Laceration Management in General Practice

Eric R. Pope, DVM, MS, DACVS, Ross University

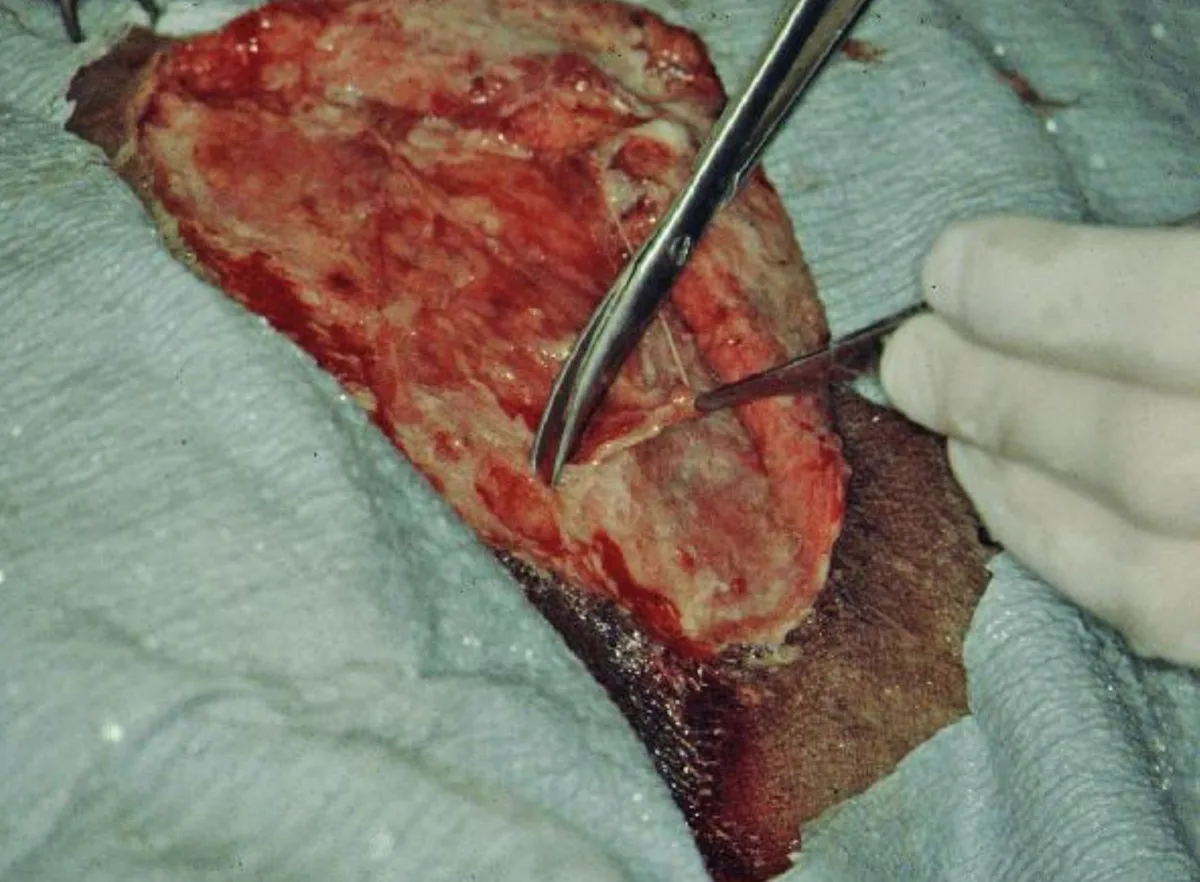

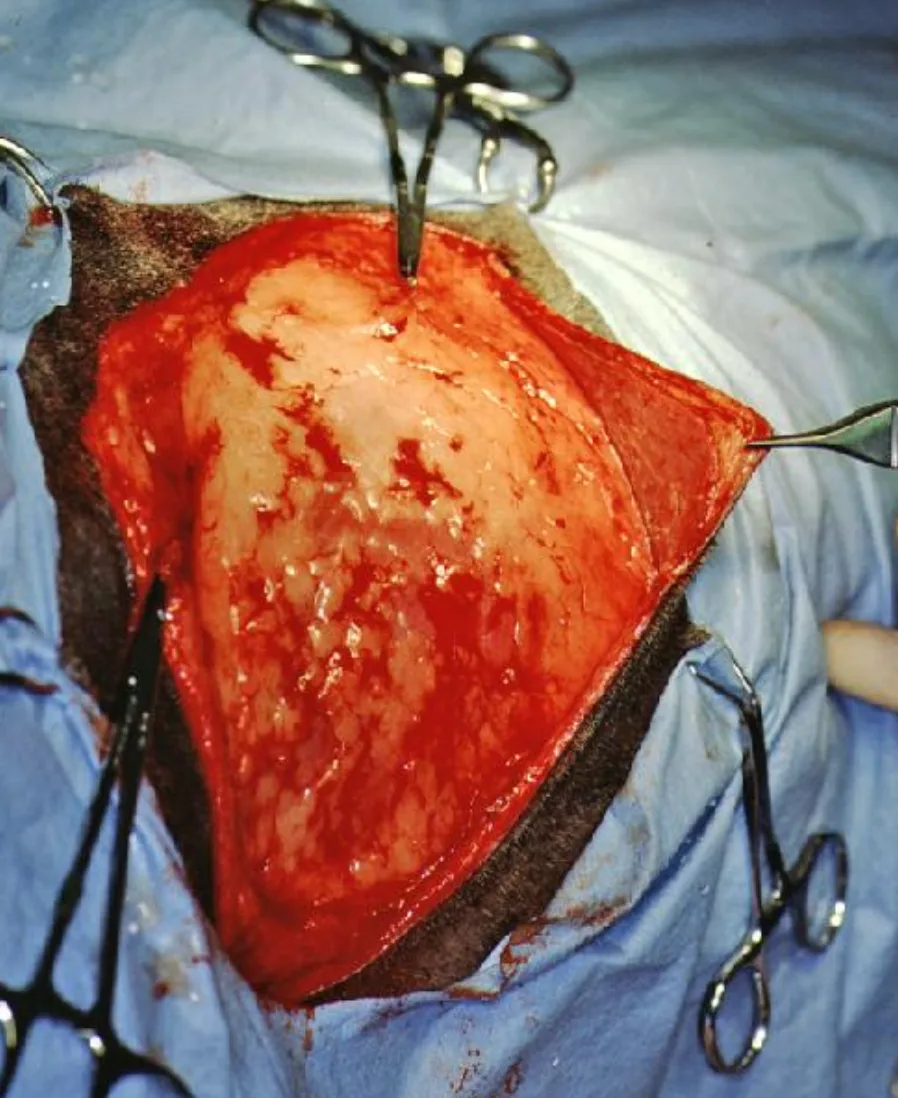

Lacerations from various traumas are common in small animal practice. Severity can vary from superficial lacerations involving only the skin and superficial subcutaneous tissue to significant skin loss with damage to underlying soft and hard tissue (Figure 1). The approach to management is the same regardless of cause or severity.

Superficial laceration involving only the skin and subcutaneous tissue with minimal contamination.

Laceration over the scapula with significant soft-tissue damage and contamination

A complete physical examination and, if necessary, additional diagnostic tests should be performed to identify any internal injuries needing immediate attention.1 Pain sensation should be assessed for significant injuries involving the extremities. If there is a delay in managing the laceration, a bandage can protect the wound from further contamination and improve patient comfort. A minimum database appropriate for the physical examination status and patient age should be performed.

The decision to administer antibiotics should be made at this point and should be based on injury duration and wound condition. Lacerations are initially considered contaminated at best; thus, administration of antibiotics can be justified in most cases. If antibiotics are indicated, a first-generation cephalosporin (eg, cefazolin 10 mg/lb IV), which has a spectrum of activity appropriate for most lacerations, should be administered perioperatively.2 Oral antibiotics (eg, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid at 6.25 mg/lb q12h) should be continued postoperatively if significant contamination or infection is still present after wound debridement and lavage. Local anesthetic blocks, including splash blocks, can be considered, especially if general anesthesia is not administered. The local anesthetic should be administered once the skin around the wound has been clipped and surgically prepped.

After appropriate analgesia, the wound should be explored to determine trauma severity. Wound debridement and lavage are essential for minimizing risk for postoperative complications. Devitalized tissue should be removed via sharp excision and bleeding controlled with digital pressure, application of hemostats, ligatures, or electrocoagulation. Thorough wound lavage (eg, with 0.05% chlorhexidine solution) is effective in flushing loose foreign bodies from the wound and reducing bacterial numbers.3 A syringe and 18-gauge needle are often used, but, if maximum pressure is applied, additional tissue damage may be caused. Recommended pressures of 7 to 8 psi are most consistently achieved when the lavage solution is delivered via a 1-L plastic bag within a cuff pressurized to 300 mm Hg.3,4 The wound can be sutured closed immediately (primary closure) if all foreign bodies and devitalized tissue have been removed and bacterial numbers reduced to a level at which either the body’s defense mechanisms can overcome remaining contamination or it can be eliminated via antibiotic administration. If tissue trauma is more extensive and wound duration is >6 hours, the wound likely should not be closed immediately. If there is any doubt, the wound should be left open for reassessment and repeated lavage before closure.

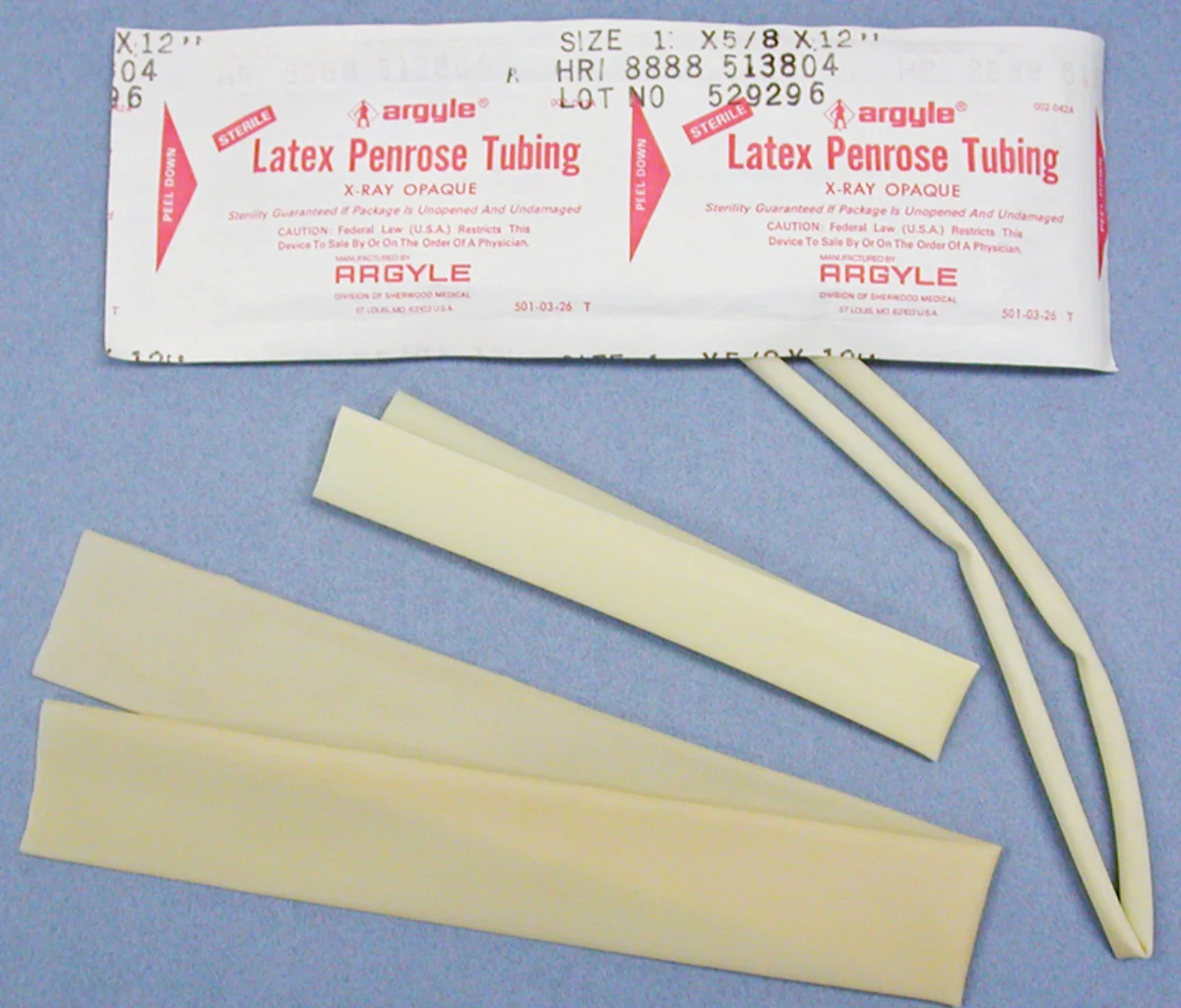

Placement of a surgical drain is indicated when there is concern about residual contamination leading to surgical infection, when the wound is a highly mobile area (eg, flank, axilla), and/or when seroma formation, which may occur when there is excessive dead space, is likely. Many surgeons prefer active drains (ie, closed suction drains), although passive drains (eg, Penrose latex drains) are commonly used in general practice. Both can be effective if used appropriately.

Superficial lacerations involving only the skin and subcutaneous tissue can be closed with skin sutures alone. Buried sutures may be necessary if there are fascial layers that need to be reapposed, if there is excessive dead space, if there will be tension on closure, or to improve cosmesis.5,6 However, placing buried sutures in these wounds increases risk for surgical site infection. Suture material can become colonized by bacteria, which can lead to formation of a biofilm that can interfere with the normal host defense mechanisms and antibiotic effectiveness.7 A recent meta-analysis of surgical site infections in humans8 showed that use of triclosan-impregnated suture material lowered the incidence of surgical site infections in clean, clean-contaminated, and contaminated wounds.8 There is limited evidence regarding effectiveness in veterinary patients, and what has been published does not support their use,2,9 but larger-scale studies are needed to make a final assessment. A short-lasting monofilament absorbable suture material is recommended if buried sutures are used.5 Clinicians should use the minimum number and size of sutures needed to support the tissue.

Postoperative dehiscence of a traumatic wound closure

Accurate apposition of the skin promotes re-establishment of the normal skin barrier that prevents bacteria from gaining access to deeper tissue. Monofilament suture material such as nylon is commonly used. Various suture patterns can be used depending on the length of the laceration and tension on the closure. The author’s preference in most instances is the cruciate (x-mattress) suture pattern, which can help achieve excellent apposition of the skin and absorb mild- to-moderate tension. Staples are a quicker alternative for skin closure. A bandage can be applied to protect the wound closure.

Laceration closure complications include surgical site infection and wound dehiscence (Figure 2). Meticulous wound management, to remove foreign bodies and devitalized tissue, and adequate wound lavage, to reduce bacterial contamination, can reduce the risk for surgical site infection. The incidence of nosocomial infections is minimized by appropriate protection of the wound preoperatively and the use of aseptic technique. A study evaluating humans with traumatic wounds10 showed that the following were associated with an increased risk for infection: increasing patient age, history of diabetes mellitus, jagged wound edges, stellate injury, visible contamination, injury deeper than subcutaneous tissue, and presence of a foreign body.10

Step-by-Step: Laceration Management

What You Will Need

Clipper with #40 blade

Surgical sponges and sterile lubricating jelly

Chlorhexidine scrub (eg, 2%, 4%) and solution

0.05% chlorhexidine solution for wound lavage

20-30–mL syringes

18-20–gauge needle

Sterile drapes and gloves

Laceration pack with needle drivers, Metzenbaum scissors, thumb forceps, hemostats, towel clamps, and scalpel handle with a #10 or #15 blade

3-0 or 4-0 monofilament absorbable suture

3-0 or 4-0 monofilament nonabsorbable suture

Step 1

Pack the wound with sponges (Figure A) or temporarily close it (Figure B) to prevent further contamination and to prevent hair from getting into the wound. If the wound is left open, apply sterile lubricating jelly to the wound surface and use sponges to pack the wound to facilitate removal of any hair or debris that may fall into the wound. Plan the clip for potential drain placement. Perform a surgical scrub of the clipped area, being careful not to get surgical scrub solutions into the wound, and apply the antiseptic solution. Remove sutures or packing material from the wound. Apply sterile drapes around the perimeter of the prepared area. Although not always used, drapes can make it less likely for suture material to become contaminated when contacting skin. Because ample skin was available for wound closure in the pictured case, the traumatized skin at the edge of the wound was excised, leaving healthy skin for wound closure (Figure C).

FIGURE A

Author Insight

Unless the extent of the wound is clearly evident, clip widely in case greater access is needed to thoroughly explore and treat the wound.

Step 2

Perform a thorough examination of the wound, followed by surgical debridement (Figure A) and wound lavage (Figure B). Sharply excise foreign materials and devitalized or severely damaged tissue. Attach a fluid bag and administration set to the syringe and needle with a 3-way stopcock to facilitate efficient delivery of ample amounts of lavage solution to the wound (Figure C). As an alternative, deliver the lavage solution (eg, 0.05% chlorexidine solution) through an administration set and needle attached to a pressurized 1-L bag of fluids.

FIGURE A

Author Insight

The goals of wound debridement and lavage are to remove devitalized tissue and gross debris and to reduce bacterial contamination. If there are concerns about the wound condition, manage it as an open wound until it appears healthy enough for wound closure.

Step 3

If there is concern for postoperative seroma formation or infection, either a passive drain (eg, Penrose drain; Figure A) or active drain (Figure B) can be used. The drain should not lie directly under the suture line, as this may facilitate wound dehiscence.

FIGURE A

Author Insight

Although drains are effective in removing or preventing fluid accumulation, they are foreign bodies and increase the risk for surgical site infection.11

Step 4

If needed, place subcutaneous sutures to help obliterate dead space and/or decrease the tension of the primary skin closure (Figures A and B). A short-lasting monofilament absorbable suture material (eg, poliglecaprone 25, glycomer 631) is recommended. Placing buried sutures allows skin sutures to be apposed under less tension while still achieving good cosmetic outcome.

FIGURE A

Author Insight

If the wound has been properly debrided and lavaged, the benefits of correctly coapting tissue with subcutaneous sutures should outweigh the risk for infection from suture placement.

Step 5

Suture the skin, making sure to correctly appose the skin edges. Edge apposition promotes more rapid wound sealing. The pattern used is surgeon preference based on length of the closure and presence of tension. Interrupted patterns allow the surgeon to remove a few sutures to establish drainage if wound healing problems occur. The author prefers cruciate sutures (Figure A) in most instances, especially when tension is present. The Ford interlocking pattern (Figure B) is a good alternative for longer lacerations if no tension is present.

FIGURE A

Author Insight

With accurate apposition of the skin edges, a fibrin seal will form within hours, decreasing the risk for surgical site infection.

Conclusion

Careful evaluation of the wound, including assessment of the severity of tissue trauma and degree of contamination, helps guide appropriate management. Early intervention via wound debridement and lavage and accurate wound closure can help minimize the risk for postoperative complications.