Locoregional anesthesia techniques can be incorporated in anesthesia protocols to provide high-quality perioperative analgesia and can decrease perioperative use of opioids and anesthetics, reducing the occurrence of anesthetic complications (eg, hypotension, hypoventilation, nausea, vomiting).1-3 Decreasing perioperative use of opioids is also associated with preserving immune system activity and reducing the stress response associated with surgery.4 Locoregional techniques are a key component of enhanced postoperative recovery protocols, enabling faster recovery, shorter hospital stays, and improved patient comfort.5

Many types of locoregional anesthesia techniques are used in veterinary medicine, but this article focuses on the transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block, a fascial plane block that is designed to desensitize the abdominal wall and can provide intra- and postoperative analgesia.2 With fascial plane blocks, a local anesthetic is injected into the space (ie, plane) formed by the connective tissue layer that contains nerves or plexuses between muscle groups, allowing the local anesthetic to spread within the plane and block the target nerves. The abdominal body wall is formed by the external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, rectus abdominis, and transversus abdominis muscles. The fascial plane between the transversus abdominis and internal abdominal oblique muscles forms the TAP, which contains the ventral branch of the last thoracic (T9-T13) and lumbar (L1, L2, L3) spinal nerves. These nerves supply sensation to the abdominal muscles, overlying dermal tissues, and parietal peritoneum.6 Injecting local anesthetic into the TAP can therefore block the nerves that innervate the abdomen, providing local anesthesia and analgesia to the abdominal wall (Figure).

Drawing of a dog in dorsal recumbency showing the anatomic area desensitized by a TAP block (shaded area)

Uses for Transversus Abdominis Plane Block

The TAP block can provide analgesia for abdominal surgeries, including exploratory laparotomies, mastectomies, and ovariohysterectomies. This block provides effective analgesia for the abdominal wall but does not provide reliable visceral analgesia.2 A multimodal analgesic approach titrating opioids, dissociative drugs, or alpha-2–adrenergic agonists in combination with the TAP block is therefore appropriate when visceral pain is expected from surgery. Visceral pain originates from internal organs and is often described in human medicine as deep, dull, or aching discomfort; somatic pain arises from the skin, muscles, or bones and is typically described as sharp and well localized.

Although not indicated to treat visceral pain, the TAP block may provide analgesia in patients with pancreatitis.7,8 The mechanism of action for alleviating pain associated with pancreatitis is unclear; however, desensitization of the parietal peritoneum, which is innervated by the ventral branches of the caudal thoracic and lumbar nerves, may contribute to the analgesic effect.

Considerations for Transversus Abdominis Plane Block

Before attempting to perform a TAP block, adequate training in ultrasound-guided techniques, knowledge of anatomy and sonoanatomy, and an understanding of potential complications are critical. Continuous visualization of the needle during block administration is crucial to ensure the needle does not puncture intra-abdominal organs.2 Complications from locoregional anesthesia (eg, intra-abdominal puncture, damage of abdominal organs, hematoma of the abdominal wall [if a vessel is punctured], local anesthetic systemic toxicosis, infection/abscess caused by improper technique, incomplete block) are rare, but monitoring is needed. To reduce the likelihood of intra-abdominal injection or abdominal organ puncture, the needle should not be advanced if the tip is not under direct ultrasound visualization. To avoid local anesthetic toxicosis, additional local anesthetics (eg, lidocaine CRI) are not recommended.

There are multiple descriptions of how to perform a TAP block. In the authors’ experience, the 4-point technique provides the most inclusive coverage of nerves within the TAP.9

Step-by-Step: Transversus Abdominis Plane Block

What You Will Need

21-gauge, 2- to 3-inch, Quincke (short-bevel) spinal needle

3-, 5-, or 12-mL syringe, depending on the volume to be injected

T-port

Ultrasound machine

Linear array transducer (>12 MHz)

Alcohol or sterile ultrasound gel

Local anesthetic (bupivacaine or ropivacaine 0.2%-0.25%; total volume, 1.2 mL/kg)

Sterile sodium chloride to dilute the local anesthetic (optional)

Dexmedetomidine (0.5-1 µg per mL of bupivacaine solution used) as a coadjuvant for the block (optional)

Step 1: Position the Patient

Anesthetize or heavily sedate the patient and place in dorsal recumbency.

Step 2: Prepare the Abdomen

Shave the patient from xiphoid to pubis, and perform sterile preparation of the abdomen.

Step 3: Draw up the Local Anesthetic

In an adequately sized syringe, draw up the total volume of the local anesthetic (eg, bupivacaine 0.25%, 1.2 mL/kg).

Author Insight

The total volume of the local anesthetic should be equally divided into 4 aliquots (eg, 0.3 mL/kg per injection site). For example, for a 55.1-lb (25-kg) dog, a total of 30 mL of bupivacaine 0.25% is needed, and 7.5 mL should be injected at each injection site. The total dose of bupivacaine or ropivacaine should always be calculated; the authors recommend not exceeding 2 to 2.5 mg/kg of bupivacaine or 2.5 to 3 mg/kg of ropivacaine.

Sterile sodium chloride can be used for dilution of the local anesthetic to a 0.2% to 0.25% concentration and to ensure adequate volume (eg, 1.2 mL/kg) for dispersion within the TAP.

Dexmedetomidine (0.5-1 µg per mL of bupivacaine solution used) can be administered to extend the duration of the sensory block. Postoperative analgesia using bupivacaine 0.25% in conjunction with dexmedetomidine can last up to 12 hours. Liposomal bupivacaine does not appear to extend the duration of the TAP block compared with bupivacaine and dexmedetomidine combined.10

Step 4: Prepare the T-Port & Needle

Attach the T-port connector to the syringe and an appropriately sized spinal needle. Prefill the T-port and needle with the local anesthetic solution to eliminate air.

Author Insight

Using a T-port to connect the needle to the injection syringe can increase ease of handling and drug administration. Echogenic needles may improve ultrasound visualization. An extension line can help improve accuracy by allowing for manipulation of syringe position without moving the needle. This can be particularly useful when the target area is deep or difficult to reach, as it allows for more control and reduces the risk for unintentional movement.

Step 5: Apply Alcohol or Gel

Apply alcohol or sterile ultrasound gel to the cranial abdomen.

Step 6: Visualize the Abdominal Wall via Ultrasound

Position the ultrasound transducer on the cranial abdomen over the midline. Adjust the ultrasound depth and gain to obtain a clear image of the abdominal wall.

Author Insight

The linea alba, falciform ligament, parietal peritoneum, and rectus abdominis muscle should be visible.

Step 7: Position the Transducer for Cranial/Subcostal Block

Slide the transducer caudolaterally, parallel to the ribs. Identify the rectus abdominis muscle, transversus abdominis muscle, and parietal peritoneum.

Step 8: Identify the Target Plane

Identify the target fascial plane (ie, TAP) as a hyperechoic line between the rectus abdominis muscle (RAm) and transversus abdominis muscle (TAm).

PP, parietal peritoneum

Step 9: Place the Needle for Cranial/Subcostal Block

Introduce the spinal needle in-plane, under the ultrasound beam through the rectus abdominis muscle. Direct the needle to the target fascial plane between the transversus abdominis and rectus abdominis muscles.

Author Insight

A pop sensation may be felt when the needle enters the target fascial plane.

Step 10: Confirm Needle Placement

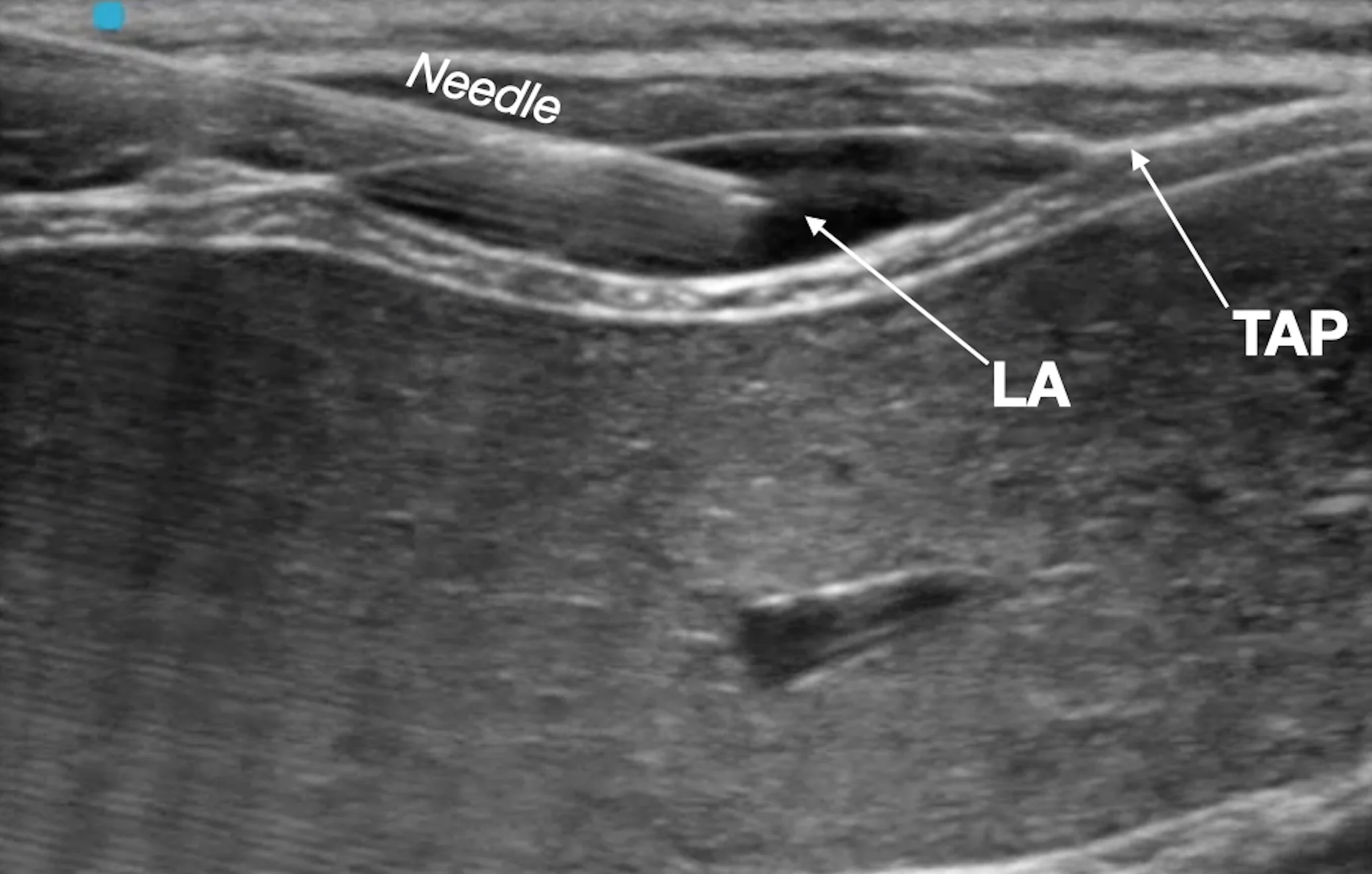

Rule out intravascular needle placement via negative aspiration test, and inject a small aliquot of the local anesthetic (LA) to confirm hydrodissection of the target fascial plane (ie, TAP).

Author Insight

Having an assistant handle the syringe and inject the local anesthetic is recommended.

Step 11: Inject the Local Anesthetic for Cranial/Subcostal Block

Inject one aliquot (0.3 mL/kg) of the total calculated volume of the local anesthetic. Remove the spinal needle following injection.

Author Insight

The injected solution should separate the fascial plane, and anechoic fluid should be seen dissecting the fascia between the muscles. Gentle advancement of the needle into the target fascial plane during injection helps promote wider spread of the local anesthetic.

Step 12: Position the Transducer for Midabdomen Block

Slide the transducer caudally and slightly dorsally, approximately to the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest. Slide the transducer further laterally until the 3 layers of the abdominal wall can be seen in the acoustic window.

Author Insight

The transducer can be oriented transversally or parallel (longitudinal) to the midline. As the transducer is moved laterally, the rectus abdominis muscle disappears from the acoustic window, and only the transversus abdominis and external oblique muscles are visible. The aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle is interposed between the transversus abdominis and external oblique muscles.

Step 13: Identify the Target Plane

Identify the target fascial plane (ie, TAP) as a hyperechoic line between the transversus abdominis muscle (TAm) and internal oblique muscle (IOm).

EOm, external oblique muscle; PP, parietal peritoneum

Step 14: Place the Needle for Midabdomen Block

With the transducer oriented parallel to the midline, introduce the spinal needle in-plane, and direct it to the fascial plane formed between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles.

Step 15: Confirm Needle Placement

Rule out intravascular needle placement via negative aspiration test, and inject a small aliquot of the local anesthetic to confirm hydrodissection of the target fascial plane.

Step 16: Inject Local Anesthetic for Midabdomen Block

Inject one aliquot (0.3 mL/kg) of the total calculated volume of the local anesthetic (LA). Remove the spinal needle following injection.

IOm, internal oblique muscle; EOm, external oblique muscle; TAm, transversus abdominis muscle

Author Insight

Gentle advancement of the needle into the target fascial plane during injection helps promote wider spread of the local anesthetic.

Step 17: Perform Cranial/Subcostal & Midabdomen Blocks on the Contralateral Side

Repeat steps 7 through 16 on the patient’s contralateral side.