Step-by-Step Guide to Performing Pericardiocentesis

April L. Paul, DVM, DACVECC, Tufts University

Pericardiocentesis is performed in animals diagnosed with clinically significant pericardial effusion. Considered an emergency procedure in animals, it is associated with cardiac tamponade in which cardiac output is limited. Most dogs with pericardial effusion are large-breed dogs. The most common cause of pericardial effusion is neoplasia, although other causes, (eg, infection, vitamin K antagonist rodenticide intoxication, restrictive pericarditis) are possible. In rare cases, pericardial effusion is idiopathic.

Diagnosis

Clinical signs include collapse, muffled heart sounds, pulsus paradoxus (ie, an exaggerated decrease in systolic blood pressure during inspiration) or weak pulse, tachycardia, and tachypnea. Jugular venous distension may be appreciated. Abdominal effusion from right heart failure or, less commonly, from concurrent hemoabdomen may also be present.

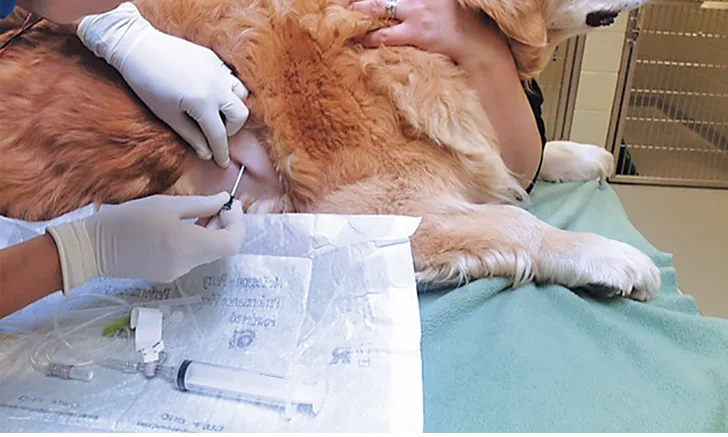

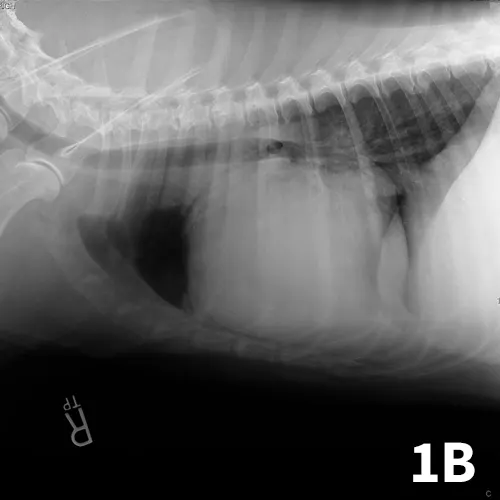

Diagnosis may be based on clinical signs, thoracic radiographs documenting a globoid cardiac silhouette (Figure 1), or ultrasonography (Figure 2). If possible, a complete cardiac ultrasound examination should be performed before pericardiocentesis, as the effusion will help delineate a mass.

Ventrodorsal (A) and right lateral (B) thoracic radiographs showing a globoid heart.

Pericardial effusion on ultrasonography

Before performing pericardiocentesis, it is important to discuss with owners the possible complications, which include ongoing bleeding, severe ectopy, cardiac arrest, and death. Without pericardiocentesis, however, death is usually imminent.

Before the Procedure

The patient should be placed in left lateral or sternal recumbency. Pericardiocentesis is typically performed from the right side to decrease the risk for lacerating a major coronary artery. Some patients require light sedation; for others, local anesthesia is adequate. If the practitioner has not performed many pericardiocentesis procedures, or if the patient is active or anxious, sedation is recommended.

The planned site must be selected before the procedure. Ultrasonography is ideal to determine a location with adequate visualization of the heart and effusion; if ultrasonography is unavailable, the best location can be determined by feeling for the strongest palpable heartbeat, as there will be less interference from the lungs. Alternatively, the fifth intercostal space at the costochondral junction, found by pulling the patient’s right forelimb caudal to 90° flexion and locating the point of the elbow, can generally be used. The lateral aspect of the right thorax should be clipped over the area where the heart can be palpated.

Electrocardiographic Monitoring

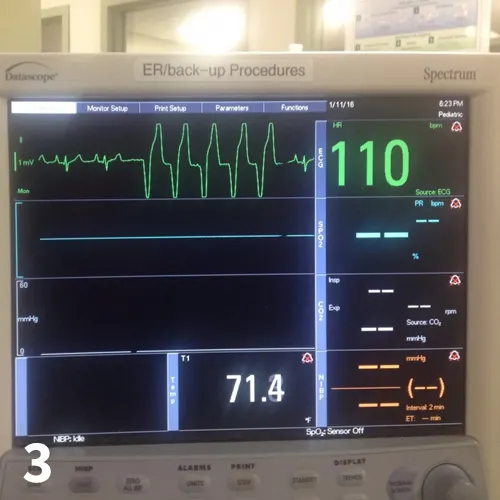

The patient should be connected to an electrocardiograph to monitor heart rate and rhythm during the procedure. The electrocardiogram (ECG) is extremely helpful not only for performing the procedure but also for determining the success of fluid removal by tracking the heart rate.

If the catheter is “tickling” the heart, ventricular premature contractions (VPCs) are likely (Figure 3). If this occurs, the catheter should be pulled out a little to resolve the VPCs. If either paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia or R-on-T phenomenon is present, an assistant can administer a predrawn syringe of 2 mg/kg lidocaine IV. If this does not resolve the VPCs, the catheter may need to be withdrawn and the procedure stopped.

Ventricular arrhythmia on electrocardiography

A prefilled, labeled syringe of lidocaine should be available in case of a ventricular dysrhythmia that requires urgent treatment. If the patient is tachycardic, the heart rate should decrease dramatically as the effusion is drained from the pericardium; by the end of the procedure, the heart rate should be much improved. Persistent tachycardia may indicate ongoing bleeding either within the pericardium or elsewhere. If ultrasonography equipment is not available to evaluate how much fluid remains, the heart rate can be used to find the same information; the heart rate will decrease when the fluid in the pericardium decreases, as the heart can fill appropriately with decreased pericardial pressure.

After the procedure, the patient can be connected to a continuous ECG for ongoing heart rate and rhythm monitoring. If telemetry is not available, hourly evaluation and auscultation of the heart for muffled sounds or tachycardia should be performed. Monitoring should continue for 12 to 24 hours, although timing is variable depending on the individual case.

Step-by-Step: Pericardiocentesis

What You Will Need

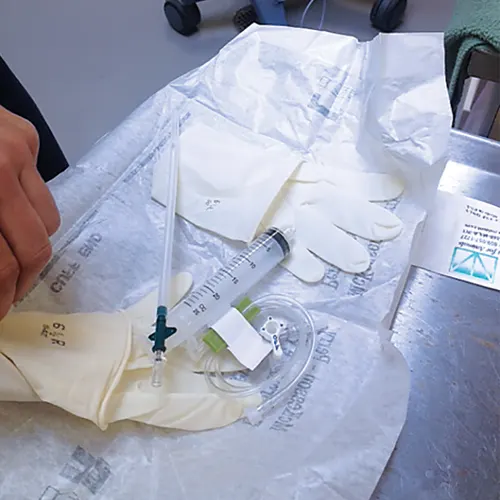

14- or 16-gauge, 5.25-inch over-the-needle catheter (for smaller dogs, an 18-gauge, 2-inch catheter)

Lidocaine for local block (1-2 mL deep SC)

Syringe prefilled with lidocaine for treating ventricular arrhythmias (2 mg/kg IV; maximum 8 mg/kg)

Extension set

3-way stopcock

20- or 30-mL syringe

Collection bucket

Sterile gloves

Surgical scrub

Electrocardiograph to monitor the ECG

Clippers

Sample tubes (EDTA and plain red tops)

An assistant

Performing Pericardiocentesis

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in June 2016 as “Pericardiocentesis.”