Key Points in Complicated Canine Corneal Ulcers

Diane Van Horn Hendrix, DVM, DACVO, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Georgina M. Newbold, DVM, DACVO, The Ohio State University

Complicated corneal ulcers are epithelial defects that remain unresolved after several days, become infected, or show progressive deepening into the stroma. Complete ocular examination—including a Schirmer’s tear test and a light examination of the eyelids and conjunctiva—may or may not reveal the underlying cause. Recognizing a complicated ulcer is critical for appropriate management of these potentially vision-threatening keratopathies.

1. Clinical Findings

An ulcer is considered complicated based in part on its depth and duration. Even without a detailed history, the cornea offers clues during the course of the disease. Corneal vessels generally appear at the limbus after 7-10 days, then grow approximately 1 mm per day, so corneal vascularization is a sign of chronicity.

Noninfected ulcers

Epithelial margins of a simple ulcer should adhere tightly to the stroma. The ulcer can range in size from a pinpoint lesion to the entire cornea, and may affect the epithelial layer only, or extend deeper into the stroma.

Infected ulcers

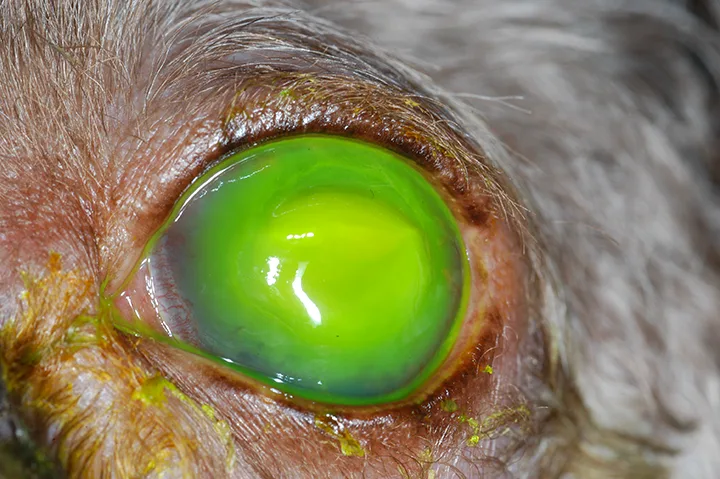

Infected ulcers will typically display a creamy corneal infiltrate around the margins. A gelatinous texture is a sign of corneal malacia (melting), which is commonly seen in ulcers infected with bacteria (Figure 1).

Corneal malacia or melting ulcer. These ulcers need to be managed aggressively to prevent corneal perforation. Images courtesy University of Tennessee, Knoxville, College of Veterinary Medicine

Infected ulcers also can deepen rapidly, resulting in corneal perforation. Infected ulcers occur more commonly in brachycephalic breeds and dogs that are being treated with systemic or ophthalmic corticosteroids.1

Indolent ulcers or superficial chronic corneal epithelial defects

These chronic and superficial ulcers are identified by a nonadherent lip of corneal epithelium surrounding a shallow ulcer. Superficial chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs) persist because of an inherent healing deficit that prevents the epithelium from adhereing to the stroma.

2. Etiologies

An ulcer generally becomes complicated because of infection, indolence (ie, failure of the epithelium to adhere to the underlying stroma), or lack of treatment for the primary cause.

Noninfected ulcers with underlying cause

The cause of many chronic ulcers can be identified during the initial examination. The causes of persistent corneal ulcers include underlying keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) or dry eye, systemic and topical corticosteroid use, and eyelid abnormalities (eg, entropion, defects, ectopic cilia).

Superficial chronic corneal epithelial defect: These indolent ulcers will not heal without intervention.

Infected ulcers

In dogs, bacterial infections are more common than fungal or herpes viral infections, with Pseudomonas and β hemolytic Streptococcus among the common secondary invaders in dogs. Infection is believed to set in after trauma or after another underlying cause creates the initial ulcer. It is important to identify infection, because these ulcers progress more rapidly than noninfected ulcers.

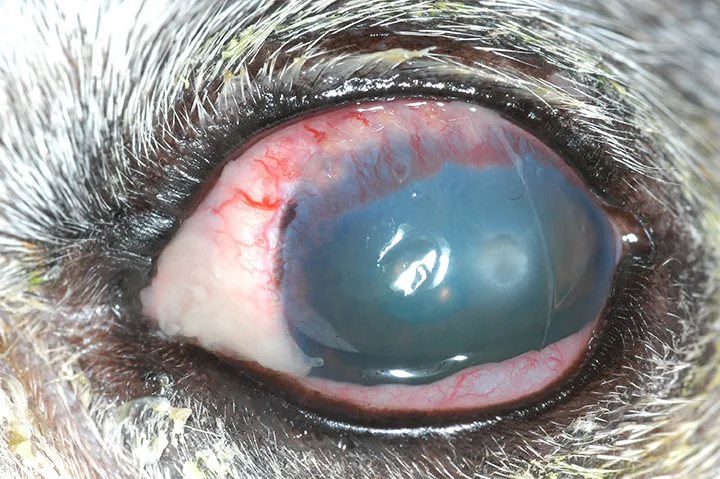

Indolent ulcers

Indolent ulcers—known as SCCEDs or “boxer” ulcers—are those in which the epithelium fails to adhere to the underlying stroma. They are superficial, with minimal stromal edema and no cellular infiltrate (Figure 2).2

3. Diagnostic Testing

Noninfected ulcers with underlying cause

Fluorescein stain becomes apparent on the walls and floor (stroma) of the corneal defect and therefore can be used to outline the defect’s size and depth. Because Descemet’s membrane does not pick up stain, a clear area at the greatest depth of the ulcer indicates the presence of a descemetocele. This is a surgical emergency, because the eye is extremely fragile (Figure 3). A thorough eye examination should be performed to discern a primary cause (eg, foreign material, aberrant hairs, lid defects or dysfunction, dry eye). A Schirmer’s tear test can be obtained to rule out KCS.

Descemetocele with clear area at greatest depth: This cornea is very unstable and at high risk for perforation.

Infected ulcers

When any sign of a cellular infiltrate or evidence of malacia is present, a corneal cytology, culture, and sensitivity should be performed to evaluate for bacterial or fungal organisms (Figure 4). Cytology can be performed in-house; after applying topical anesthetic, the ulcerated surface should be gently scraped with the blunt end of a scalpel blade, brushed with a cytobrush, or a cotton-tipped applicator rolled gently across the corneal defect. The cells should then be gently transferred to a slide. A brief scan under the microscope should reveal corneal epithelial cells; however, the presence of neutrophils, bacteria, or fungal hyphae should prompt a culture. An aerobic bacterial culture will usually suffice, whereas an anaerobic culture is generally not necessary. A fungal culture is required only if fungal hyphae are seen on cytology or other signs of fungal infection (eg, a brown tinge to the ulcer) are present.

Infected superficial stromal ulcer with a cellular infiltrate: A cytology and culture with sensitivity are important in helping to choose appropriate therapy.

Indolent ulcers

These ulcers are typically noted by a loose lip of epithelium that is not always easily visualized but can be revealed by touching the edge with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator after applying anesthetic.

4. Medical Therapy

Topical antibiotics should be used initially with any corneal ulcer to prevent secondary infection. Atropine can be used to decrease pain from ciliary spasm and to dilate the pupil to help prevent adhesion of the iris to the lens.

Noninfected ulcers with underlying cause

Once the underlying cause has been alleviated, these ulcers can typically be managed with a broad-spectrum antibiotic (eg, neomycin-polymyxin B-bacitracin) 4-6 times a day until the ulcer has re-epithelialized. If KCS is the underlying cause, institute cyclosporine 0.2% or tacrolimus 0.03% twice a day in conjunction with the antibiotic to increase lacrimation, along with an artificial tear ointment 4-6 times a day to provide lubrication.3 Atropine may be applied once or twice a day for 2-3 days as needed for pupil dilation and pain relief.

Infected ulcers

Antibiotic application frequency should be aggressive (ie, every 2 hours for at least 24-48 hours). Antibiotics (eg, cefazolin and tobramycin or fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin) should be applied every 2 hours for at least 24-48 hours, with a recheck examination every 1-2 days. Topical application of serum every 2 hours reduces collagenase and protease enzyme activity, and slows the rate of corneal malacia. Atropine is essential to decrease pain from ciliary spasm and to help prevent posterior synechiae (ie, adhesions of the iris to the lens) by dilating the pupil, both of which result from reflex uveitis. Atropine must be applied more frequently (once or twice a day initially). Corneal perforation requires systemic antibiotics, surgery, and topical therapy.

Indolent ulcers or SCCEDs

Gentle debridement with sterile cotton-tipped applicators should be performed on the loose epithelium of indolent ulcers. Oxytetracycline 1% ophthalmic ointment applied 4 times a day may increase the healing rate.4 Atropine may be applied once or twice a day for a few days as needed to maintain pupil dilation.

5. Surgical Therapy

Noninfected ulcers with underlying cause

An ulcer that appears to have been caused by conformational entropion may require a modified Hotz Celsus to place the lid in a normal position. Cryotherapy and hair removal may be needed to address ectopic cilia, distichia, or trichiasis.

Infected ulcers

If an ulcer has become a descemetocele, or reached more than 50% of stromal depth, surgery can be performed to prevent corneal rupture. A conjunctival graft, with or without a collagen graft, can be sutured to the cornea to provide support and a blood supply to enhance healing. Similar techniques are used to treat corneal perforations. These techniques require special instrumentation and magnification and surgical expertise, and referral to an ophthalmologist for surgical management is strongly recommended for deep ulcers or perforated corneas (Figure 5).

Corneal perforation that will require a conjunctival and/or collagen graft to stabilize the globe.

Indolent ulcers or SCCEDs

Indolent ulcers often need more than debridement with a cotton-tipped applicator to heal. Grid keratotomy or diamond burr debridement can be performed to stimulate the epithelium to adhere to the stroma.

Conclusion

Complicated corneal ulcers can be frustrating, and risk of permanent vision loss is high in some circumstances. Consultation with or referral to an ophthalmologist may be the best option to help the dog maintain vision.