Medial Compartment Disease of the Elbow

Profile

Definition

Medial compartment disease of the elbow (ie, the developmental abnormalities affecting the medial aspect of the canine cubital joint leading to osteoarthrosis) encompasses several different conditions that were traditionally grouped as elbow dysplasia.

Conditions that may coexist within the same joint or occur independently include

Medial coronoid disease (MCD)

Fragmented medial coronoid process (FMCP)

Osteochondrosis (OC) of the medial humeral condyle

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the medial humeral condyle

Ununited anconeal process and elbow incongruency have been traditionally grouped under the term elbow dysplasia but are not conditions solely affecting the medial compartment of the elbow and therefore are not included in this discussion.

Related Article: Orthopedic Examination of the Forelimb in the Dog

Systems

The canine cubital joint is a compound, synovial hinge joint composed of the humeral, radial, and ulnar bones and their supporting ligaments and joint capsule.

Genetic Implications

A polygenic disorder with a complex mode of inheritance, which may be affected by numerous environmental factors

Signalment

Species

Dogs are primarily affected.

Breed Predilection

Large- and giant-breed dogs are most commonly affected.

The Labrador retriever, German shepherd dog, and rottweiler are overrepresented.

Age & Range

Clinical signs may develop between 6–18 months of age.

Sex

There is no sex predilection in dogs with OCD.

MCD may occur more frequently in males.

Related Article: Forelimb Lameness & Elbow Pain

Cause & Pathophysiology

OC is caused by a disturbance in endochondral ossification, leading to a region of abnormally thickened cartilage, resulting in ischemic necrosis, flap formation (ie, OCD), and subchondral bone pathology.

MCD may be caused by abnormal load distribution across the elbow joint, caused by various joint incongruities, which lead to pathologic lesions affecting load-bearing joint surfaces. There has been some speculation that MCD is caused by an OC lesion, but this has not been proven.

Several proposed types of incongruity exist, which lead to conflict between the trochlea of the humerus and the medial coronoid process (MCP) of the ulna.

Biomechanical overload results in cartilage damage and/or erosions, subchondral microcracks and/or fissure formation, and fragmentation of the MCP.

A cycle of cartilage damage and degradation ensues, leading to the development and propagation of osteoarthritis (OA) in affected joints.

History & Clinical Signs

The immature patient

Acute or chronic weight-bearing or nonweight-bearing lameness that worsens after exercise and is intermittent or constant in nature

Bilateral disease that may result in a waddling gait and no limping

Exercise intolerance

The mature patient

Chronic, intermittent lameness that may worsen after rest and improve with moderate activity

Stiffness after rest

+/- History of lameness during immaturity

Physical Examination

Varies with age, disease stage, and severity

Limping ranges from imperceptible to severe

Shortened stride

Stiffness

Elbow held in adduction; antebrachium rotated laterally

Pain on elbow extension, flexion, and supination

Pain when direct pressure placed on medial compartment of joint

Decreased range of motion, crepitus, joint effusion, joint capsule thickening, muscle atrophy

Related Article: Forelimb Lameness in a 2-year-old Labrador Retriever

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

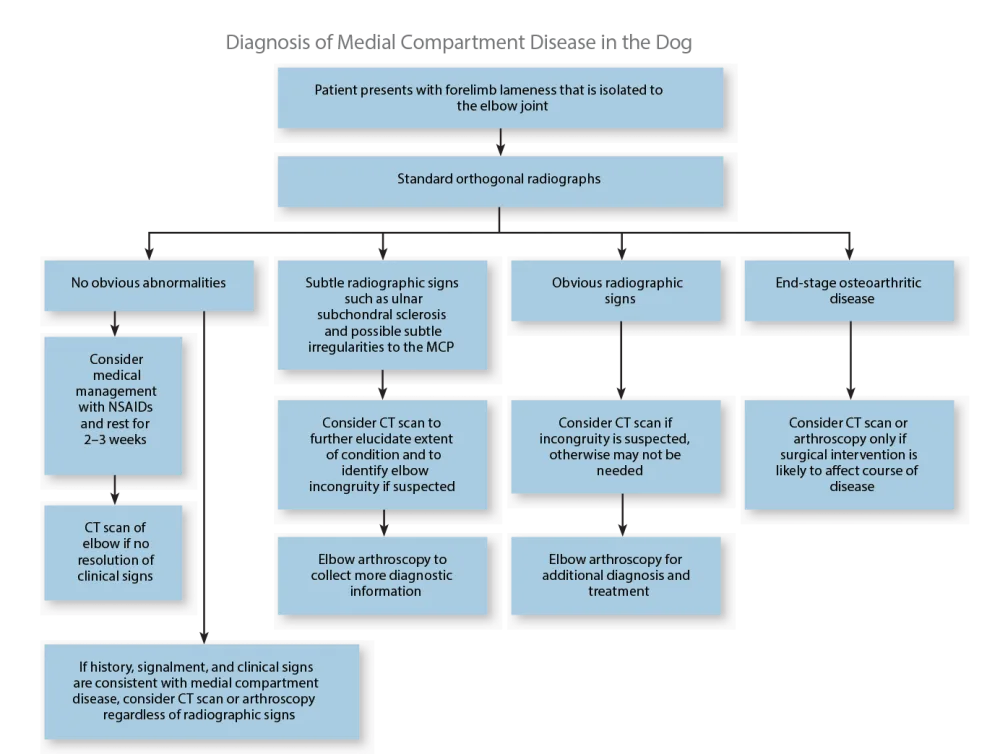

High index of suspicion when any young, large-breed dog presents with elbow pain and lameness (see Diagnosis of Medial Compartment Disease in the Dog).

Orthogonal radiographs may confirm diagnosis, especially with OCD lesions (Figures 1 and 2).

Both limbs should be imaged because of bilateral disease incidence (33%–80%).

Figure 1. Craniocaudal view of an elbow with OCD lesion (arrow).

Figure 2. Mediolateral projection of the elbow: example of humeroradial and radioulnar incongruence and associated MCD. The arrow denotes a step lesion between the coronoid process of the ulna and the radial head. Note the subchondral sclerosis and the ill-defined border of the MCP.

Standard radiographs lack sensitivity for MCD lesions; more advanced diagnostics should be considered in cases with a high index of suspicion but lack of radiographic signs.

Definitive diagnosis is ultimately attained from CT scan and/or arthroscopy.

Differential Diagnosis

Traumatic fractures

Panosteitis

Hypertrophic osteodystrophy

Muscle strain or ligamentous injuries

Immune-mediated or tick-borne polyarthropathies

Standard Imaging*

Standard radiography (see Common Radiographic Lesions Associated with Medial Compartment Disease in the Dog)

Mediolateral (90°), flexed mediolateral (45°), and craniocaudal (20°)

Craniolateral caudomedial oblique projection (for OC visualization)

Distomedial proximolateral oblique projection (for MCP visualization)

CT scan

May help differentiate between MCD vs FMCP to assist in formulating treatment plan

Alternative Imaging

Ultrasonography to image soft tissue joint structures; possible visualization of a FMCP

MRI, if CT not available or if primary cartilaginous lesions (ie, OCD) suspected

Other Diagnostics

Arthroscopy

Gold standard diagnostic modality

May be used with CT to fully characterize lesions

Treatment

Surgery

Arthroscopy

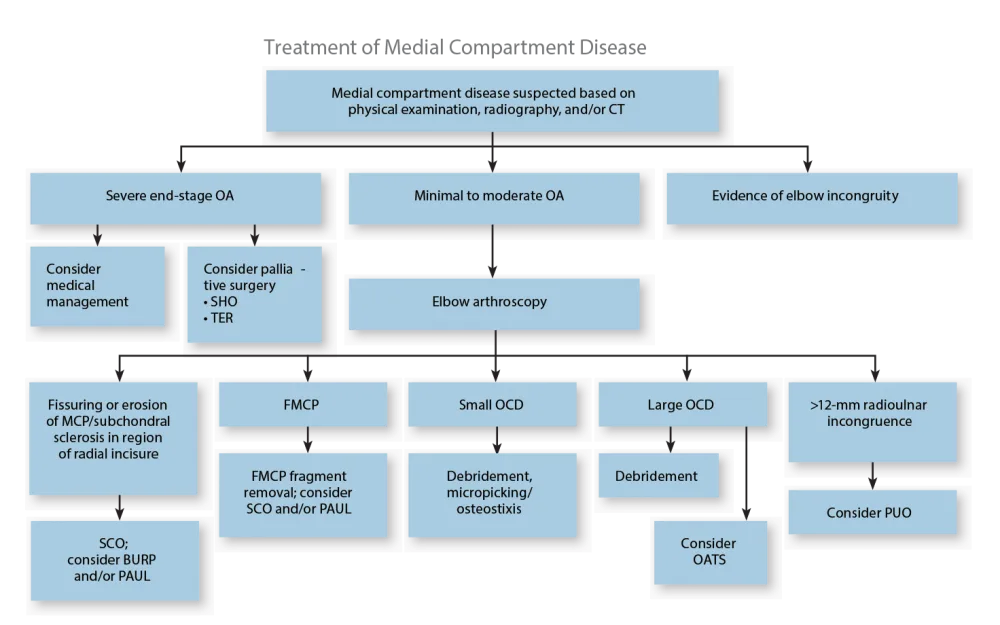

Considered the gold standard of treatment options in the initial management of the disease (see Treatment of Medial Compartment Disease)

FMCP/MCD

Arthroscopic/surgical removal of medial coronoid fragments

Arthroscopic/surgical subtotal coronoid ostectomy (SCO)

Used when fragmentation is not found, but MCD is still suspected based on fissures or erosions and presence of subchondral sclerosis.

Some advocate SCO in all cases, regardless of fragmentation.

Biceps ulnar release procedure (BURP) is used when rotational incongruity is suspected based on lesions found during arthroscopy (lesions along the radial incisures of the MCP).

Proximal ulnar osteotomy (PUO)

Used when radioulnar or humeroulnar incongruity is suspected based on CT or arthroscopy

Proximal abducting ulnar osteotomy (PAUL)

A relatively new technique, serves to unload the medial compartment of the joint.

Considered most useful in young patients, early in course of the disease

OCD

Arthroscopic/surgical curettage, osteostixis or micropicking to address small lesions

Surgical osteochondral autogenous transfer (OATS) procedure to address large OCD defects

Palliative surgery

Used when osteoarthritis is severe or after failed attempts at definitive surgical treatment

Sliding humeral osteotomy (SHO)

Unloads the medial compartment of the elbow joint when the cartilage is damaged or absent

Canine unicompartmental elbow (CUE) replacement

Resurfaces the weight-bearing portion of the medial compartment of the elbow when cartilage is absent

Total elbow replacement (TER)

Medical Therapy

Aimed at alleviating the symptoms of osteoarthritis

Considered in patients where surgery is not an option or adjunct to surgical treatment

NSAIDs

Pain medication (eg, tramadol, gabapentin, amantadine)

Joint health supplements (eg, glucosamine, chondroitin, omega-3 fatty acids)

Exercise modification

Physical rehabilitation

Nutritional Aspects

Weight reduction and calorie restriction to decrease stress on joints

Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation

Client Education

A thorough and costly diagnostic workup and therapeutic plan may be needed.

Arthroscopy has the potential of eliminating clinical signs.

Relief may be temporary and lameness may recur as a result of osteoarthritis.

Early diagnosis and treatment can improve prognosis.

Patients may need chronic medical or surgical treatment as they age.

Alternative Therapy

While unproven, various alternative modalities have been attempted to ease clinical signs of OA

Acupuncture

Laser therapy

Massage

Follow-up

Patient Monitoring

Patients are monitored 8–12 hours postoperatively.

If clinical signs persist, medical therapy should be instituted or continued and other surgical options considered.

Future Follow-up

Dogs should be periodically monitored for advancement of OA.

Medical treatment should be altered based on response to therapy, with modifications in dose and regimen according to clinical signs at home and during physical examinations.

In General

Relative Cost

Most forms of surgery and arthroscopy: $$$$$

Elbow replacement: $$$$$

Medical treatment (over the course of a patient’s lifetime): $$$–$$$$$

Adjunctive physical rehabilitation: $$$$$

Prognosis

Guarded

Depends on severity of OA progression

Prevention

No preventive measures available beyond controlling breeding practices.

Future Considerations

Although decades of research have been dedicated to the components of medial compartment disease, little is known about its pathogenesis. Further research is necessary to help justify the current treatment options and develop new modalities for future patients.

*No one imaging modality is 100% sensitive and specific for diagnosis.

BURP = biceps ulnar release, CUE = canine unicompartmental elbow, OATS = osteochondral autogenous transfer, OC = osteochondrosis, PAUL = proximal abducting ulnar osteotomy, PUO = proximal ulnar osteotomy, SHO = sliding humeral osteotomy, TER = total elbow replacement

FMCP = fragmented medial coronoid process, MCD = medial coronoid disease, MCP = medial coronoid process, OA = osteoarthritis, OC = osteochondrosis, OCD = osteochondritis dissecans, PAUL = proximal abducting ulnar osteotomy, SCO = subtotal coronoid ostectomy

NICOLE S. AMATO, DVM, DACVS, is a small animal soft tissue and orthopedic surgeon at Intown Veterinary Group, MetroWest in Natick, Massachusetts. Her clinical interests include developmental orthopedic diseases, soft tissue reconstructive surgery, cardiothoracic surgery, and minimally invasive laparoscopic and arthroscopic techniques. Her areas of interest are chronic wound healing, delayed unions/nonunions, and multidrug resistant nosocomial infections. Dr. Amato earned her DVM from Tufts University. She then completed a small animal medicine and surgery rotating internship at New England Animal Medical Center in West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, followed by a joint residency in small animal surgery at Tufts and Angell Animal Medical Center.