This response is correct!

Pancytopenia & Icterus in a Cat

Alex Knetsche, DVM candidate, Kansas State University

Lisa M. Pohlman, DVM, MS, DACVP, Kansas State University

Clinical History & Signalment

Scar, an 11-year-old, spayed domestic shorthair cat, was presented after her owner noted lethargy and vocalization outside the home. Her owners reported she had a poor appetite the previous couple days, and she refused food on the day of presentation. Scar was an indoor/outdoor cat that usually stayed close to home; however, she had reportedly started roaming more than normal after a puppy was introduced to the household ≈7 weeks prior to presentation. No previous health problems were reported. She was free-fed commercial cat food and commercial cat treats several times a week. Flea and tick preventives were up to date.

Physical Examination

Abnormal findings on physical examination included vocalization, dehydration (5%-7%), fever (105.1°F [40.6°C]), icterus, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly.

Diagnosis

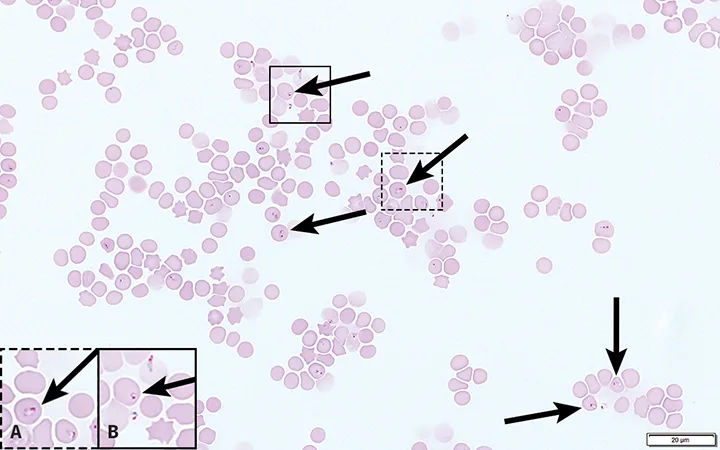

CBC revealed pancytopenia characterized by nonregenerative anemia (hematocrit, 28%; reference interval [RI], 30%-45%), leukopenia (1,900 WBC/µL; RI, 5,500-19,000/µl) due to neutropenia (1,520 neutrophils/µL; RI, 2,500-12,500/µL), and thrombocytopenia (23,000 platelets/µL; RI, 180,000-500,000/µL). Peripheral blood smear examination revealed frequent signet-ring–shaped piroplasms within RBCs (Figure 1).

Serum chemistry profile revealed mild hyperglycemia (184 mg/dL; RI, 70-140 mg/dL) likely due to stress, as well as increased total bilirubin (4.4 mg/dL; RI, <0.2 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (75 U/L; RI, 15-50 U/L), and γ-glutamyl transferase (20 U/L; RI, 0-10 U/L); all of which are consistent with cholestasis. Coagulation testing was not performed in this case.

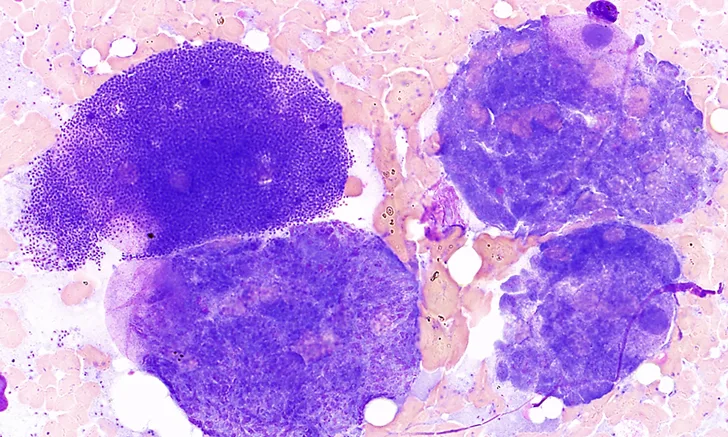

Ultrasound-guided aspirates of the spleen (Figures 2-4) and liver (Figure 5) were collected, and cytologic assessment found abundant schizonts in various stages of maturation.

FIGURE 1

Peripheral blood smear (feathered edge) from Scar; signet-ring–shaped piroplasms (arrows) within RBCs can be seen. Not all organisms are indicated. Modified Wright’s stain, 1000× magnification

DIAGNOSIS:

CYTAUXZOONOSIS

Treatment

Prognosis for cats with acute Cytauxzoon felis infection is guarded, even with supportive treatment and antiprotozoal medication.1,2 A combination of atovaquone suspension (15 mg/kg PO every 8 hours with a fatty meal3) and azithromycin (10 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) for 10 days is considered the most effective therapy for treating cytauxzoonosis in cats.3,4 Supportive care with crystalloid fluids, oxygen therapy, and analgesic medication is key to helping in recovery by improving hydration, increasing organ perfusion and oxygenation, and decreasing high pain levels.1,4 Coagulation testing is recommended, as acute cytauxzoonosis (ie, a form of sepsis) may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). In these cases, some clinicians advocate for heparin therapy (200 units/kg SC every 8 hours) in intensive care settings in which coagulation parameters can be monitored.4 Blood transfusion may be required during the hemolytic stage, which occurs late in the disease.4 To further aid recovery, placement of an esophageal feeding tube is often necessary for adequate nutrition and administration of medications.4 Minimal stress and handling as well as a quiet, dark environment in the cage may be helpful in achieving a positive outcome.

TREATMENT AT A GLANCE

A combination of atovaquone suspension (15 mg/kg PO every 8 hours given with a fatty meal)3 and azithromycin (10 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) for 10 days is considered the most effective therapy for treating cytauxzoanosis.3,4

Supportive care with crystalloid fluids, oxygen, and analgesic medication is key to helping recovery by improving hydration, increasing organ perfusion, and decreasing high pain levels.1,4

Blood transfusion may be necessary.4

In cases in which DIC is present, heparin therapy (200 units/kg SC every 8 hours) may be indicated in intensive care settings where coagulation parameters can be monitored.4

An esophageal feeding tube to administer medications and keep the cat hydrated with adequate nutrition may be indicated.1,4

Minimal stress and handling, as well as a quiet, dark environment in the cage, may be helpful.

Outcome

Due to the high cost of treatment and poor prognosis even with therapy, Scar’s owners elected euthanasia.

Discussion

C felis, a hemoprotozoan parasite, causes cytauxzoonosis in cats. This disease is most common when the tick vector is most active (ie, in spring to early autumn).1 Transmission of C felis occurs via Amblyomma americanum (ie, lone star tick) and Dermacentor variabilis (ie, American dog tick), with A americanum being considered the more competent vector.2 Ticks become infected with C felis when merozoite-infected erythrocytes are ingested from a reservoir species—typically bobcat and domestic cat carriers that survive infection. Replication occurs in both the salivary glands and gut of the tick to form sporozoites,1,5 which are then transmitted to the cat via tick bite. Endothelial monocytes are then infected.1 Transmission of C felis from A americanum can occur as early as 36 hours after attachment by the tick.2 Once sporozoites are present in monocytes, they undergo replication that leads to formation of schizonts.1 In the late stages of disease, schizonts rupture to release merozoites, which infect erythrocytes; these piroplasms are detectable in erythrocytes on a blood smear.1

The most consistent clinical signs of acute cytauxzoonosis are lethargy,4,6 pyrexia,4 and anorexia.4,6 Vocalization,4 lymphadenomegaly,6 icterus,4 and dyspnea4 are also frequently reported. Cats may be hypothermic late in the disease process (ie, just prior to death).4 Clinical signs are typically apparent 10 to 14 days postinfection.5 Pancytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, bilirubinuria, and increase in liver enzymes are common1; however, pancytopenia is not always recognized, and any combination of neutropenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and nonregenerative anemia can be consistent with C felis infection. DIC may also be seen in some cats.4

The mortality rate is high (40%-100%) and depends on whether appropriate, aggressive, and timely treatment was initiated. Even with aggressive treatment, only 60% of acutely infected cats survive.4 Cats that survive infection may be lifelong carriers of the parasite and thereby potential sources of infection for other cats.1

Most pathologic tissue damage that results in clinical signs is due to the schizogenous phase of parasitemia, which causes obstruction of small veins and capillaries of the spleen, lymph nodes, liver, lungs, and other organs, resulting in hypoxic tissue damage and copious release of inflammatory cytokines.4 As a result, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly are typically present.6 Piroplasms can be detected on a blood smear ≈14 days postinfection.1,6 However, because clinical signs usually precede the presence of piroplasms in the blood, visualization of schizonts on cytologic preparations of the liver, spleen, and lymph node can confirm acute disease1 when blood film analysis is equivocal.4 C felis can be fatal in as little as 1 week after clinical signs appear due to thrombosis, tissue infection, and multisystemic inflammation and organ failure caused by schizont dissemination.1,4,5

Due to the poor prognosis and short tick-attachment time required for infection, prevention is ideal; however, in outdoor cats that live in endemic areas, prevention can be difficult even with the use of preventives.2 Acaricides that minimize the time a tick is able to attach to cats, regular manual tick checks and tick removal, and keeping cats indoors in endemic areas (ie, south-central, southeastern, and mid-Atlantic United States), especially during peak tick season, can significantly decrease the likelihood of infection.2,4 Two acaricides—imidacloprid 10%/flumethrin 4.5% collar7 and selamectin/sarolaner topical solution8—have demonstrated efficacy in preventing C felis transmission by A americanum under experimental conditions.7,8

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

Piroplasms within erythrocytes indicate late-stage disease.1,6

Detection of schizonts in cytologic preparations of the lymph node, liver, and spleen can help determine the diagnosis in earlier stages of disease, prior to piroplasmosis.1

Clinical signs of C felis appear 10 to 14 days postinfection, and C felis can be fatal in as little as 1 week after the appearance of clinical signs.1,5

C felis has a high mortality rate; without aggressive treatment, most cats with acute infection die.4

Even with aggressive treatment, only 60% of acutely infected cats survive.4

A americanum and D variabilis are vectors for C felis, so administering a tick preventive and keeping cats indoors can decrease the incidence of C felis in endemic areas.2,4

Two acaricides—imidacloprid 10%/flumethrin 4.5% collar7 and topical selamectin/sarolaner8—have demonstrated efficacy in preventing C felis transmission by A americanum under experimental conditions.7,8