Imaging the Urinary Tract

Radiographic and ultrasound imaging—in addition to history, physical examination, and clinicopathologic testing—are often used to provide diagnostic information in dogs and cats with known or suspected urinary tract disorders. Although ultrasound has largely become the first-choice imaging modality for small animal urinary tract disease, radiographic imaging is complementary to ultrasonography; both should be employed to evaluate cases whenever possible.

Kidneys

Survey abdominal radiographs (Figures 1 and 2) offer important information on kidney number, size, shape, symmetry, and location, as well as the presence of any mineralized opacities (eg, calcified tissue, nephroliths). The utility of abdominal radiographs is decreased in patients with abdominal fluid or lack of abdominal fat (eg, young or emaciated patients) because of lack of contrast. Excretory urography (IV pyelography), although more invasive, can augment survey radiographs and provide information about renal parenchymal architecture (eg, filling defects associated with cysts or infiltrative disease), the renal pelvis, and ureters as well as a qualitative assessment of global and individual renal excretory function (Figure 3).

Similar to survey radiography, ultrasonography can document the number, size, shape, and location of the kidneys as well as the presence of mineralized tissue and nephroliths. In contrast to radiography, abdominal fluid or lack of abdominal fat does not limit the utility of ultrasound. The major advantage of ultrasound for evaluating kidney disease is its ability to assess the internal renal architecture and perirenal tissues. Both focal and diffuse lesions are recognized. Focal lesions may be solid, either homogenous or heterogenous, or fluid in nature. Diffuse lesions (Figures 4-8) may uniformly affect the parenchyma or be heterogenous. The renal cortex, medulla, or both regions may be affected depending on the disease process.

Related Article: Feline Polycystic Kidney Disease

Renal pelvic dilation (pyelectasia) and proximal ureteral dilation are readily observed with ultrasound and renomegaly may be seen on radiographs if dilation is severe (Figures 9 and 10). Ultrasound can also be used to guide fine-needle aspiration and tissue biopsies of the kidney and fluid aspiration from a dilated renal pelvis. The major limitation of ultrasonographic evaluation of the kidneys is operator experience and expertise.

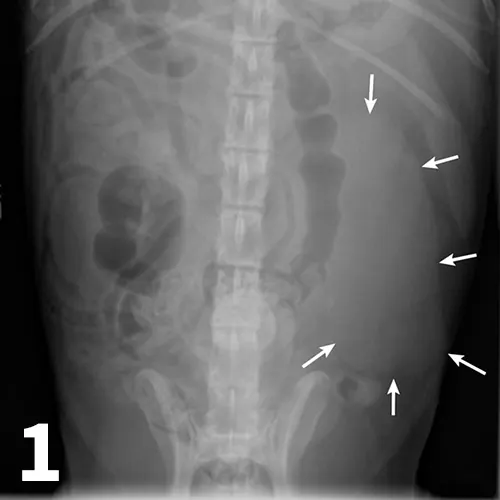

Figure 1.

An enlarged left kidney with an irregular shape (arrows) is noted on the VD view of a dog with renal adenocarcinoma. The left kidney measured 4.5 times the length of L2; normal kidney length in the dog is 2.5 to 3.5 times the length of L2.

Ureters

Normal ureters cannot be visualized with survey radiography or ultrasonography, but normal and abnormal ureters are readily visualized with excretory urography. The location of a ureteral obstruction or rupture as well as the presence of an ectopic ureter (especially when combined with pneumocystography) can be documented with excretory urography (Figure 11). A dilated ureter (hydroureter) can be observed with ultrasonography (Figure 12). Pyelocentesis (for cytology and culture) and antegrade pyelography (nephropyelography) (Figure 13) to document obstruction or leakage can be conducted via ultrasound guidance with heavy sedation or anesthesia. Ultrasonography can also be used to visualize retroperitoneal fluid accumulation, which may occur with a ureteral rupture, hemorrhage, or infectious or neoplastic disease. Whereas ureteroliths without hydroureter may be missed on ultrasonography, radiopaque ureteroliths can be observed on survey radiography (Figure 14). Survey radiographic visualization of radiopaque ureteroliths may be facilitated by enemas to empty the colon of fecal material and/or use of a radiolucent paddle to apply regional compression over the ureter to separate adjacent organs (eg, loops of bowel) (Figure 15). Aged cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD) frequently have calcium oxalate nephroliths; in some cases, these nephroliths will migrate into the ureters. Survey radiographs should be employed to rule out ureterolithiasis, especially in cats with acute decompensation of their CKD (Figure 16).

Related Article: Endourology: A New Way of Looking at Things

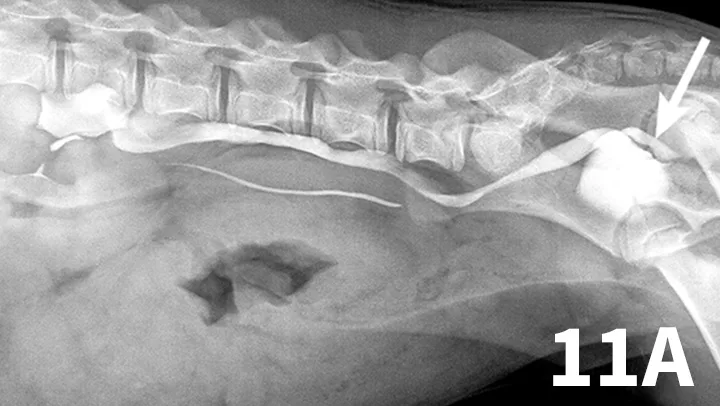

Figure 11A.

Lateral oblique view from a young dog with a left ectopic ureter that was diagnosed with excretory urography. The left ureter and renal pelvis are dilated. The left ureter extends beyond the trigone region of the urinary bladder on the lateral oblique view (arrow).

CKD = chronic kidney disease

Urinary Bladder

Survey radiographs of the urinary bladder are helpful for evaluation of size and location and for detection of radiopaque calculi. Urinary bladder distention is readily detected (Figure 17). Radiographs are of limited value in evaluating mural disease because the bladder wall cannot be differentiated from the fluid contained within the bladder. Bladder wall thickening (eg, bacterial inflammation, polypoid cystitis, neoplasia) is best evaluated by ultrasonography or double-contrast cystography (Figure 18). It should be noted that the degree of bladder filling can affect bladder wall thickness. For example, a small, mildly distended bladder may appear to have a thickened bladder wall on ultrasound compared with a moderately or severely distended bladder (Figure 19). This potential disadvantage can often be overcome by reevaluating the bladder several hours after preventing voiding.

Related Article: Differentiating Canine Urinary Tract Infections

Double-contrast cystography can be an excellent tool to evaluate bladder wall thickness and any irregularities of the bladder mucosal surface and to rule out the presence of radiolucent cystouroliths (Figure 20). Although double-contrast cystography is more invasive because of the need for urethral catheterization, artifactual bladder wall thickening is usually not an issue because the degree of bladder distention can be controlled.

Positive-contrast cystography is useful when evaluation of urinary bladder location or integrity is questioned (Figures 21 and 22).

Related Article: Urethral Blockage in a Male Cat: Much More Than Expected

The major advantage to survey radiography of the urinary bladder is the detection of radiopaque cystouroliths. In many cases, the radiodensity, size, and shape of the uroliths aid in determining urolith type, which is not possible with ultrasonography (Figures 23 and 24), but type of urolith cannot be definitively determined with radiography. Ultrasonography has the advantage of detecting radiolucent cystouroliths (Figure 25). Emphysematous cystitis can be observed on both survey radiography and ultrasonography (Figure 26). Standing the patient may be useful when trying to determine if a bladder abnormality is within or adhered to the wall or free within the lumen (hematoma or calculi) (Figure 27). Ultrasonography has the advantage of allowing evaluation of sublumbar lymph nodes and other perivesicular structures as well as enabling cystocentesis when the bladder is small and minimally distended. Extension of neoplasia to the spine, as with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, is more easily identified with radiography.

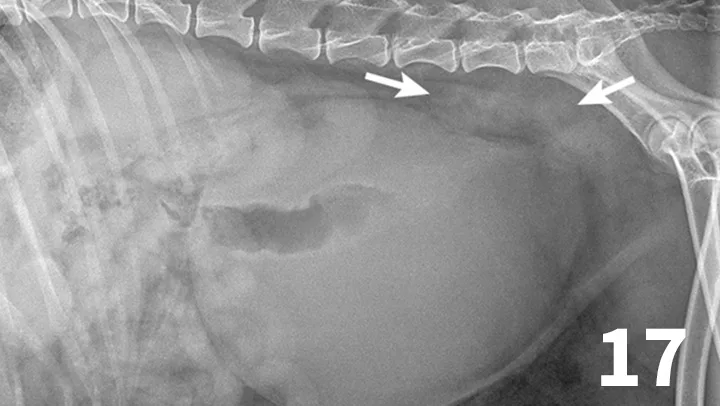

Figure 17.

This dog had a severely distended urinary bladder on evaluation of lateral abdominal radiographs. Ill-defined, soft tissue opacity was present in the region of the medial iliac lymph nodes (arrows). The dog had urethral neoplasia, which was the cause of the urinary outflow obstruction and lymph node enlargement.

Urethra

The normal urethra of dogs and cats is difficult to visualize on survey radiography and ultrasonography. Radiopaque urethroliths can be observed on survey radiographs, and therefore the entire urethra should always be included in the field of view (Figure 28). In male dogs, it is useful to pull the hindlimbs forward to assess the urethra between the pelvis and os penis (Figure 29). The prostate gland and proximal urethra, before entering the pelvic canal, can be visualized with ultrasonography, especially if there is urethral distention. In male dogs, the urethra at the proximal os penis can be evaluated with ultrasonography to assess for urethroliths, which commonly lodge in this location. Positive-contrast retrograde urethrography is the best tool for diagnosis of intraluminal, intramural, and extramural compressive urethral disorders as well urethral rupture (Figure 30).

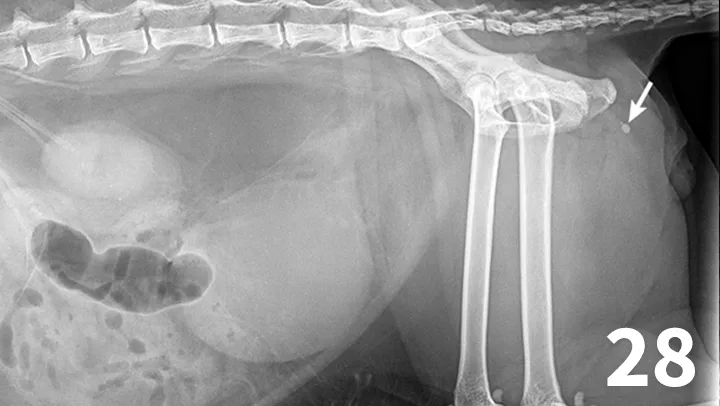

Figure 28.

There are 1 small and 1 large round urethral calculi (arrow) in this cat with urinary obstruction. The bladder is severely distended, and there is decreased detail caudal to the bladder. This demonstrates the importance of including the entire urethra on radiographs when urinary bladder obstruction is present or suspected.

Prostate Gland

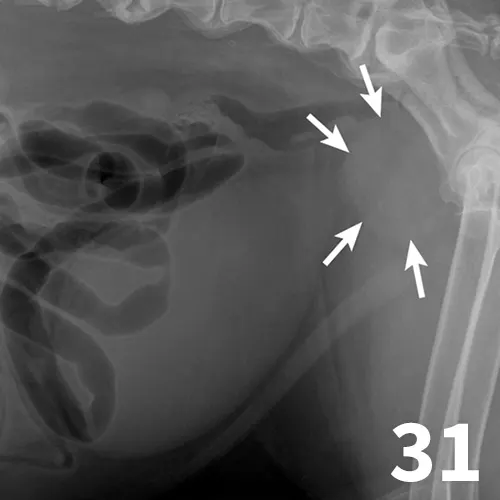

Survey radiography can be used to evaluate the size, shape, and opacity of the prostate gland (Figures 31 and 32). Ultrasonography has the advantage of providing tissue-architecture information. Prostatic abscesses, internal cysts, and paraprostatic cysts are readily visualized on ultrasonography. Ultrasonography can also aid in diagnosing benign hyperplasia (homogenous echotexture with intact capsule) and prostatic neoplasia (heterogenous with course echotexture and irregular margins) (Figure 33) and with identifying any potential source of excess androgen production (eg, adrenal glands, retained testes) in cases of suspected squamous metaplasia of the prostate gland. Mineralization of the prostate in a neutered dog is suggestive of neoplasia and can be detected by both survey radiography and ultrasonography. Sublumbar lymph nodes can also be evaluated by ultrasonography, whereas radiography is best for evaluating the adjacent lumbar spine (Figures 34 and 35).

Related Article: Prostatic Disease

Figure 31.

The prostate gland (arrows) in this intact male dog is enlarged but normal in shape with smooth margins and soft tissue opacity. Although this is consistent with benign prostatic hypertrophy, ultrasound would be useful to further define tissue architecture.

Conclusion

Radiography and ultrasonography have distinct advantages and weaknesses in the evaluation of urinary tract disorders in dogs and cats. Combining these 2 imaging modalities will almost always provide improved diagnostic information compared with the use of 1 modality alone.

LAURA ARMBRUST, DVM, DACVR, is professor of radiology at Kansas State University. Dr. Armbrust has clinical and research interests in all types of diagnostic imaging. She was in mixed animal practice in Wisconsin for 2 years. She completed her residency and board certification in radiology at Kansas State University, her alma mater.

GREGORY F. GRAUER, DVM, MS, DACVIM, is professor and Jarvis chair of medicine in the clinical sciences department at Kansas State University. His area of interest, research, and teaching is the small animal urinary system. A graduate of Iowa State University, he has served as professor and section chief of small animal medicine at Colorado State University and faculty member at University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he completed his internship and residency and earned his master’s.