This response is correct!

Radiographic Interpretation of the Canine Shoulder

Ryan King, DVM, DACVR, Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University

Stacie Aarsvold, DVM, DACVR, Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University

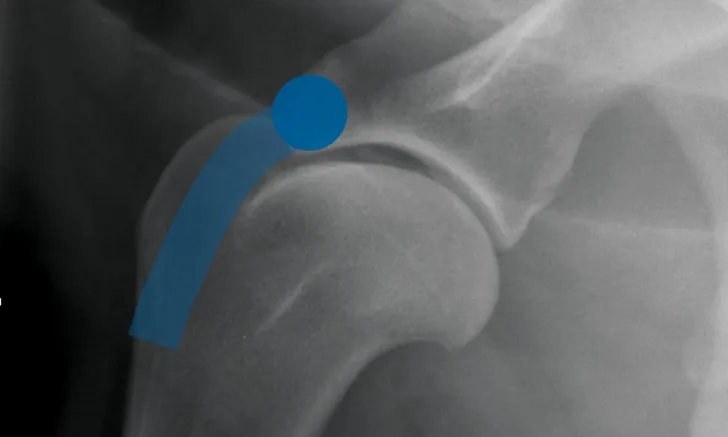

Lateral radiograph of a normal shoulder showing the biceps origin (blue circle) and course (blue bar)

Shoulder lameness is common in juvenile and adult dogs. Lameness may be caused by degenerative, infectious, neoplastic, or developmental growth disorders. Radiographically identifying lesions can help clinicians categorize associated conditions.

A complete radiographic series, including lateral, caudocranial +/- cranioproximal–craniodistal oblique (skyline) views, should be obtained when evaluating patients with shoulder lameness. Accurate diagnosis requires radiographs that are correctly positioned and exposed. Sedation is recommended for patients undergoing orthopedic radiography.

Anatomy

Before radiography, the clinician should review the anatomy of the canine shoulder. The shoulder consists of a simple ball-and-socket joint between the humeral head and the glenoid cavity and is surrounded by a fibrous joint capsule. The adjacent musculature stabilizes the joint and extends and/or flexes the thoracic limb. The joint is extended by the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles and flexed by the triceps muscle, with concurrent flexion and extension of the elbow by the biceps and triceps muscles, respectively.1

The proximal biceps tendon originates from the supraglenoid tubercle and traverses the cranial aspect of the proximal humerus in the intertubercular groove, where, at the musculotendinous junction, it forms the biceps muscle. Mineralization may occur at any point along the length of the tendon but is commonly noted both superimposed with the groove and at the tendon origin (Figure 1).1

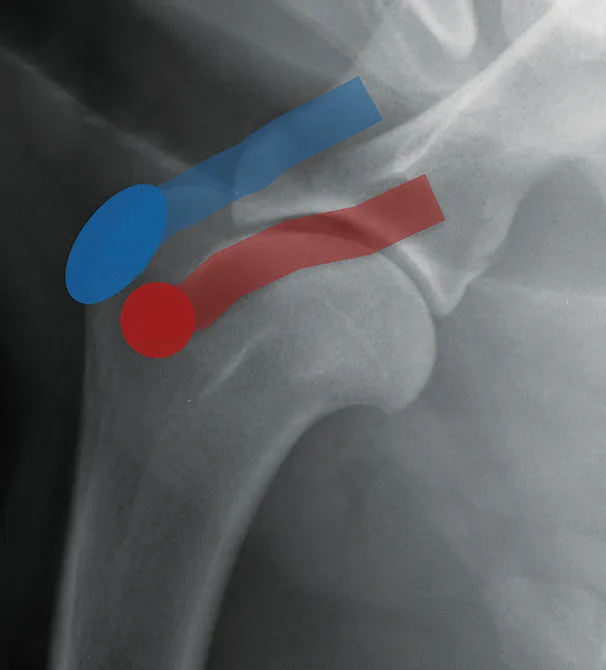

Lateral radiograph of a normal shoulder showing the supraspinatus insertion (blue oval) and tendon course (blue bar) as well as the infraspinatus insertion (red circle) and tendon course (red bar)

The supraspinatus tendon is a broad tendon that arises from the supraspinatus muscle and is attached to the lateral aspect of the greater tubercle. Tendinopathy of this tendon is common and manifests radiographically as mineralization within the tendon, typically slightly cranial to the greater tubercle. The infraspinatus tendon is affected less commonly. This tendon arises from the infraspinatus muscle and attaches on the lateral greater tubercle, slightly distolateral to the supraspinatus tendon, and runs in an oblique plane in a caudoproximal-to-craniodistal direction (Figure 2).1

Common Diseases

Tendinopathies typically occur in older, active, and working dogs, typically of large breeds. Pain usually can be elicited on flexion, extension, and palpation of the shoulder. Disease occurs most commonly in the proximal biceps and supraspinatus tendons but can also affect the infraspinatus tendon (Table).

Common Diseases of the Canine Shoulder

The most common site of osteochondrosis in dogs is the caudal aspect of the humeral head. Osteochondrosis typically occurs in young (<3 years of age), large-breed dogs and appears radiographically as a flattening of the caudal humeral head. A free mineral fragment may be visualized near the flattened region or more distally in the joint capsule. Free fragments are rarely seen in the intertubercular groove.

Osteochondritis dissecans is a disease that affects young dogs in which failure of endochondral ossification leads to retention and thickening of cartilaginous tissue. The cartilage may form a flap and/or free fragments in the joint.

Degenerative joint disease affects the entire joint, but the caudal humeral head is a common site of osteophytosis development. Degenerative joint disease appears radiographically as well-defined, irregularly shaped new bone formation on the caudal aspect of the glenoid cavity or the caudal humeral head. In many dogs, a small, separate, triangular center of ossification may be present and associated with the caudodistal scapula (caudal glenoid cavity; Figure 3).2 This should not be confused for degenerative joint disease.

Lateral radiograph of a mature shoulder with a separate center of ossification in the caudodistal scapula (black arrow). Minimal osteophytosis of the caudal aspect of the humeral head (white arrow) is also present.

Less common diseases should be considered when the presentation is not straightforward. The proximal humerus is a common site for osteosarcoma. On radiographs, its appearance is highly variable, but the classic presentation shows moth-eaten–to–permeative lysis of the cortex with palisading-to-amorphous new bone formation, often along the caudal cortex. Any lesion with a lytic component in the proximal humerus should be considered suggestive of osteosarcoma. Metastatic disease more commonly appears as lesions within the metaphysis of long bones, such as near the nutrient foramen.

Infectious/septic arthritis of the shoulder joint is an uncommon disease that typically affects young, large-breed dogs. These patients often have a predisposing cause for systemic sepsis. Radiographs often show a patchy pattern of lucencies (from gas-producing bacteria) superimposed on the joint and surrounding tissues. Staged sampling of periarticular tissues should precede arthrocentesis to avoid bacterial contamination of the joint capsule.

Traumatic shoulder luxations are uncommon and are typically diagnosed on physical examination. A caudocranial radiograph with the limb in abduction can be obtained to identify medial joint capsule tearing. This radiograph must be interpreted with caution, however, as some degree of joint widening may be normal secondary to positioning because limb extension causes traction on the medial aspect of the joint.