Microchips, Ownership, & Ethics

Bill Folger, DVM, MS, DABVP (Feline), Memorial Cat Hospital, Houston, Texas

Zandra Anderson, JD, Houston, Texas

Microchip placement in companion animals has gained widespread acceptance and is recommended by veterinarians. Microchips help identify lost pets and enable many to be reunited with their owners.

Bill Folger, DVM, MS, DABVP (Feline), Memorial Cat Hospital, Houston, Texas

Microchips, Ownership, & Ethics

However, when a veterinarian finds a microchip in an animal, the discovery presents him or her with ethical, moral, and legal considerations that are difficult to navigate. Adding to the concern is the fact that the prevalence of companion animals currently microchipped is unknown (J Levy, DVM, PhD, DACVIM [SAIM], email communication, May 2016, and C Royal, email communication, May 2016).

The following information can help practitioners navigate the complex and perplexing situations microchipping presents.

Case. No. 1

The following case raises these ethical questions:

Should the veterinarian contact the microchip company to identify the person or organization that implanted the microchip?

Does microchip registration determine ownership of an animal?

What should the veterinarian do if the client demands the microchip registration be ignored?

Mrs. Smith, a long-term client of Dr. Richards at VTB Animal Hospital, calls the practice receptionist to make an appointment for the family dog, Pete, who has received routine care at the practice for many years. The city water meter inspector had accidentally let Pete escape from the backyard, and when he was found roaming the neighborhood later that day, he seemed to be limping. Mrs. Smith wanted Dr. Richards to examine Pete for any injuries.

Dr. Richards finds a right-stifle soft-tissue injury and recommends appropriate medication. Mrs. Smith then asks about microchipping Pete in case he escapes again.

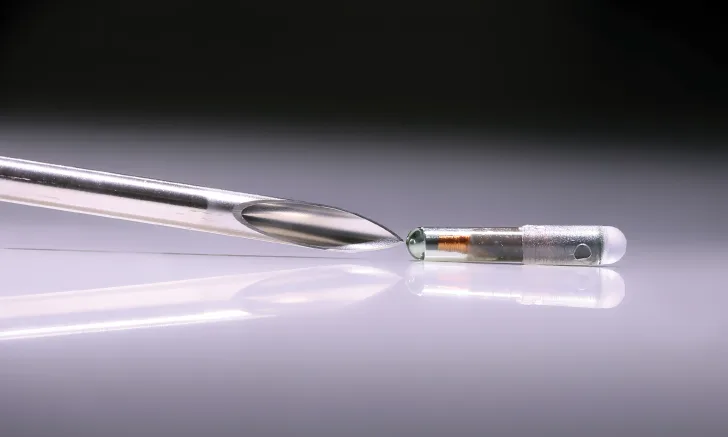

Dr. Richards agrees microchipping is a good idea and asks his veterinary nurse for a standard microchip and a universal microchip scanner. However, when he checks Pete before inserting the microchip, the scanner reveals a microchip between the dog’s shoulder blades.

Dr. Richards tells Mrs. Smith about the microchip. What should he do next?

Contacting the Microchip Company

If the client says he or she does not want the veterinarian to contact the microchip company to identify a previous owner, which is occurring more frequently because microchips are implanted more routinely, that poses many questions for veterinarians and their teams. What are the ethical and regulatory considerations? What are the legal ownership issues? The former are straightforward but cannot be answered without knowing the latter.

Microchip placement in companion animals is now widely recommended by veterinary institutions, animal control agencies, animal shelters, and animal welfare organizations, so more and more veterinarians are faced with this dilemma. Veterinarians always want to do the right thing, but the right thing is not always clear when the client insists no attempt be made to contact the person or agency that placed the microchip.

Defining Ownership

Is the very fact of finding a microchip evidence of ownership? There are conflicting possibilities:

The person or agency that originally microchipped the animal may or may not have been the legal owner. Evidence shows that ownership information is updated in only one-half of microchipped animals,1 meaning the actual owners of the millions of microchipped dogs and cats taken in by animal control agencies, shelters, and humane organizations every year frequently cannot be ascertained.

Microchips identify the pet but not always the owner. For example, a person may know a car’s VIN number, but that does not mean he or she is the legal owner. The car’s actual owner will have a state-issued title for the car with that VIN number. Property ownership requires legally sufficient ownership records as required by the state or local jurisdiction.

No state laws govern transference of microchip ownership. A pet may have been surrendered to an animal shelter or seized by an animal control agency and adopted after the mandatory wait period. A pet may have simply been given to a friend or coworker. In such cases, the pet’s transfer from one owner to another is not legally recognized.

Most importantly, many microchips are never registered, making it impossible to establish any ownership.1 Pets are considered property in every United States jurisdiction, but simply implanting a microchip does nothing to establish ownership.

However, there is good news. Rabies vaccination registrations, collars with identification or rabies vaccination tags, photos and videos, and physical possession of the pet are all indications of ownership, and in some jurisdictions, ownership can be established by licensure. Still, true ownership can rarely be established beyond doubt.

Ownership is a legal concept, not a veterinary professional or ethical concept. Veterinarians are not qualified to establish legal ownership, nor are they qualified to be the pet detective or pet police. (See Microchips & Ownership: Current Laws Provide No Clear Answers)

Confidentiality

The ethical concerns for this case are more easily understood and clearly defined. Dr. Richards, Mrs. Smith, and Pete have enjoyed a long-standing, established veterinarian–client–patient relationship. In most states, the administrative rules governing the practice of veterinary medicine concerning the confidential relationship between the veterinarian and the client is perfectly clear: a veterinarian shall not violate the confidential relationship between the veterinarian and the client. The concept of client confidentiality as an ethical construct is sacrosanct, with only a few exceptions.

Exceptions to the Veterinarian–Client Confidential Relationship

A written or oral waiver of confidentiality by the client of record

Receipt of an appropriate court order or subpoena

The necessity to substantiate collection of a debt

The necessity for disclosure of rabies or a communicable disease2

The AVMA 2015 Principles of Veterinary Medical Ethics3 suggest 2 rules:

Honesty with the client

Respect for the law

In addition, the principles clearly state that the veterinarian shall respect the privacy of the client—and protect that privacy unless required by law. Medical record information must also be considered confidential and cannot be released except in a situation required by law (eg, if a lawsuit were filed and the practice served with a subpoena) or by owner consent.2

Therefore, in this case:

Dr. Richards should not contact the microchip company to identify the person or organization that implanted the microchip.

Microchip registration does not determine ownership of an animal.

Dr. Richards must agree to Mrs. Smith’s request that the microchip registration be ignored.

Dr. Richards would be acting unprofessionally and unethically if he disclosed any information about Pete to a third party. Even disclosing information from Pete’s medical record would expose him to regulatory action, such as violation of client confidentiality, by licensing authorities.

Case No. 2

This case, a recent event at the author’s practice, raises a different ethical question:

Should the veterinarian insist a Good Samaritan allow the practice to identify the registrant of a microchip found in a rescued animal?

On his way home from work, Mr. Jacob notices a young cat that seems to be having trouble moving on the side of the road near his house. Mr. Jacob is a Good Samaritan, so he stops to render assistance and then calls the veterinary practice he is familiar with, which fortunately is just around the corner. He is advised to bring the injured cat to the practice for examination.

\Dr. Anderson determines that the cat has a fractured femoral head and neck. She discusses the injury with Mr. Jacob, who wants to help but is intimidated by the financial estimate.

Dr. Anderson also notices the cat has been neutered, recommends scanning for the presence of a microchip, and finds a standard chip. Mr. Jacob gives Dr. Anderson his consent to identify the microchip, so the veterinarian accesses the AAHA Universal Pet Microchip Lookup and discovers a shelter 5 miles away registered the microchip.

Now, Mr. Jacob can make 1 of 2 decisions:

He can give Dr. Anderson his consent to attempt to identify the current owner through the shelter.

Because of the cat’s injury, he can decide that the current owner is not taking acceptable care of the animal and he does not want Dr. Anderson to contact the shelter. Mr. Jacob is Dr. Anderson’s client, so no one working at the practice is allowed to contact the shelter because that would constitute a violation of confidentiality.

This case also raises a third possibility, which the author experienced at his own practice.

Without informing the attending veterinarian, a practice team member working on the case identifies the microchip number, obtains the name of the microchip company, and contacts the company to determine the microchip registration information. Compounding the dilemma, the microchip company may contact the official designated microchip registrant (who could be a shelter, agency, or owner) directly and communicate the contact information of the practice or agency that made the inquiry. This may in turn lead to the registrant contacting the veterinary practice directly. (When the registrant called the author’s practice, it was explained that the practice could not give out any information about the client because of confidentiality.)

Although no official data is yet available, this situation now occurs frequently, indicating the importance of training the veterinary team explicitly about the ethical and regulatory considerations in these cases.

In this case, Dr. Anderson encourages Mr. Jacob to allow her to contact the shelter because the actual owners, if they can be identified, may want to take care of their pet and assume the financial cost to treat the injury. However, if Mr. Jacob, who is the client in this case, had refused consent, Dr. Anderson would have had to abide by his decision.

Conclusion

No matter the scenario, veterinary professionals are bound by the same ethical and regulatory considerations—no information within the veterinarian–client–patient relationship can be divulged, other than under the few exceptions listed. Until laws are enacted in each state to define what constitutes pet ownership, this will continue to be an uncomfortable collision of regulatory, legal, and ethical considerations.

Potential Court Case

Zandra Anderson, JD, www.TexasDogLawyer.com, Houston, Texas

A Case That Could Have Gone to Court

Heidi, a miniature dachshund that accidentally escaped, was picked up by a Good Samaritan who took her to a veterinarian 19 miles away in another county. The veterinarian scanned the dog and contacted the chip company that in turn contacted the name registered to the chip—a rescue organization.

The veterinarian spoke with the rescue organization’s representative and decided he would not give them the chip number because his client wanted the dog and the dog appeared to be a rescue dog in need of a home. However, the dog did have an owner.

Undaunted by the veterinarian’s refusal to maintain communication, the rescue organization scoured its records for a miniature dachshund placed in the area and discovered 1 of its own volunteers had adopted the dog but failed to register the chip.

The rescue organization contacted the volunteer, who was beside herself trying to find the dog. She contacted the veterinarian, who refused to give her the Good Samaritan’s name. She then contacted the sheriff.

This is where things get interesting.

The sheriff went to the veterinarian’s office to inquire about the dog. The office team refused to give the sheriff any information, stating they would need a subpoena to talk to him, and by all accounts were “snippy.” (Author’s note to all veterinarians: please train your team not to be snippy with a law enforcement officer.)

Back to the Texas law, which is similar to the law in most states. The veterinarian cannot give out a client’s information, even to the sheriff, except by court order. The sheriff was perturbed—he is the sheriff after all. The team had told the sheriff they could not talk to him without a subpoena, so, admonished by the snippy staff, off he went to get a subpoena.

He didn’t get any ordinary subpoena. He served the veterinarian with a grand jury subpoena to testify about a felony theft.

At this point, the sheriff and the veterinarian are mad; the Good Samaritan is mad; the dog owner and her kids are crying (and mad); and the veterinarian’s team is still snippy.

That’s when the dog’s owner hired me. Oh my. Into the hornet’s nest.

Zandra Anderson with Zena and Zeus

I wrote a nice letter to the veterinarian and included touching photos of Heidi with the owner’s 2 children. I respectfully asked if he would pass my letter on to the Good Samaritan and let her know the owner would reimburse her for everything spent on the dog.

When the veterinarian received the letter, he called me right away, but he was still mad. He had to take time off work to testify to the grand jury about the dispute in which he found himself, all because he was upholding his ethical duty to his client. I told him if his client found it in her heart to return Heidi to the owners, I would run interference for him with the district attorney’s office about that pesky subpoena at no charge.

By the way, I had also asked the veterinarian to please make sure the Good Samaritan read that the little boy’s third birthday was coming up and all he wanted was his Heidi back for his birthday present.

Sugar worked better than vinegar, and the dog was returned in time for the little boy’s birthday party. I called the district attorney’s office to let them know the dog had been returned and they agreed the subpoena was no longer necessary. They did ask me to let the veterinarian know they felt his team had been snippy with the sheriff.

The Good Samaritan felt good about reuniting a family, and the rescue organization offered her another dog of her choosing.

This case, however, was settled in spite of, not because of, the microchip, because the dog had an actual owner, and a logical plea with a touch of passion was made on the owner’s behalf. The owner also had veterinary records proving she was responsible, despite her failure to register the microchip.

In this case, the Good Samaritan’s identity could have been obtained via the subpoena, but law enforcement does not usually get involved in ownership disputes and views them as civil matters. If she had refused to return the dog, she could have been identified by suing the veterinarian to get a court order requiring him to name the client in possession of the dog—not a good option for the veterinarian or the owner.

Not all hornet’s nests end so nicely.

Current Laws

Zandra Anderson, JD, www.TexasDogLawyer.com, Houston, Texas

Microchips & Ownership: Current Laws Provide No Clear Answers

Microchips are hailed as the preferred proof of pet ownership to reclaim a pet that has accidentally escaped. However, no state currently mandates microchipping, although local governments may have such laws. Most do not because of a concern about making pet ownership too expensive and difficult for citizens.

On the one hand, some veterinarians, rescue organizations, animal enthusiasts, and, of course, microchip manufacturers promote implanting these devices. One manufacturer urges owners to microchip their pets with the statement “Love isn’t the only thing that will keep them together”1 along with an endearing photo of a little girl and her dog.

On the other hand, others take a dim view of microchip effectiveness in establishing ownership of a lost pet. A VIN News Service attorney contends microchips offer no protection at all and are nothing more than writing a child’s name on a sweatshirt, which does not prove who owns the shirt.2

The reality is somewhere in between. Microchips may be an indication of pet ownership but are not foolproof for numerous reasons:

Someone who finds an unchipped cat does not become the owner by simply microchipping the cat.

A former dog owner may have transferred his ownership rights to another person who failed to register the dog’s chip, but that failure does not mean the new owner relinquished rights to the animal.

An owner can abandon a chipped animal; abandonment is a relinquishment of ownership rights.

Occasionally, a pet’s microchip has migrated to another part of the body and goes undetected. The owner does not lose rights to the pet because scanning failed to produce the chip.

Veterinarians face a real dilemma when a client wants to keep a stray dog or cat but a routine scan finds a registered microchip. In most states, veterinarians face a conundrum. They are bound by ethical considerations and licensing laws. In Texas, a veterinarian may only violate the confidential relationship between veterinarian and client in specific circumstances3 (see Exceptions to the Veterinarian–Client Confidential Relationship, in Ethical Questions), so what can be done?

No Black & White

Quite frankly, current laws do not provide a clear answer, but one of my cases illustrates the dilemma and how it was solved. (See A Case That Could Have Gone to Court, in Potential Court Case) In my case, I was hired by an owner whose dog was found by a Good Samaritan who wanted to keep the dog, which brought up the question of what legally constitutes ownership.

No black-and-white definition of ownership in Texas applies to animals in an ownership dispute. There are, however, several definitions to consider—and they only muddle the picture.

People often think because they have fed a dog or cat for some number of days they automatically own the animal because municipal ordinances all over the country employ language to hold people responsible for strays they feed.

A person who feeds a dog or cat is also responsible for the animal’s rabies vaccination and other veterinary care. Ordinances are written in this fashion so people cannot disavow ownership to get away with not providing veterinary care, or not being responsible for a dog deemed legally dangerous.

Defining Owner

In Houston, for example, the animal ordinances define owner as any person who owns, harbors, or has custody or control of an animal.3 The Texas statute regarding dangerous dogs defines owner as a person who owns or has custody or control of the dog.4 Finally, the Texas Penal Code defines an owner as someone who has title to the property, possession of the property—whether lawful or not—or a greater right to possession of the property than the actor.5

The more documents a person can produce, the more likely he or she will be found the animal’s owner.

These definitions are employed in various connotations for the sole purpose of holding an actor accountable. They do not rely on who has title to the property but rather who has taken some sort of responsibility for the animal by feeding, harboring, or possessing it. The government does not want to wrangle over legal title to the property to impose sanctions for a dog attack, failure to vaccinate an animal, or stolen property. However, when it comes to civil legal ownership of property, the issue of who has title comes into play.

No state statute provides a definition of ownership when people are fighting over who owns a cat or dog. Courts will look to a number of things that may establish ownership:

Veterinary records

Rabies certificate

Bill of sale

Pet registration with a kennel club

Municipal or county registration of a pet

Photographs

Training certificate

Titles on the dog or cat

Adoption contract

Microchip

The more documents a person can produce, the more likely he or she will be found the animal’s legal owner. Many think the microchip is the slam dunk for someone claiming to be the owner, but, in reality, it is only 1 of numerous things that may establish ownership.

Finders & Keepers

The common law of Texas (ie, a judge has made the law from court decisions) provides that if someone finds lost property, the finder has superior rights to the property against all others except the true owner.6 In fact, the law considers the finder of lost property to have established a bailment for the benefit of the true owner (ie, the finder is keeping the property to return to the actual owner).<sup7 sup> The law also provides that a person who has abandoned lost property has relinquished owner rights.8 But, an owner dutifully looking for a lost pet has not abandoned the property. If an owner decides the pet has been hit by a car and quits looking, this could be construed as an abandonment of property rights—an actual case in which the finder won.

To further complicate the issue, in Texas, the power to impound dogs and cats is given to the local rabies authority of cities and counties if they have enacted restraint laws.9 Therefore, according to state law, only local animal control facilities can impound dogs and cats.10 Houston takes it a step further and makes it a misdemeanor for a person who impounds a dog or cat if they do not take it to an animal control facility.11

These laws also commonly occur in other jurisdictions. However, cities do not commonly enforce laws that prohibit citizens from taking in stray animals because that adversely affects their shelter’s live release rate.

What Can Be Done?

Veterinarians can innocently find themselves in a legal bind because an animal has a microchip. Microchips can make a veterinarian vulnerable. The veterinarian’s responsibility is to provide healthcare to his patients, not to become a witness in an ownership debate. However, this is happening more frequently as microchipping becomes more widespread.

Be familiar with the veterinarian–client confidentiality rule and its exceptions.

Be prepared to have a meaningful conversation with the client regarding returning a pet to its owner.

Consider putting language in a consent form for treating stray animals, stating that if a microchip is found, the owner who has registered the chip will be contacted.

Avoid becoming the mediator—this is not the role of the veterinary professional.

Seek legal advice.

Conclusion

Microchipping is, on balance, a good thing that helps establish pet ownership, but it is not a foregone conclusion the chip has revealed the legal owner and the pet will be returned. Further, microchips do not always sway finders to return an animal they have bonded with and want to keep.

The law is an evolution that incorporates changes in values and technology, but is often slow to respond, and has not yet caught up with microchipping technology. Veterinarians and attorneys must be vocal in shaping new laws regarding microchips and in the interim be creative in dealing with ownership disputes.