Intussusception Reduction

Mikaela Thomason, DVM, Carolina Veterinary Specialists, Huntersville, North Carolina

Christian Latimer, DVM, CCRP, DACVS-SA, BluePearl Pet Hospital, Spring, Texas

Overview

Intussusception refers to invagination of a portion of the GI tract into the lumen of an adjacent segment. It is sometimes overlooked as a potential cause of GI clinical signs in presenting patients. The 2 components of intussusception include the invaginated section (ie, the intussusceptum) and the adjoining segment that holds the intussusceptum (ie, the intussuscipiens).1 Underlying disease processes can alter gut motility, resulting in intussusception.2 Many cases of intussusception are idiopathic and intermittent; thus, diagnosis and treatment of the underlying cause are difficult. Causes of intussusception may include neoplasia, intestinal parasites, viral enteritis, foreign body obstruction, or cecal inversion2,3; previous abdominal surgery is a risk factor.

Intussusception can occur at any age but is most commonly recognized in patients younger than 1 year1 and therefore should be included among the differential diagnoses for any juvenile patient presented with GI signs. Intussusception most commonly occurs at the ileocecocolic junction but can occur along any portion of the GI tract, including the stomach and esophagus.1 Clinical signs at the time of presentation are typically related to the location of intussusception.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic steps include a complete physical examination, abdominal radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography (or a contrast study if ultrasonography equipment is not available). On physical examination, a thickened tubular structure may be palpated in the abdomen, which may be painful for the patient. Abdominal radiographs commonly reveal a fluid- or gas-filled bowel consistent with a mechanical obstruction.2 Abdominal ultrasonography is often the most helpful preoperative diagnostic tool (Figure 1); the finding of multiple hyperechoic and hypoechoic concentric rings in transverse sections, parallel lines in longitudinal sections, or both is diagnostic of intestinal intussusception.4 Abdominal radiography with contrast media (ie, barium) can outline the intussusceptum in the lumen of the intussuscipiens, or the contrast can appear as a ribbon-like structure in the intussusceptum.2

Abdominal ultrasound images of a dog with jejuno-jejunal intussusception secondary to an intestinal sarcoma (A), a dog with ileocolic intussusception (B), and a dog with jejuno-jejunal intussusception without an identifiable underlying cause (C)

Treatment

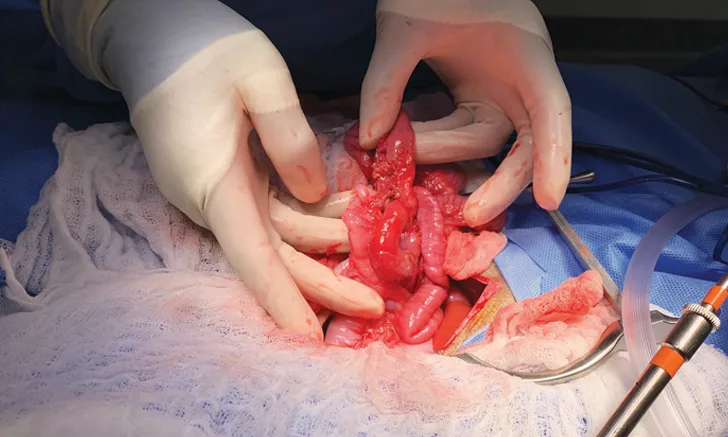

Treatment of intestinal intussusception involves laparotomy with manual reduction if the affected segment appears potentially viable and/or resection and anastomosis of the affected intestinal segment if neoplasia is the underlying cause or if the affected segment is necrotic or cannot be reduced (Figures 2-4).

FIGURE 2

A portion of intestine after intussusception reduction. There is serosal tearing (short arrow) and significant erythema (long arrow).

Enteroplication

Intussusception recurrence rates are ≈6% to 27%, and recurrence is usually observed 3 days to 3 weeks postsurgery.1 Recurrence typically affects the segment immediately proximal to the previous intussusception site.2 Enteroplication reduces the risk for intussusception recurrence by creating permanent adhesions between adjacent loops of intestine. Enteroplication is completed by preparing the intestines using manual reduction or resection and anastomosis of compromised bowel. After the intestines have been prepared, adjoining segments should be placed side by side in a zigzag pattern with care not to create kinks or sharp bends. The adjacent loops should be sutured together with either absorbable or nonabsorbable suture and should penetrate the submucosal layer midway between the mesenteric and antimesenteric borders to ensure a secure hold. Complete plication encompasses plication of the jejunum to the ileum; the duodenum should not be included because it is rarely involved with intussusception.3

Enteroplication can be performed immediately after reduction if the affected segment appears viable and without obvious pathology; however, enteroplication should only be performed in select cases (eg, spontaneous reduction intussusception in young dogs, presence of hyperperistalsis during surgery, cases involving multiple or recurrent intussusception)3 because of the risk for complications. The procedure has been associated with abdominal discomfort, vomiting/diarrhea, hyporexia, constipation, increased risk for future obstructions, bowel strangulation, and intra-abdominal abscess formation.3

Stomach Intussusception

Intussusception involving the stomach is rare and requires a different treatment approach. For example, patients with gastroesophageal intussusception should be treated with left (± right) incisional gastropexy and may require sutures to reduce the size of the esophageal hiatus.5 A partial gastrectomy or Y-U pyloroplasty (ie, a procedure in which the pyloric antrum is advanced aborally) should be considered after reduction of gastroduodenal intussusception.6

Prognosis

For most idiopathic cases of intussusception, the long-term prognosis is good with appropriate aftercare and treatment, but prognosis ultimately depends on the specific underlying cause. In cases for which a diagnosis is not grossly apparent, samples of the area of intussusception, as well as samples of other areas of intestine, can be submitted for biopsy.7 Because intestinal parasitism is also a potential predisposing factor for intussusception, fecal samples can also be collected preoperatively for testing and empiric deworming can be performed in case of false negatives.2

Step-by-Step: Intussusception Reduction

What You Will Need

Basic surgery pack

Hemostats

DeBakey forceps

Scalpel handle

Needle drivers

Suture scissors

Metzenbaum scissors

Mayo scissors

Poole suction

Radiopaque gauze and laparotomy sponges

Balfour retractor

3-0 or 4-0 absorbable monofilament suture

#11 or #15 scalpel blades

Additional instruments that may be helpful:

Doyen forceps

Vessel sealant device

Electrocautery

GI anastomosis stapler

Thoracoabdominal stapler

Step 1

Clip, clean, and perform sterile preparation of the abdomen.

Step 2

Using a standard ventral midline approach, begin abdominal exploratory surgery. Line the abdominal incision with 2 dampened laparotomy sponges along the linea alba. Place a Balfour retractor to allow appropriate visualization into the abdomen.

Step 3

Examine the entire GI tract for abnormalities; multiple occurrences of intussusception may be present.

Step 4

Isolate the area of intussusception and pack off the region with dampened laparotomy sponges.

Step 5

Attempt manual reduction via gentle manipulation. If the intussusception is easily reduced and the affected segment appears viable, complete the exploratory surgery and close the incision in a standard fashion.

If the intussusception does not easily reduce or is associated with an intestinal mass, or if the affected segment is nonviable, perform resection and anastomosis (see Steps 6-10).

A portion of intestine after attempted jejuno-jejunal intussusception reduction. The intussusception could not be fully reduced.

Author Insight

If the intussusception is recurrent, hyperperistalsis is present, or no underlying primary cause is found, consider enteroplication to prevent recurrence. Of note, however, enteroplication can lead to significant postoperative complications.

Step 6

Gently milk intestinal contents away from the portion of intestine that will be resected. Use digital compression or Doyen forceps to gently seal the oral and aboral portions to reduce contamination. Occlude the lumen orad and aborad to the site of resection with gloved and sterile fingers.

Step 7

Isolate the blood supply of the affected bowel segment and ligate appropriately.

Step 8

Sharply excise the affected intestinal tract and discard or place aside for histopathology. Be careful to avoid contamination of the surgical field.

Step 9

Perform either end-to-end anastomosis with absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures or side-to-side anastomosis with surgical and thoracoabdominal staplers.

Step 10

Achieve adequate intestinal closure, then lavage the peritoneal cavity with sterile saline, suture the omentum to the anastomosis site, and close the incision in a standard fashion.

Reduction can often be difficult and may result in significant damage to the affected intestinal segment. View videos of failed intussusception reduction in a puppy and partially reduced intussusception in a 3-month-old Australian cattle dog with chronic intussusception that was later found to be necrotic.