Megaesophagus

Profile

Definition

Megaesophagus is a condition of esophageal dilation and dysmotility. It may be diffuse or regional/segmental and is further classified as:

Congenital or acquired

Idiopathic or secondary to other esophageal or nonesophageal diseases.

Megaesophagus may be the only manifestation of a systemic disease, such as focal myasthenia gravis.

Systems

Megaesophagus is a disorder of the esophagus but may occur with more generalized disease conditions. The respiratory system may be secondarily affected (aspiration pneumonia, rhinitis) by exposure to regurgitated esophageal contents.

Genetic Implications

Congenital megaesophagus is heritable as a simple autosomal dominant or recessive trait with high penetrance in miniature schnauzers1 and as a simple autosomal recessive trait in fox terriers.2

Incidence/Prevalence

Megaesophagus is the most common cause of regurgitation in dogs and cats; however, it is more common in dogs than cats.

Causes

Causes of megaesophagus are classified as:

Figure 1. Generalized megaesophagus in a 2-month-old dog. The trachea is displaced ventraly, and there is increased soft tissue present overlying the dorsal mediastinum.

Congenital: Onset of signs at weaning (Figure 1)

Inherited

Idiopathic

Secondary

Vascular ring anomaly (Figure 2)

Glycogen storage disease

Myasthenia gravis

Figure 2. Regional megaesophagus secondary to vascular ring anomaly (persisant right aortic arch) in an 8-month-old mixed-breed dog. There is sever distension of the esophagus cranial to the heart base with accumulaton of fluid, a small amount of gas, and ingesta in the esophageal lumen, and ventral displacement.

Acquired: Young adult to middle age (7–15 years)

Idiopathic

Secondary

Autoimmune: Thymoma

Endocrine: Hypoadrenocorticism

Gastrointestinal:

Esophagitis (segmental dilation)

Esophageal obstruction (foreign body, stricture, mass, hiatal hernia, GDV)

Metabolic: Electrolyte disturbances

Neuromuscular:

Botulism

Canine distemper

Dermatomyositis

Dysautonomia

Myasthenia gravis

Neosporosis

Polymyositis

Polyneuropathy

Tetanus

Toxicity

Australian tiger snake venom

Lead

Organophosphates

Pathophysiology

Dysmotility due to dysfunction of esophageal muscle or nerves results in esophageal dilation and accumulation of food and fluid. Idiopathic megaesophagus may be due to selective dysfunction of vagal afferents innervating the esophagus, resulting in an abnormal neural response to distension and failure of peristalsis. Inability to move food into the stomach leads to weight loss and malnutrition.

History & Clinical Signs

Cough and/or dyspnea (secondary aspiration pneumonia)

Hypersalivation

Nasal discharge (secondary rhinitis)

Normal to increased appetite

Regurgitation

Most common sign

Occurs minutes to hours after eating

Liquids often better tolerated than solid foods

Weight loss

Physical Examination

Poor body condition

Mucopurulent nasal discharge with secondary rhinitis

Increased respiratory rate and harsh (increased airway secretions) or diminished lung sounds with aspiration pneumonia (lung consolidation)

Bulge in the cervical region in animals with severe esophageal distension

Patients with secondary megaesophagus may have other abnormalities referable to the associated primary disease.

Pain Severity

Varies from absent (patients without inflammation as a cause or consequence of megaesophagus) to moderate (smooth-surface, inert esophageal foreign body) to severe (esophagitis, caustic or sharp foreign bodies)

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis is confirmed by demonstration of regional or diffuse esophageal dilation on thoracic radiographs or fluoroscopy.

Finding megaesophagus should prompt further investigation to identify potential causes. Endoscopic examination of the esophagus is useful in identifying foreign body, stricture, or esophagitis but is not a good screening test because anesthesia may induce transient loss of esophageal tone.

Idiopathic megaesophagus is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include diseases that disturb esophageal function without causing dilation, and nonesophageal diseases that may cause similar clinical signs.

It is critical to distinguish regurgitation from vomiting, expectoration, and dropping of prehended food, which are not characteristic of esophageal disease.

Laboratory Findings

There are no laboratory abnormalities characteristic of megaesophagus, but abnormalities can reflect underlying primary diseases (eg, hyperkalemia/hyponatremia in hypoadrenocorticism, creatine phosphokinase increases in muscle disease, anemia/basophilic stippling in lead toxicity).

Imaging

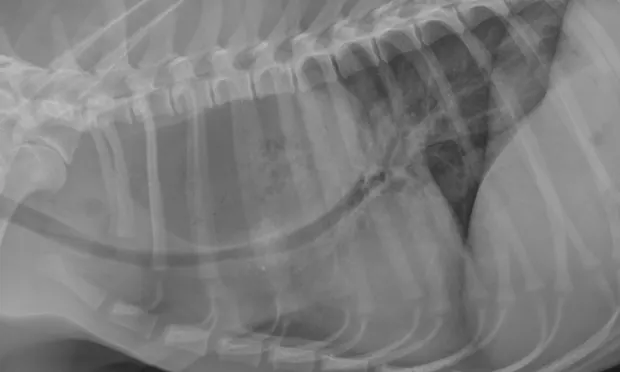

Thoracic radiography demonstrating dilation of the esophagus along a large proportion of its length supports a diagnosis of megaesophagus (Figure 3). See Key Points: Imaging Diagnosis of Megaesophagus.

Megaesophagus may be diagnosed with an esophagram (oral administration of liquid barium followed by radiographic or fluoroscopic imaging). Due to the risk for aspiration pneumonia, contrast studies are often contraindicated unless absolutely needed to establish a diagnosis.

Fluoroscopy offers the advantage of real-time demonstration of motility and is a sensitive and definitive test for megaesophagus, especially in more subtle cases.

Figure 3. Generalized megaesophagus in a 9-year-old pointer. Esophagus is dilated with air along its entire length.

Additional Diagnostic Tests

Additional testing to help differentiate causes of acquired secondary megaesophagus may include:

Acetylcholine (ACh) receptor antibody: Myasthenia gravis (25%–30% of secondary megaesophagus cases)

ACTH stimulation: Hypoadrenocorticism

Atropine response test: Dysautonomia

Blood cholinesterase: Organophosphate toxicity

Esophagoscopy: Esophagitis, foreign body, mass, stricture

Electromyography: Myasthenia gravis, polymyositis

Muscle biopsy: Dermatomyositis, polymyositis, glycogen storage disease

Nerve conduction/nerve biopsy: Polyneuropathy

Skin biopsy: Dermatomyositis

Tensilon test: Myasthenia gravis

Treatment

Medical

Nutritional support

Antibiotics for pneumonia

Oral sucralfate solution for esophagitis

Endoscopic removal or advancement of esophageal foreign body

Treatment of primary disease in patients with secondary megaesophagus

Surgical

Correction of vascular ring anomaly

Esophageal foreign body that cannot be retrieved endoscopically

Resection of strictures that are not resolved with balloon dilatation

Resection of esophageal masses

Activity

Activity should be restricted for at least 30 minutes postprandially.

Nutritional Aspects

High-calorie diet

Multiple, small meals; some patients do best with a gruel and some with canned-food meatballs

Elevated feeding

Elevated feeding with vertical positioning of the esophagus allows gravity to facilitate esophageal emptying into the stomach. Use of elevated bowls is not sufficient.

Elevated position should be maintained for 30 minutes after feeding to optimize this effect. This may be achieved by holding smaller patients upright in the owners’ arms.

Dogs can often be taught to remain positioned with the front feet up on a raised surface or to use a Bailey chair (caninemegaesophagus.org/index.htm), which was developed to maintain proper feeding position.

Placement of gastric feeding tubes may be considered but does not eliminate the risk for aspiration pneumonia.

Medications

Prokinetics

Metoclopramide or cisapride (see Table for dosages)

Action: Stimulate motility of GI smooth muscle; antiemetic (metoclopramide); increase lower esophageal sphincter (LES) tone, which reduces gastroesophageal reflux

Indications: For use in patients that would benefit from increased LES tone (megaesophagus secondary to gastric reflex) or in cats (may stimulate esophageal motility).

Administration: Administer 30 min prior to meals

Ancillary Treatments

Antibiotics (see Table, next page, for dosages) +/- oxygen therapy for aspiration pneumonia

Pneumonia may involve multiple bacterial organisms and caustic injury to lungs

Initial antibiotic choice is empirical; for refractory cases, culture and sensitivity of TTW or BAL samples

Consider combining drugs for broad-spectrum coverage

Gastric acid reducer +/- sucralfate for esophagitis (see Table for dosages)

Fluid therapy if needed

Treatment for primary disease

Precautions

Aspiration pneumonia may be precipitated by performing a barium swallow.

Multiple (sequential) ACh receptor antibody test may be needed to diagnose myasthenia gravis.

Oral drugs may be ineffective if medications are regurgitated or retained in esophagus.

Prokinetics do not stimulate esophageal motility in dogs; they can also increase lower esophageal sphincter tone and prolong esophageal transit time.

Metronidazole can cause neurotoxicity.

Interactions

Metoclopramide: Anticholinergic drugs, phenothiazines, butyrophenones, narcotics, sedatives, tranquilizers

Cisapride: Ventricular arrhythmias when administered with ketoconazole, itraconazole, miconazole

Follow-Up

Patient Monitoring

Clinical status

Body weight

Thoracic radiographs

Prevention

Eliminate congenitally-affected animals from breeding programs

Prevent foreign body ingestion

Relieve obstructions early before irreversible damage occurs

Treat esophagitis aggressively to prevent stricture formation

Prevent esophagitis, when possible (eg, water flush after administration of doxycycline capsules)

Complications

Aspiration pneumonia

Malnutrition

Rhinitis

Course

Congenital megaesophagus may improve or resolve as the patient matures.

Acquired secondary megaesophagus may or may not resolve when the primary disease condition is treated: resolution occurs in about half of myasthenia gravis patients.

Patients with idiopathic megaesophagus show progressive deterioration; adequate nutrition is difficult to maintain in large-breed dogs.

Aspiration pneumonia often recurs leading to death or euthanasia.

Anesthesia- and esophagitis-associated megaesophagus resolves within 2 to 14 days.

Future Follow-Up

Patients with aspiration pneumonia should have thoracic radiographs at 1 to 2 week intervals to guide duration of therapy. Because megaesophagus can be transient, follow-up imaging of newly-diagnosed patients is recommended.

In General

Relative Cost

Initial diagnostic evaluation (physical examination, CBC/serum biochemical profile/urinalysis, thoracic radiographs: $$$

Secondary megaesophagus (additional diagnostics to identify primary disease): $$$–$$$$

Medical treatment and follow-up: $$-$$$$

Surgical treatment of esophageal obstruction: $$$$$

Prognosis

Guarded to poor

Depends on patient age, cause, duration, and presence of complications:

In young animals, esophageal function may improve as they mature; 25% to 50% recover. Secondary megaesophagus may resolve after treating the primary disease.

Patients with long-standing or severe esophageal distension will suffer irreversible esophageal muscle damage.

Prognosis for idiopathic megaesophagus is poor.

Future Considerations

Little reliable published data about megaesophagus are available. Studies to define prognostic indicators should be undertaken to help practitioners make better informed clinical decisions.