Interpretation of Serum Transaminase Levels in Dogs & Cats

Profile

DEFINITIONMeasurement of serum ALT and AST levels is a highly sensitive screening test for hepatobiliary disease.

ProblemsThe sensitivity of serum transaminases must be considered in light of the fact that serum ALT and AST activity can be increased under conditions in which the liver is not the primarily diseased organ. One report has noted that the positive predictive value of a twofold increase in serum ALT activity to detect primary liver disease is only 29%.1 The liver receives a rich blood supply from both the arterial and portal venous systems and is a dynamic metabolic organ with various functions, including fat digestion, intermediary metabolism, and detoxification of endogenous and exogenous compounds. Extrahepatic systemic disorders and diseases in organ systems drained by the portal circulation-particularly the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas-can damage the liver and increase levels of serum ALT and AST. Thus, under these conditions, increased liver enzymes may not reflect the presence of clinically important hepatic disease (Table 1). In addition, in dogs corticosteroids and phenobarbital can increase serum transaminase activity, particularly that of ALT, due to enzyme induction.2-6 It should be noted, however, that corticosteroids and phenobarbital can also increase serum ALT and AST activity due to hepatotoxicity.2-6

Serum transaminase levels increase when active disease causes hepatocyte membrane damage. However, since the liver has a huge regenerative capacity and great functional reserve, the magnitude of elevation in serum ALT or AST is not indicative of the extent of functional impairment and thus has limited prognostic value. In fact, ALT or AST elevations may be quite mild in severe end-stage liver disease because of enzyme depletion secondary to replacement of hepatocytes by fibrous tissue. For these reasons, a single serum ALT or AST measurement should never be used to make a definitive diagnosis or to establish a prognosis. The clinical significance of increased serum ALT or AST activity is improved by (1) monitoring for sequential enzyme elevations; (2) assessing for concurrent increases in other serum markers of liver disease (serum alkaline phosphatase, serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, serum bilirubin); (3) measuring liver function (serum total bile acids); and/or (4) obtaining a liver biopsy.

Incidence/PrevalenceElevations in serum ALT or AST are commonly noted on serum biochemical profiles in dogs. In a study of 261 dogs presented for various disorders to a referral hospital, 47% had elevations in ALT.7 In another study of 1022 blood samples from both healthy and sick animals submitted to a private veterinary laboratory, elevations in ALT and AST were seen in 20.3% and 12.1%, respectively.8

SignalmentIncreases in ALT or AST may indicate breed-related hepatopathies in Doberman pinschers, cocker spaniels, Labrador retrievers, Bedlington terriers, dalmatians, and Skye terriers. In addition, serum transaminase levels may be mildly elevated in dogs with congenital vascular diseases, such as portosystemic vascular anomalies or primary hypoplasia of the portal vein, disorders with distinct breed predispositions.9

Cause/Risk Factors/Pathophysiology

ALTIn most situations, ALT is considered a liver-specific enzyme in dogs and cats. In dogs, severe muscle necrosis can increase serum ALT, but a muscle source for the enzyme can be eliminated by simultaneous measurement of serum creatine kinase.10

Elevations in serum ALT are associated with reversible or irreversible damage to the hepatocyte plasma membrane. Increased serum ALT activity has the highest sensitivity (80% to 100%) for inflammation, necrosis, vacuolar hepatopathy, and primary neoplasia. Reduced sensitivity has been noted for the detection of liver failure due to feline hepatic lipidosis (72%), hepatic congestion (70%), metastatic neoplasia, portosystemic vascular anomalies, and secondary hepatic lipidosis (60%).1,11

The magnitude of serum ALT elevation is generally proportional to the number of injured hepatocytes. Since the t<sub1/2sub> in dogs is about 2.5 days, a 50% decrease over 2 to 3 days is a good prognostic sign. In cats, the serum t<sub1/2sub> is much shorter (around 6 hrs), so return to normal values after an acute insult occurs faster.

ASTCompared with ALT, AST is more sensitive but less specific for detection of hepatic disease.11 Serum AST is derived from liver, skeletal muscle, and cardiac muscle sources. In humans, there is both a cytosolic and mitochondrial liver isoenzyme, and this is presumably true in dogs and cats. The cytosolic enzyme is released with reversible or irreversible damage to hepatocyte plasma membranes and usually parallels increases in ALT. The mitochondrial enzyme is released only with irreversible hepatocyte injury.

Generally, the degree of serum AST elevation for a given amount of hepatocyte damage is less than the degree of ALT elevation. If serum AST is much higher than serum ALT, a muscle source of the enzymes should be explored. In humans, a disproportionate increase in AST over ALT is also seen in conjunction with severe, irreversible hepatocyte injury, in which large amounts of mitochondrial AST are released into the serum.12

The t<sub1/2sub> of AST in dogs and cats has been reported as 12 hours and 77 minutes, respectively. Because the t1/2 of serum AST is shorter in dogs than the t<sub1/2sub> for serum ALT, levels of the former enzyme generally return to normal faster. AST has been reported to be more sensitive than ALT for the detection of metastatic disease in the liver (70% to 95% vs 45%, respectively).13 Hemolysis also increases serum AST.

Diagnosis

To determine the clinical significance of persistently elevated levels of serum ALT or AST, the clinical scenario must be scrutinized as a whole. Historical information, clinical signs, physical examination findings as well as the results of diagnostic imaging and ancillary laboratory evaluation must be considered.

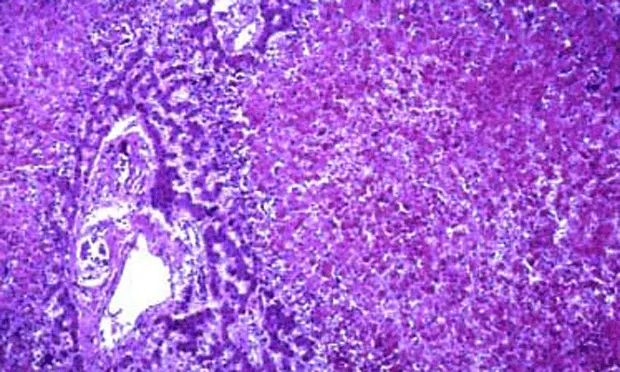

Acute hepatic necrosis in a 3-year-old German shepherd. Serum ALT and AST were 20 and 16 times the upper limits of normal, respectively.

HISTORY/PHYSICAL EXAMINATIONImportant aspects of the history and physical examination for liver disease are listed below.History of toxin exposure: Cycad seeds, mushrooms, blue-green algae bloomHistory of drug administration: See Table 2.14Polyuria/polydipsia: Hyperadrenocorticism, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, congenital portosystemic shunts, hyperthyroidism (cats)Dermatologic disease: Hyperadrenocorticism, hepatocutaneous syndromeDiffuse cerebral signs: Hepatic encephalopathy due to congenital or acquired portosystemic shuntsPot-belly: HyperadrenocorticismJaundice: Prehepatic (hemolytic anemia), hepatic, or posthepaticAbdominal effusion: Chronic liver disease with ascites, neoplasia, pancreatitis, congestive heart failureHepatomegaly: Primary liver disease, corticosteroid hepatopathy, passive congestion, neoplasia, hepatic lipidosis, amyloidosis, cirrhosis (cats)Dyspnea/increased lungs sounds: Congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism (cats)Abdominal pain: Blunt trauma, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, gastric ulcerationChronic intermittent gastrointestinal signs: Gastric ulceration due to chronic liver disease, congenital portosystemic shunts, chronic pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, hyperthyroidism, diarrhea (cats)Palpable thyroid nodules: Hyperthyroidism (cats)Tachycardia: Hyperthyroidism (cats)

IMAGINGRadiography• Hepatomegaly: See above.• Microhepatica: Cirrhosis (dog), congenital portosystemic shunts• Choleliths: 50% visible radiographically• Decreased abdominal detail: Ascites• Cardiomegaly with pulmonary edema/pleural effusion: Heart failure

UltrasonographyHepatobiliary• Focal or multifocal lesions: Primary or metastatic hepatobiliary neoplasia, nodular hyperplasia (common in older dogs), abscess• Diffusely hyperechoic liver: Hepatic lipidosis, corticosteroid hepatopathy, lymphosarcoma• Diffusely hypoechoic liver: Passive congestion, lymphosarcoma, suppurative hepatitis• Normal liver: Does not rule out primary hepatic disease• Gallbladder/biliary tree: Gallbladder mucocele or choleliths, distended biliary tree• Portal vasculature: Single congenital or multiple acquired portosystemic shunts, portal vein thrombosis, passive congestion

Gastrointestinal tractPancreas: Enlarged hypoechoic surrounded by hyperechoic fat indicative of pancreatitisThickened gastrointestinal tract: Inflammatory bowel disease or lymphosarcoma

Other abdominal organsPrimary neoplasia of spleen, stomach, pancreas, intestine, or adrenals accompanied by focal hepatic nodules

LABORATORY ANALYSISHyperadrenocorticism: In dogs, concurrent increase in serum alkaline phosphatase (induction of corticosteroid specific isoenzyme) that is much greater than the increase in serum transaminase levels; mild polycythemia and thrombocytosis, hypercholesterolemiaPrimary liver disease: Both ALT and AST increased together, +/- increases in serum alkaline phosphatase and serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, hypoalbuminemia, low blood urea nitrogen, hypoglycemiaChronic liver disease: Ascites that isa pure transudate with a total protein< 2.5 g/dlRight heart failure: Ascites that is amodified transudate with a total protein> 2.5 g/dlChronic gastrointestinal disease: Panhypoproteinemia, hypocholesterolemia, lymphopeniaAcute pancreatitis: Increased serum amylase and/or lipase (dogs); acute nonseptic inflammation on abdominal tapCancer: Malignant effusion on abdominal tap, high protein ascites with exfoliated cells, hemorrhagic effusion with ruptured hemangiosarcoma. Absence of neoplastic cells does not rule out a malignant effusion.

Definitive DiagnosisDrug toxicity: Stop drug and monitor serum enzyme activity.Hyperthyroidism: Serum total thyroxineHyperadrenocorticism: Failure to suppress on a low-dose dexamethasone-suppression test or an exaggerated response to an adrenocorticotropin-stimulation testPrimary hepatobiliary disease: Rule out concurrent disease causing reactive hepatopathy. Abnormal hepatic function test, elevated total serum bile acids, serum hyperbilirubinemia with normal packed cell volume, blood hyperammonemia, increased prothrombin or partial thromboplastin time, abnormal liver biopsyChronic gastrointestinal disease: Serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity, pancreatic lipase, endoscopy with intestinal biopsy, fine-needle aspiration or biopsy of the pancreasCancer: Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration

TreatmentTreatment is based on the determination of the cause of the increased transaminases.

DX at a glance...

Measurement of serum transaminase levels is the most sensitive screening test for the presence of hepatobiliary disease available to the small animal practitioner.

Serum ALT and AST elevations indicate active hepatobiliary disease, but provide no information on the functional state of the liver.

The prognostic significance of serum ALT/AST elevation can be improved by evaluating sequential tests, looking at concurrent increases in other serum markers of hepatobiliary disease (such as serum alkaline phosphatase, serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, albumin, bilirubin, and total serum bile acids), and using them in conjunction with diagnostic imaging findings +/- hepatic histopathology.

Serum ALT or AST can be elevated without the presence of clinically significant liver disease particularly in disorders affecting the gastrointestinal tract, in hyperthyroidism in cats, and during glucocorticoid or phenobarbital therapy in dogs.

INTERPRETATION OF SERUM TRANSAMINASE LEVELS • Cynthia R. L. Webster

References

1. Liver enzyme profiling: What works and what does not. Reyers F. World Small Anim Vet Assoc Congr Proc, 2003.2. Sequential morphologic and clinicopathologic alterations in dogs with experimentally induced glucocorticoid hepatopathy. Badylak SF, Van Vleet JF. Am J Vet Res 42:1310-1318, 1981.3. Comparison of serum biochemical and hepatic functional alterations in dogs treated with corticosteroids and hepatic duct ligation**.** DeNovo RC, Prasse KW. Am J Vet Res 44:1703-1710, 1983.

Effects of dexamethasone and surgical hypotension on hepatic morphologic features and enzymes in dog. Dillon AR, Sorjonen DC, Powers RD et al. Am J Vet Res 44:1996-1999, 1983.5. Thyroid function and serum hepatic enzyme activity in dogs after phenobarbital administration. Geiger TL, Hosgood G, Taboada J, et al. J Vet Intern Med 14:277-281, 2000.6. Effects of long-term phenobarbital treatment on the liver in dogs. Mueller PB, Taboada J, Hosgood G, et al. J Vet Intern Med 14:165-171, 2000.

Pre-operative liver screen selection: A comparison for serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase and serum alkaline phosphatase. Brunson DB, Stevens JB, McGrath CJ. JAAHA 16:209-214, 1980.8. Haematological and biochemical abnormalities in canine blood: Frequency and associations in 1022 samples. Comazzi S, Pieralisi C, Bertazzolo W. J Small Anim Pract 45:343-349, 2004.9. Association of breed with the diagnosis of congenital portosystemic shunts in dogs: 2400 cases (1980-2002). Tobias KM, Rohrbach BW. JAVMA 223:1636-1639, 2003.

Increased serum alanine aminotransferase activity associated with muscle necrosis in the dog. Valentine BA, Blue JT, Shelley SM, Cooper BJ. J Vet Intern Med 4:140-143, 1990.11. Diagnostic procedures for the evaluation of hepatic disease. Center SA. In Guilford WG, Center SA, Strombeck DR, et al (eds): Strombeck's Small Animal Gastroenterology, 3rd ed-Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1996, pp 130-188.12. Validity and clinical utility of the aspartate aminotransferase-alanine aminotransferase ratio in assessing disease severity and prognosis in patients with hepatitis C virus related chronic liver disease. Giannini E, Risso D, Botta F, et al. Arch Intern Med 163:218-224, 2003.13. Biochemical evaluation of metastatic liver disease. McConnell MF, Lumsden JH. JAAHA 19:173-178, 1983.14. Hepatotoxicity associated with pharmacologic agents in dogs and cats. Bunch S. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 23:659-669, 1993.