Innovative Intubations: Dealing with Difficult Airways

Jessica Birdwell, BA, LVT, VTS (Anesthesia & Analgesia), University of Tennessee Veterinary Medical Center

Endotracheal intubation can be relatively straightforward, as long as critical landmarks (ie, epiglottis, soft palate, arytenoids, laryngeal aperture) can be identified. However, sometimes these structures are altered or no longer visible (Figure 1), and alternative intubation techniques may be required.

Unknown soft tissue mass growing in a dog’s upper airway obscuring the landmarks typically used for intubation

Following are several options that facilitate intubation and oxygen delivery.

Repositioning

Simply moving a patient from sternal to dorsal or lateral recumbence may cause redundant or obstructive tissue to shift, which allows better visualization of anatomical landmarks.1-3 This is especially beneficial in patients with elongated soft palates, polyps, or masses. (Figures 2A and 2B.)

Elongated palate of an English bulldog, positioned in sternal (A) and dorsal (B) recumbence

Guided Intubations

A stylet or guide tube helps facilitate intubation when the airway is visible but narrowed.

Stylets are metal wires manufactured with a plastic or painted coating and are used to increase the rigidity of an endotracheal tube (ETT), which is particularly helpful with armored (ie, reinforced to prevent kinking and provide flexibility during patient positioning) ETTs. Stylets can also be used to shape an ETT to fit into a curved airway (eg, in swine, primates). With a stylet in place, the ETT’s tip becomes a wedge that is pushed between arytenoids to separate them and allow tube passage. Because the metal is stiff, a stylet increases the risk of tracheal trauma, including rupture, so the tip must remain within the ETT during tube placement.1 Stylets should be discarded when damaged because they can serve as a source of airway debris if the paint or plastic covering is chipped, peeling, or flaking.4

Guide tubes are used to steer the tip of the ETT into the airway. They can also be attached to oxygen to provide supplementation during difficult intubations. They are softer and more pliable than stylets and are often manufactured for other purposes (eg, polypropylene or red rubber urinary tubes, stomach tubes, large bore intravenous catheters5). Like a stylet, a guide tube can be inserted into an ETT, but the tip must protrude slightly. The tip is inserted into the laryngeal aperture and the ETT is then made to slide over the guide tube and into the airway.

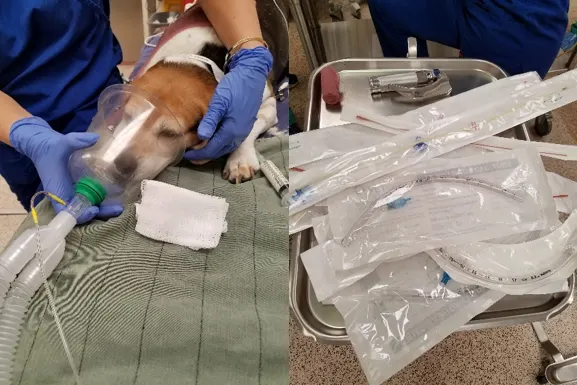

Alternatively, the patient can first be intubated with the guide tube (Figure 3). The ETT is then placed over the external end of the guide tube and made to slide down the tube into the airway, and the guide tube is removed. For this technique, the entire guide tube must be narrower than the ETT and about 2.5 times its length. This technique is also effective in exchanging endotracheal tubes intraoperatively when there is minimal visualization or an inability to reposition the patient.

Figure 3A

Provide supplemental oxygen until the patient is prepared.

Endoscopic Guidance

Endoscopic guidance is beneficial when the laryngeal aperture cannot be visualized because of abnormalities in oropharyngeal, laryngeal, or nasopharyngeal anatomy; in species in which the mouth cannot be opened widely; or when the patient is too small for normal techniques. An endoscope can be placed through an ETT (Figures 4 and 5), alongside an ETT, or through a nasal passage to allow visualization of the ETT tip as it enters the laryngeal aperture. Besides permitting evaluation of anatomical structures and confirmation of tracheal intubation, endoscopic intubation is essential in patients undergoing selective one-lung ventilation or bronchial blocking (eg, for thoracoscopic procedures).

A wide array of endoscope makes and models are available.6 Cost-effective endoscopes are often portable and can be linked to phones or tablets for viewing (Figure 6), whereas more expensive models have limited mobility but are equipped with better light and camera sources and oxygen and suction attachments. When using endoscopes that provide oxygen supplementation, team members must be aware that the supplementation does not protect the airway from aspiration or allow positive pressure ventilation. Alveolar damage also could occur if an endoscope delivering oxygen is wedged into a bronchus.7

Figure 4

A scope fed through the ETT

Advanced Techniques

When basic orotracheal intubation is not possible or interferes with treatment, several options are available.

Temporary tracheostomy (Figure 7) is performed most commonly in patients with severe or life-threatening obstructions. Tracheostomy also reduces the amount of equipment in and around the oral cavity, so surgery is unhampered. Side effects include infection, hemorrhage, mucoid plugs, granulomas, strictures, dysphagia, and tracheal malacia.8-9

Lateral pharyngotomy (Figure 8) is another technique for avoiding oral intubation. The tips of a closed Carmalt forceps are inserted through the oropharynx and pushed laterally just caudal to the mandibular curvature. A visual tenting of the skin will indicate the location of the Carmalts. The skin is incised over the forceps tips, and the endotracheal tube is pulled through the neck and out the mouth with the forceps. The tube tip is then redirected into the trachea.

Retrograde intubation (Figure 9) is rarely used with patients in distress because other techniques allow faster control of the airway; however, the technique is an option when oropharyngeal anatomy is irregular. This technique involves inserting an intravenous catheter through the ventral aspect of the neck percutaneously into the trachea and directed rostrally. Then, a guide wire is inserted through the catheter and fed rostrally out the laryngeal aperture and mouth. An endotracheal tube is fed over the guide wire in the mouth through the laryngeal aperture into the larynx while stabilizing the wire in place. The catheter and the guide wire are removed from the tracheal while the ETT is advanced fully into the trachea.

Figure 7

Tracheostomy bypasses upper airway obstructions or restrictions and provides a direct route into the trachea.

Conclusion

Be ready for most airway encounters by learning these alternative techniques for intubation or airway control. Then, remain calm, be prepared with all the necessary equipment (Figure 10, above) and be ready to move to the next level to help ensure the success of each technique. Remember persistent planning prevents poor performance.