Hypoglycemia

Thomas Schermerhorn, VMD, DACVIM (SAIM), Kansas State University

Hypoglycemia is a manifestation of a pathologic process—not a diagnosis. It is always secondary to a disorder that disrupts or overwhelms one or more of the homeostatic mechanisms responsible for maintenance of normoglycemia.

Background & Pathophysiology

Glucose is a dietary carbohydrate used as a substrate for adenosine triphosphate production via anaerobic and aerobic pathways. Its use as a cellular source of fuel requires regulation at multiple points during metabolism. As a result, glucose homeostatic pathways are highly integrated to maintain blood glucose levels within precise physiologic limits.1

Hypoglycemia is defined as a decrease in blood glucose below the physiologic range and is considered clinically relevant when levels decrease below 60 mg/dL.2

Blood Glucose Regulation

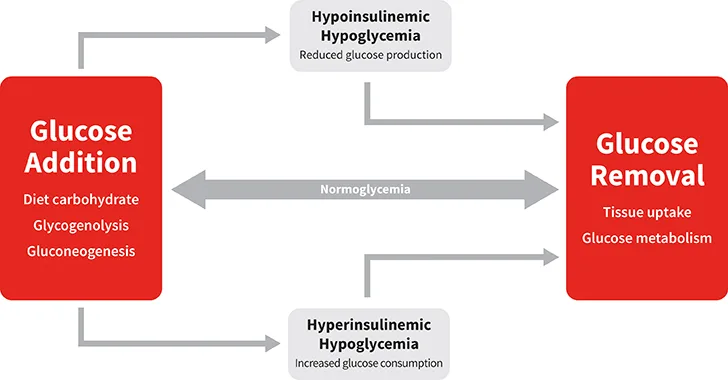

Normoglycemia is maintained by the actions of multiple hormones that regulate the metabolic pathways responsible for glucose addition and removal from blood (Figure). Insulin and glucagon are the most important hormones involved in glucose homeostasis. The major pathways through which glucose is added to blood are intestinal absorption of dietary glucose and hepatic glucose production via glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.3 Insulin and glucagon play opposite roles in blood glucose regulation. Insulin exerts hypoglycemic effects through actions that stimulate glucose uptake by target tissues and reduce hepatic glucose output.3 Glucagon has no effect on cellular glucose uptake but potently increases the rate of glucose appearance in blood through stimulation of glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.4 It is the balance of these hormones—the insulin:glucagon ratio—that determines whether there is a net gain or loss of glucose from blood.

When glucose decreases below its physiologic set point, insulin secretion is typically inhibited and glucagon secretion is stimulated; when the decrease in glucose levels is rapid, a marked counterregulatory response serves to rescue the organism from severe hypoglycemia.5 The counterregulatory response is mediated through the actions of hormones such as cortisol and other glucocorticoids, catecholamines, and growth hormone, which induce a degree of insulin resistance that helps increase blood glucose. Hypoglycemia occurs when the rate of glucose removal exceeds the rate of its addition to blood.1 Endogenous or exogenous substances that mimic or potentiate insulin action or enhance or accelerate glucose metabolism increase glucose removal, whereas failure of endogenous glucose production decreases the rate of glucose addition to blood. Disruptions of the pathways responsible for glucose addition or removal may overwhelm homeostatic mechanisms and produce clinical hypoglycemia.

Normoglycemia represents balance between glucose addition and removal from the blood. Hypoglycemia results when the rate of glucose addition falls below the removal rate (ie, hypoinsulinemic hypoglycemia) or when the rate of removal exceeds the addition rate (ie, hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia).

Mechanisms of Action

Hypoglycemia has been associated with a variety of clinical conditions but is a consistent feature of relatively few disorders. Because artifactual and factitious causes for hypoglycemia are fairly common, it is important to rule out the possibility of preanalytic (eg, improper sample collection, handling or storage) or analytic (eg, inaccurate glucometer) errors before accepting the validity of a test result consistent with hypoglycemia, especially when clinical signs are lacking or the finding is unexpected. Confidence in the result can be improved by repeating the analysis or using a different technique to measure glucose. Clinical disorders produce hypoglycemia through one or more pathophysiologic mechanisms. Clinical hypoglycemia can be broadly divided into several categories: hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, hypoinsulinemic hypoglycemia, and miscellaneous disorders (Table 1).6

Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia is the most common mechanism of hypoglycemia in dogs and cats, with relative or absolute insulin excess being a common feature (Table 1). Exogenous insulin administered to diabetic patients is responsible for most cases of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in veterinary medicine; typically, the cause is insulin overdose, although pharmacologic doses of insulin given to diabetic cats may result in onset of diabetes remission with subsequent hypoglycemia.7,8 Accidental or nefarious injection of insulin has been described in nondiabetic humans but is an unlikely cause of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in animals.9

Table 1: Pathophysiologic Mechanisms & Major Causes of Hypoglycemia

Insulinoma, a neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas, is the most common disorder associated with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia due to excess production of endogenous insulin.10 Insulin excess due to islet cell hyperplasia has been suspected in some dogs.11,12 In humans, oral hypoglycemic drugs (eg, sulfonylureas) that stimulate release of endogenous insulin can cause hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. However, these drugs are infrequently used in veterinary medicine, so this effect is unlikely to be encountered clinically.13

Ingestion of xylitol, an artificial sweetener used in many products intended for human use, causes profound hypoglycemia in dogs.14 Uniquely in dogs, xylitol is a potent stimulator of insulin release, and toxicity occurs after ingestion of more than 0.1 g/kg.15,16 Hypoglycemia results from insulin excess with or without concurrent failure of hepatic glucose output, which is caused by xylitol-induced liver damage.

Hypoinsulinemic hypoglycemia describes hypoglycemia that develops independent of insulin; in associated conditions, blood insulin is appropriately low with hypoglycemia. Non-insulin–mediated hypoglycemia may develop via one of several mechanisms (Table 1). Several tumor types (eg, hepatomas, hepatocellular carcinomas, leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas) produce humoral insulin-like substances (eg, insulin-like growth factor-1) that promote hypoglycemia.2,6,17 Hypoinsulinemic hypoglycemia can also occur with disorders that increase use of glucose by body tissues or those associated with failure of hepatic glucose production.18

History & Clinical Signs

Hypoglycemia is a manifestation of disease rather than a specific diagnosis. Patient age and breed, previous diagnoses (eg, diabetes), and information about the conditions that elicit signs (eg, fasting, exercise) provide clues about possible causes. Patients may not share a consistent history except when the only signs displayed are those of hypoglycemia. Signs of hypoglycemia can be divided into signs related to impaired tissue energetics (neuroglycopenic) and those related to sympathetic activation (neurogenic; see Signs of Hypoglycemia).19 Acute hypoglycemia can produce a variety of nonspecific signs, including muscle tremors or weakness, ataxia, nausea, vomiting, behavior changes, confusion, collapse, seizures, and coma.2 Chronic or intermittent hypoglycemia is often associated with vague signs of decreased activity or reduced energy, which may be accompanied by signs that are usually associated with acute exacerbations.19

Signs of Hypoglycemia19

Signs may be triggered under such circumstances as fasting, stress, or exercise.

Severity of signs depends on hypoglycemia duration and severity.

Marked hypoglycemia may be tolerated in dogs and cats with chronic or episodic hypoglycemia.

Neurogenic Signs

Restlessness

Hunger/food seeking

Nausea/vomiting

Tachycardia

Tremors

Signs reported in humans include feeling shaky, sweating, and anxiety, but equivalent signs are difficult to define in dogs and cats.

Neuroglycopenic Signs*

Weakness

Unusual behaviors, confusion, apparent vision abnormalities

Ataxia

Lethargy

Seizure

Coma

*Severe or prolonged neuroglycopenia may be fatal.

Diagnosis

Hypoglycemia is diagnosed when the measured blood glucose level is below the reference range, which is generally centered around 90 to 100 mg/dL and ranges from 70 to 120 mg/dL. Clinically, signs are most likely to appear when the glucose level is ≤60 mg/dL.2,19 Hypoglycemia may be documented using a variety of clinical testing methods, including serum chemistry profile, whole blood testing using a portable glucometer, or interstitial fluid analysis using a continuous glucose monitor. Artifactual hypoglycemia is a preanalytic error that occurs when glucose in the sample is consumed by blood cells during processing. Some examples include consumption by RBCs when clot removal is delayed during serum processing or by WBCs when severe leukocytosis is present.20 If laboratory error is eliminated as a cause, persistent or recurrent hypoglycemia should be investigated. Because recognition of hypoglycemia per se is not sufficient to make a diagnosis, patient history, physical examination, and other diagnostic findings must be carefully evaluated to identify the underlying cause. A diagnosis of clinically relevant hypoglycemia is confirmed by satisfying the criteria of Whipple’s triad: 1) clinical signs of hypoglycemia, 2) concurrent biochemical hypoglycemia, and 3) resolution of clinical signs with correction of hypoglycemia. In many cases, a series of diagnostic tests and imaging studies are needed to identify an underlying cause for hypoglycemia.

Treatment & Management

Treatment aims to eliminate the clinical signs of hypoglycemia and address any underlying pathology (Table 2). Mild hypoglycemia may be alleviated by feeding, especially in young animals or small-breed dogs in which hypoglycemia may develop due to rapid depletion of glycogen. Blood glucose can be increased rapidly via oral or IV glucose supplementation. Oral glucose is usually provided as corn syrup or honey, both of which contain large amounts of glucose in the form of simple sugars.19 IV glucose is usually supplied via bolus injection or CRI of a glucose solution prepared from a sterile 50% dextrose solution. Infusion of glucagon, a hormone that antagonizes insulin-mediated inhibition of gluconeogenesis and promotes hepatic glucose production, has been used to treat hypoglycemia associated with insulin overdose and insulinoma in dogs.21,22

Some medications are useful for addressing chronic hypoglycemia associated with specific disorders. Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone, dexamethasone) are used as replacement therapy for cortisol deficiency that accompanies hypoadrenocorticism.23 Given at doses sufficient to induce insulin resistance, these drugs are also used as adjunctive treatment for insulinoma-associated hypoglycemia.10 Anecdotally, L-carnitine supplementation may help ameliorate hypoglycemic events in susceptible small-breed puppies, including those with hypoglycemia caused by portosystemic shunting.

Table 2: Treatment of Hypoglycemia

Prognosis

Correction of hypoglycemia is readily accomplished with glucose supplementation. However, initial improvement will wane if the underlying pathology of hypoglycemia is not addressed or resolved. Frequent or continuous glucose supplementation may be needed to support patients with hypoglycemia caused by insulin overdose until the exogenous insulin is fully metabolized. Insulin excess due to insulinoma causes a similar problem, but release of endogenous insulin from insulinoma is ongoing and may be unpredictable. Some of these tumors may retain the ability to secrete insulin in response to hyperglycemia, which may develop during bolus glucose administration. The severity of hypoglycemic episodes experienced by juvenile animals or small-breed dogs may decrease with treatment and time as the animal matures and grows.

Idiopathic hypoglycemia carries a good prognosis if triggering factors can be identified and avoided. Prognosis for paraneoplastic hypoglycemia depends on whether effective treatment of the underlying neoplasm is possible. Hypoglycemia secondary to liver failure subsequent to cirrhosis or other disorders carries a poor prognosis, whereas hypoglycemia in patients with portovascular anomaly is expected to resolve after shunt closure.