Urinalysis, which can easily be performed in-house, is helpful in establishing baseline data, especially for comparison with ongoing clinicopathologic data for dogs and cats with clinical signs of urinary tract disease. Preferred collection methods include free-catch, cystocentesis, and catheterization. Ideally, urine should be examined within 30 minutes of collection. If analysis is delayed, containers should be protected from exposure to UV light and tightly capped. Urine can be stored in the refrigerator for up to 24 hours, but refrigerated samples should reach room temperature prior to analysis.

Color and turbidity of urine should be evaluated before centrifugation. Specific gravity can be measured by refractometry on a turbid sample with or without centrifugation, but turbid urine should be centrifuged prior to chemical analysis with commercial reagent strips.

Complete urinalysis includes microscopic examination of urine sediment, prepared by centrifuging a standard volume of urine (10mL) at 1500 rpm for 5 min, decanting the supernatant, and resuspending the sediment by gently tapping on the tube. The sediment can be evaluated with or without staining. Using freshly collected urine and precipitate-free stain results in fewer artifacts. A drop of the sediment is placed on a glass slide and covered with a coverslip. Improved contrast of the sediment is achieved by lowering the condenser and partially closing the iris diaphragm. Low-power (100×) magnification is used to identify casts, crystals, cells, sperm, mucus, and lipid droplets. High-power (400×) magnification is used to identify erythrocytes, leukocytes, epithelial cells, microorganisms, and crystals. Results are recorded as number of elements per low-power field (/lpf) or per high-power field (/hpf).

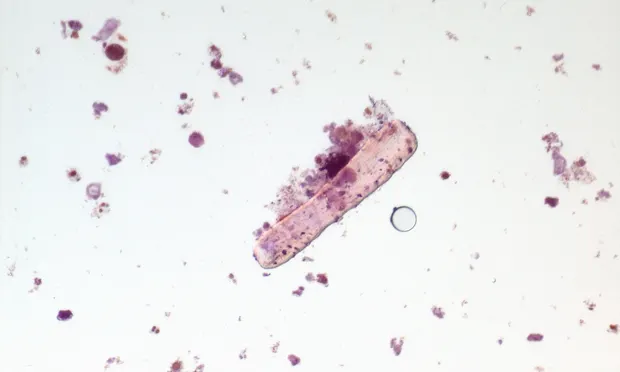

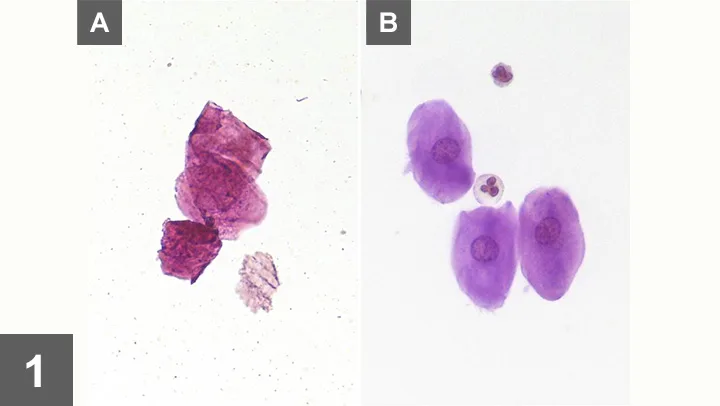

FIGURE 1

(A and B).

Squamous epithelial cells (400×, Sedi-Stain).

Squamous epithelial cells originate from the urethra, vagina, or prepuce and have no clinical significance. Their numbers typically are higher in samples obtained by catheterization as compared with free-catch samples; squamous epithelial cells normally are not present in samples obtained by cystocentesis. Squamous epithelial cells are large polygonal cells that either are anucleate (A) or have small nuclei (B).