practice staff and their respective pets. Morris DO, Boston RC, O’Shea K, et al. Vet Dermatol 21:400- 407, 2010.12. Metastatic complications from Staphylococcus intermedius, a zoonotic pathogen. Hatch S, Sree A, Tirrell S, et al. J Clin Microbiol 50:1099-1101, 2012.13. Staphylococcus intermedius—rare pathogen of acute meningitis. Durdik P, Fedor M, Jesenak M, et al. Int J Infect Dis 14 Suppl 3:e236-238, 2010.14. Beware of the pet dog: A case of Staphylococcus intermedius infection. Kempker R, Mangalat D, Kongphet-Tran T, et al. Am J Med Sci 338:425-427, 2009.15. Household knowledge, attitudes and practices related to pet contact and associated zoonoses in Ontario, Canada. Stull JW, Peregrine AS, Sargeant JM, et al. BMC Public Health 12:553, 2012.16. Human infection associated with methicillinresistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius ST71. Stegmann R, Burnens A, Maranta CA, et al. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:2047-2048, 2010.17. Comparison of a chlorhexidine and a benzoyl peroxide shampoo as sole treatment in canine superficial pyoderma. Loeffler A, Cobb MA, Bond R. Vet Rec 169:249, 2011.18. Efficacy of a surgical scrub including 2% chlorhexidine acetate for canine superficial pyoderma. Murayama N, Nagata M, Terada Y, et al. Vet Dermatol 21:586-592, 2010.