Urinary catheterization is commonly performed in veterinary patients for diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring.1 Indwelling urinary catheters allow for continuous urine collection and output assessment, as well as management of patients with urinary obstruction or bladder dysfunction, patients that are immobilized, and patients undergoing genitourinary surgery.1,2 Indwelling catheters are commonly used but are associated with complications (incidence, up to 50%) that should be prevented and monitored.1

Following are the top 5 complications associated with indwelling urinary catheters, according to the author.

1. Inflammation/Stricture Caused by Indwelling Urinary Catheters

Urinary catheters are made from a variety of materials, including silicone, latex, and coated latex.3 The ideal catheter material is unknown, but minimization of inflammation, trauma, and complications should be considered during catheter selection.3 All catheters can cause inflammation, partly due to material properties (eg, stiffness).3,4 Silicone catheters are more resistant to kinking and caused less inflammation in experimental models compared with latex catheters.4,5 The rigidity of polypropylene catheters can cause significant inflammatory lesions in the urethra and bladder.6

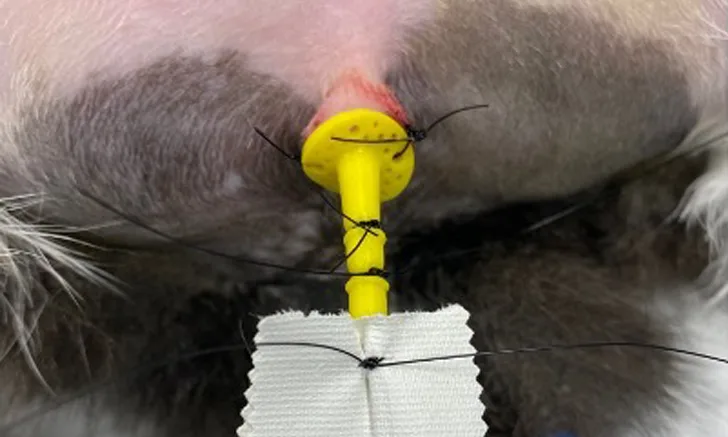

Catheter movement is also associated with urethral inflammation and should be avoided by securing indwelling catheters to prevent urethral traction (Figure 1).3

Properly secured urinary catheter in a cat. The catheter is sutured to the prepuce, sutures are placed around the catheter, and waterproof tape is placed over the remaining portion of the catheter to prevent slipping or movement.

Catheterization and trauma from inappropriate equipment or force can cause urethral strictures that may result in ongoing clinical signs and necessitate surgical intervention.7

Repeated catheterization can increase risk for urethral inflammation and stricture.7 An appropriately sized catheter should thus be placed using minimal force and the fewest possible attempts.

2. Urinary Tract Trauma/Rupture Caused by Indwelling Urinary Catheters

Trauma to the urethra or bladder can occur because of force, improper stylet positioning, and/or inadequate lubrication during catheterization.1

Catheter type and placement may also affect incidence of and risk for trauma. The rigidity of polypropylene catheters can make them easier to place but also increases risk for trauma.3 An appropriately sized soft catheter should be used.

Proper positioning of the patient, sedation, and technique are essential during placement to minimize risk for trauma.3 Patients can be positioned in any recumbency, but sternal recumbency is often preferred in female dogs and cats because anatomic landmarks, including the urethral papilla on midline and on the pelvic floor, can be easier to access in this position. Male cats are often placed in dorsal recumbency. Sedation is commonly needed for patient comfort and to avoid urethral spasms.1 Risk for urinary tract trauma and rupture is often increased in cases of urethral obstruction; hydropulsion (not passage of a urinary catheter) is recommended to remove obstructive material.7

3. Hematuria Caused by Indwelling Urinary Catheters

Macroscopic or microscopic hematuria can occur with urinary catheterization in human and veterinary patients.8 Hematuria can be secondary to UTI or sterile cystitis or be associated with catheter-related bladder and urethral irritation. Hematuria is common in catheterized patients regardless of underlying etiology but may result in premature removal of indwelling catheters in cats with urethral obstruction.9 The catheter should be removed if there is acute onset or clinical worsening of hematuria during indwelling catheterization.

4. Infection Associated with Indwelling Urinary Catheters

Catheter-associated bacteriuria (ie, positive culture results for one species of bacteria at a level of 103 colony forming units with no clinical signs of a UTI) is common in human and veterinary medicine; monitoring and treatment are not recommended for subclinical cases.1,2 Catheter-associated UTIs include positive urine cultures with additional signs of UTI, including fever or additional systemic and lower urinary tract signs.1,2 Incidence of catheter-associated UTIs may be >50% in veterinary patients; one study reported 20% incidence following one-time catheterization in female dogs.1,10 Catheter-associated UTIs occur secondary to introduction of microorganisms into the bladder, either during placement or during indwelling catheterization and maintenance.1 These infections can result in severe systemic complications (rare), including bacteremia and sepsis.11,12

Although some studies found patient sex to be associated with risk for catheter-associated UTIs, other studies demonstrate sex is not associated.11-13 There are no identified breed predispositions.11-13 Other factors, including age, have been associated with increased risk for catheter-associated UTIs; one study demonstrated a 20% increase in risk per year of age.14

Catheter type and maintenance, duration of catheterization, and previous or current antibiotic use can affect infection. All catheters, including those coated with antimicrobials, are vulnerable to infection and biofilm formation.3 Studies have demonstrated marked bacterial adherence and biofilm adherence to red rubber catheters compared with other materials.15 Foley catheters are most commonly used and are recommended for ongoing, indwelling urinary catheters. Increased duration of catheterization can also increase risk for UTI. In one study, incidence of catheter-associated infection increased by 27% each day a catheter was maintained following placement.1,14

Aseptic technique and veterinary staff training can help lower risk for infection during catheter placement, maintenance, and care. Patient preparation should include clipping fur in a 5-cm area around the vulva or prepuce, aseptically preparing the skin with diluted chlorhexidine 0.05% or iodine, and flushing the vestibule or prepuce 5 times with sterile water or saline.1,3 Sterile gloves should be worn and catheter sterility maintained during placement. Once placed, the catheter should be secured to reduce movement associated with inflammation and increased risk for infection.3 In addition, routine replacement of the catheter or collection system should be avoided.3,14

Use of a closed urinary collection system is recommended (Figure 2), and care should be taken to avoid urine reflux into the bladder and contamination of the urine bag, which should never be disconnected.1 Closed urine drainage systems facilitate aseptic emptying of the bag without disconnection to reduce risk for ascending infections.3 Open collection systems (eg, sterile empty fluid bag with macrodrip set) have not been associated with increased risk for nosocomial infection, but aseptic technique is essential.6

Closed collection system for an indwelling urinary catheter

Appropriate catheter care includes proper hand hygiene and wearing examination gloves when handling catheters and drainage.3 The catheter and external genitalia should be gently cleaned with chlorhexidine scrub and sterile water, and the prepuce and vestibule should be rinsed and flushed with diluted chlorhexidine every 6 to 8 hours as well as when visibly soiled.1

Antibiotic administration in patients with indwelling urinary catheters may increase risk for catheter-associated infections; routine use of antibiotics in these patients is therefore not recommended unless a documented UTI is present.1 Prophylactic antibiotics have been associated with a 454% increase in risk for catheter-associated UTI.14 Antibiotics should therefore be reserved for patients with documented infection.

The incidence of catheter-associated UTI is up to 55% in some studies.14 Routine culture of urine is not recommended, as catheter-associated bacteriuria without clinical signs should not be treated. Clinical signs, including fever, systemic illness, or CBC abnormalities, should prompt further clinical investigation for catheter-associated UTIs.

5. Mechanical Difficulties of Indwelling Urinary Catheters

Mechanical difficulties of indwelling urinary catheters include kinking and knotting. Kinking is not often described but has been associated with forceful catheterization and excessive catheter length.16,17 Knotting can cause significant morbidity in human and veterinary patients and may be caused by small catheter size, bladder overdistention, or placement of a catheter >10 cm within the bladder lumen.16,17 Management of kinking and knotting can be challenging, and several therapeutic techniques (eg, sustained traction under general anesthesia, untangling with a guidewire, endoscopic retrieval, open cystotomy) have been described.17-19

Foley catheters can cause unique complications related to overfilling the balloon, which may obstruct the catheter lumen secondary to compression of the catheter.1

Methods to decrease risk for mechanical difficulties include use of appropriate catheter size and length and reducing excessive catheter lumen in the urinary bladder. Catheter length should be measured prior to placement, and confirmation of proper placement with radiography can be considered.

Conclusion

Catheter-associated complications can result in patient morbidity and mortality. Incidence of common complications can be reduced by using an appropriate type and size of catheter, placing and maintaining the catheter correctly, and minimizing duration of catheterization.

Listen to the Podcast

Dr. Walton joins the podcast to dive deeper into the potential complications of urinary catheters and offers helpful tips to avoid them.