Thoracic radiography is a common diagnostic imaging modality used for assessment of the cardiovascular system in dogs. The cardiac silhouette, great vessels, and pulmonary circulation are most commonly evaluated qualitatively, although some objective parameters reinforce subjective assessment and are particularly useful when evaluating serial radiographs over time and when aiming to predict a particular stage of heart disease. This article provides a practical guide on how to approach evaluation of the heart with thoracic radiographs, as well as case examples of common cardiac diseases in dogs.

Image Acquisition

At least 2 orthogonal views, ideally taken during peak inspiration, are necessary for appropriate radiographic study of the cardiovascular system; however, a 3-view study is ideal for comprehensive evaluation of the thorax. Some differences should be considered when deciding to acquire a right versus left lateral projection and a dorsoventral (DV) versus ventrodorsal (VD) projection. On the left lateral view, the cardiac silhouette is typically more rounded and the apex is further elevated from the sternum than in the right lateral view (Figure 1). In the DV view, the cardiac silhouette is commonly displaced cranially and to the left by the diaphragm and appears more rounded than in the VD view. The caudal pulmonary vasculature is better delineated in the DV view, whereas the lung field (particularly the accessory lobe) is better evaluated in the VD view (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1 Normal right and left lateral projections of the thorax in a large, crossbreed dog. The difference in the cardiac silhouette and the apex elevation (arrow) from the sternum in the left lateral view can be seen. VHS, VLAS, modified VLAS (M-VLAS), and VRHi collected from the right lateral view are 10.6, 1.7, 2.8, and 3, respectively, and 10.6, 1.5, 2.9, and 3.4, respectively, collected from the left lateral view. Given these differences, serial radiography should be performed using the same lateral view if only one view is used. In some dogs, roundness of the cardiac silhouette in the left lateral view can be pronounced and misinterpreted as right-sided heart enlargement, particularly if compared with a prior right lateral view. Images courtesy of Federico Villaplana Grosso, DACVR, DECVR

FIGURE 2 Normal DV (left) and VD (right) projections of the thorax in a large, crossbreed dog. The cardiac silhouette appears more rounded, and the caudal pulmonary vasculature is more apparent (arrowheads) in the DV view compared with the VD view. In some DV projections, the cardiac silhouette can appear significantly displaced to the left (not apparent in this case). Images courtesy of Federico Villaplana Grosso, DACVR, DECVR

Differences Among Dog Breeds

The size of the cardiac silhouette relative to the thoracic cavity can vary significantly among breeds and in patients with different BCS. This finding is supported by variation of the normal range of vertebral heart scale (VHS) among breeds.1-3 In general, deep-chested dogs have an elongated heart and a lower VHS than brachycephalic breeds, which typically have a wide cardiac silhouette and a higher VHS normal range (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 Normal VD (A), right lateral (B), and left lateral projections (C) in an English bulldog. The increased size of the cardiac silhouette relative to the thorax in this patient versus the patient in Figure 1 is evident. VHS, VLAS, M-VLAS, and VRHi collected from the right lateral view are 13.9, 2.4, 2.9, and 4.2, respectively, and 14, 2.2, 2.7, and 4.4, respectively, collected from the left lateral view. Images courtesy of Federico Villaplana Grosso, DACVR, DECVR

Approach to the Cardiac Silhouette

The cardiac silhouette should be evaluated systematically. Using the clockface analogy when evaluating DV or VD projections, the apex of the heart is located at ≈5 o’clock, and the right ventricle is in the region between 5 and 6 o’clock to 9 o’clock, followed by the right atrium, aortic arch, main pulmonary artery (MPA), left auricle, and left ventricle (Figure 4). A similar approach can be followed when evaluating the heart in a lateral projection. The terms cranial and caudal waist or borders are used to describe regions of the cardiac silhouette (Figure 5). Changes within particular regions can indicate which structure is likely abnormal and highlight potential underlying disease processes.

FIGURE 4 Normal VD projection in a large-breed dog showing regions of the cardiac chambers. Orange, navy blue, royal blue, black, white, and gray borders indicate region locations of the right ventricle, right atrium, ascending aorta, MPA, left auricle, and left ventricle, respectively. Abnormalities of the great vessels or auricles would result in focal bulges in their respective regions (not present in this image). The left atrial body (asterisk) can be seen. Illustration courtesy of Jose Narvaez Perez

FIGURE 5 Levophase of a right ventricular outflow tract angiogram in a dog undergoing cardiac intervention. The pulmonary veins, left atrial (asterisk) and ventricular lumens, and ascending and descending intrathoracic aorta can be seen. The cranial and caudal waists (normal in this patient) are highlighted in blue and white, respectively. The great vessels, right atrium, and right auricle are located near the region of the cranial waist, whereas the left atrium and pulmonary veins are located near the region of the caudal waist. The orange and gray lines outline the regions of the right and left ventricles, respectively. An angiographic catheter is in the right ventricular outflow tract, transthoracic pacing patches have been applied, and a transesophageal echocardiography probe is positioned dorsally to the left atrium. Illustration courtesy of Jose Narvaez Perez

Common Acquired Heart Diseases

The most common acquired heart diseases in dogs include myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), both of which primarily affect the left side of the heart. Left-sided cardiomegaly is observed radiographically in dogs with advanced disease and is characterized by an increased apicobasal dimension of the cardiac silhouette and loss of the caudal waist on the lateral projection. In the orthogonal view (specifically the VD view), a focal bulge may be observed at ≈3 o’clock, which is indicative of left auricular dilation. In addition, the borders of the left atrium become more apparent and stretch apart the mainstem bronchi laterally. These findings are proportional to the degree of disease severity (volume overload), and a lack of abnormalities on radiographs do not rule out early DCM or MMVD (Figures 6 and 7). Objective parameters (eg, VHS, vertebral left atrial size (VLAS), modified vertebral left atrial size (M-VLAS), radiographic left atrial dimension) can be used to quantify heart enlargement and predict disease stage in dogs with MMVD and DCM, particularly when echocardiography is not available.4-12 The sensitivity and specificity of these indexes in determining cardiomegaly and disease stage depend on the cutoff used.10-13 For example, VLAS of 2.4 or larger was found to predict left atrial enlargement with 81% sensitivity and 77% specificity in a heterogeneous group (different breeds) of dogs with MMVD5; however, because of the significant variation of normal ranges among breeds, breed-specific reference intervals should be used when available, as 2.4 may fall within the reference interval in some breeds.1-3,14,15

FIGURE 6 Right lateral and DV projections of 2 dogs with significant left-sided volume overload and heart enlargement secondary to MMVD. Moderate (A, B) and severe (C, D) changes can be seen. Dorsal elevation of the caudal portion of the trachea and mainstem bronchi secondary to heart enlargement, soft tissue opacity bulge in the region of the caudal waist representing the enlarged left atrium, and increased apicobasal length of the cardiac silhouette can be appreciated in the lateral views (B, D). Changes in the appearance of the borders of the left atrium and mainstem bronchi, as well as a visible auricular bulge in the DV view can be compared with those from a normal dog (Figures 1-3). An air gun ballistic (A, B) was also found incidentally. VHS, VLAS, M-VLAS, and VRHi collected from lateral view B are 11.4, 2.5, 4, and 3.6, respectively, and 12.7, 3.4, 5.9, and 4.1, respectively, collected from lateral view D.

FIGURE 7 Right lateral (left) and DV (right) projection in a dog with DCM. The apicobasal dimension of the cardiac silhouette is increased, and there is loss of the normal cardiac waist. VHS, VLAS, M-VLAS, and VRHi collected from the right lateral view are 11.2, 2.1, 3.4, and 3.1, respectively. (Note: The DV image is flipped to display the right side of the patient to the left.)

A subset of patients with acquired heart disease may develop left-sided congestive heart failure (CHF). In addition to left-sided cardiomegaly, dogs with active CHF secondary to MMVD commonly exhibit lobar pulmonary venous enlargement on radiographs, as well as an interstitial to alveolar radiographic lung pattern that typically develops in the perihilar region and right caudal lung lobes (Figure 8); however, in dogs with DCM, this lung pattern may be seen in the ventral lung lobes (Figure 9). The radiology lung score is an objective method to quantify severity but was not associated with the recurrence of CHF or survival in one study.16 Dogs administered diuretics may not have pulmonary venous dilation, and some dogs with CHF secondary to acute increase in left atrial pressure (eg, aortic valve endocarditis, chordae tendineae rupture) may not have significant cardiomegaly.

FIGURE 8 DV (left) and left lateral (right) projections consistent with left-sided CHF in a dog with advanced MMVD. Pulmonary venous distention (arrowheads), an interstitial to alveolar pattern in the perihilar region extending caudodorsally, cardiomegaly, and aerophagia are present. VHS, VLAS, M-VLAS, and VRHi collected from the left lateral view are 10.9, 2.8, 4.8, and 3.2, respectively.

FIGURE 9 DV (left) and right lateral (right) projections consistent with left-sided CHF in a dog with advanced DCM. Perihilar to ventral distribution of the severe interstitial to alveolar pulmonary pattern is present in addition to cardiomegaly. VHS, VLAS, M-VLAS, and VRHi collected from the right lateral view are 11.5, 2.1, 4.1, and 3.1, respectively. (Note: The DV image is flipped to display the right side of the patient to the left.)

Common Congenital Heart Disease

Common congenital heart diseases in dogs include pulmonic stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus, and subaortic stenosis. In addition to providing valuable information regarding the pulmonary parenchyma and vasculature, thoracic radiography may provide clues into which type of congenital heart disease is present. For example, a dog with left-sided cardiomegaly and a bulge in the ascending aorta raises suspicion for subaortic stenosis (Figure 10), whereas a dog with right-sided cardiomegaly without an MPA bulge raises suspicion for tricuspid valve dysplasia (Figure 11). Qualitative assessment of individual cardiac chambers with thoracic radiography can be an inaccurate method for diagnosis of congenital heart disease and right-sided heart enlargement in dogs. Definitive diagnosis is achieved with echocardiography.17,18 An objective parameter (ie, vertebral right heart index [VRHi]) could be a useful tool for accurate radiographic determination of right-sided cardiomegaly, although studies are needed to evaluate the influence of left-sided heart enlargement and individual breed differences in the normal range, as well as breed-specific cutoffs used for this parameter (Figure 12).19

FIGURE 10 Left lateral (left) and DV (right) projections of a Jagdterrier with subaortic stenosis. A bulge (arrowheads) secondary to the dilated aortic arch (poststenotic dilation) can be seen. Left ventricular enlargement is also present. VHS, VLAS, M-VLAS, and VRHi collected from the left lateral view are 10.8, 2.1, 2.5, and 3, respectively. (Note: The DV image is flipped to display the right side of the patient to the left.)

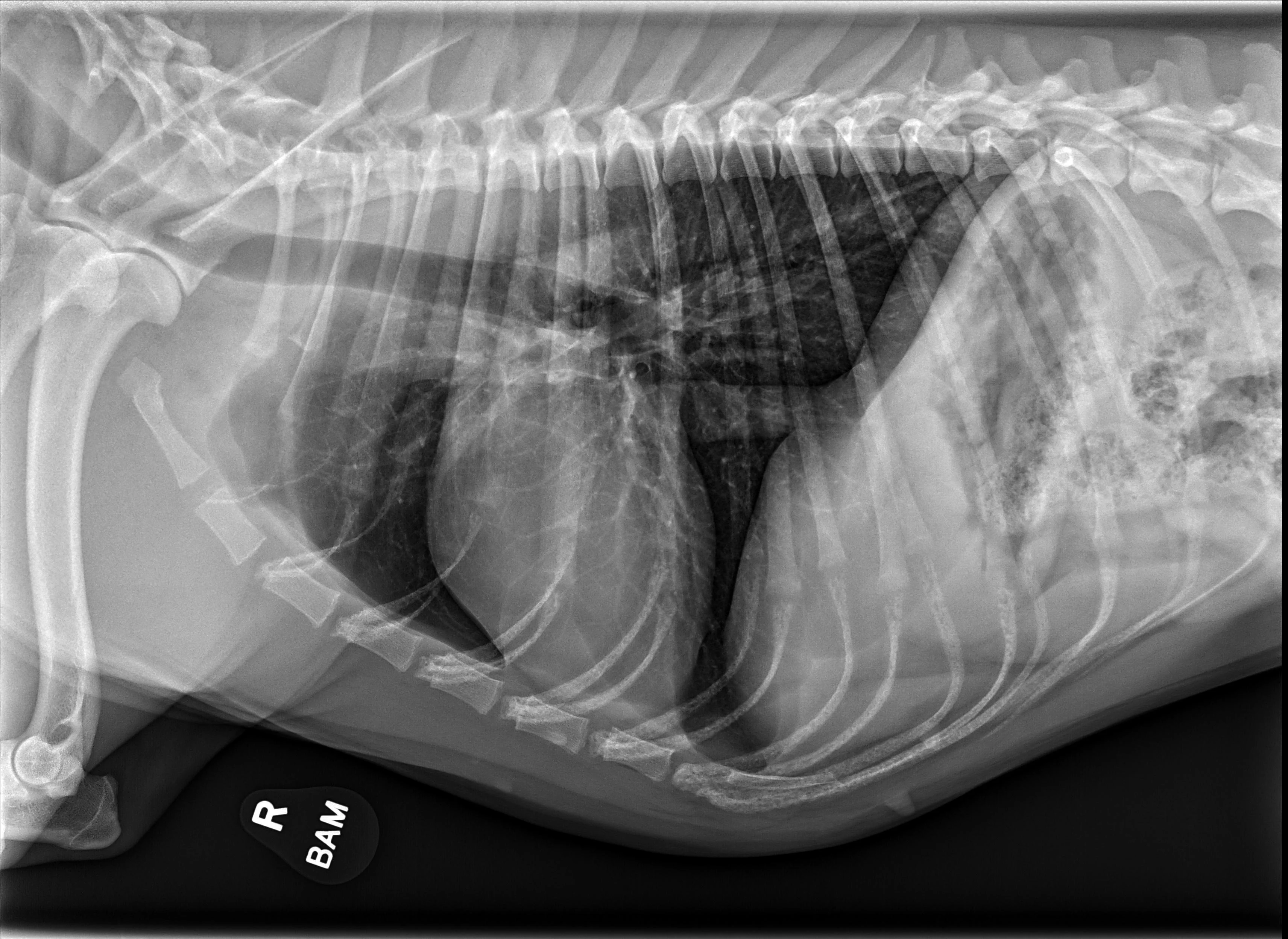

FIGURE 11 Right lateral (left) and VD (right) projections of a crossbreed dog with tricuspid valve dysplasia. The cardiac silhouette has increased width, and the regions of the right atrium and ventricle show roundness. The cardiac apex is displaced to the left secondary to right-sided enlargement (right). The caudal vena cava (arrowheads) is dilated, and there is loss of abdominal serosal detail secondary to increased systemic venous pressures and right-sided CHF, respectively. The pulmonary vasculature is small secondary to pulmonary hypoperfusion (given significant regurgitation across the tricuspid valve and decreased forward blood flow). VHS, VLAS, M-VLAS, and VRHi collected from the right lateral view are 12.3, 2.3, 2.7, and 3.8, respectively. Images courtesy of Bruna Del Nero, DACVIM (Cardiology)

FIGURE 12 Representation of the VRHi with a value of 2.9 in a dog with a normal cardiac silhouette (left), and a dog with pulmonic stenosis and right-side heart enlargement with a VRHi value of 3.6 (right). Using the right lateral projection for measurement, a value ≥3.5 detects right-sided heart enlargement with a sensitivity of 68% and specificity of 86%.16 Images courtesy of Federico Villaplana Grosso, DACVR, DECVR, and Bruna Del Nero, DACVIM (Cardiology). Illustration courtesy of Jose Narvaez Perez

Conclusion

Despite the inherent limitations of evaluating a 3D structure with a 2D imaging modality, thoracic radiography remains a valuable diagnostic tool for dogs with suspected or confirmed cardiovascular disease. Quantitative methods with breed-specific reference intervals provide a practical and effective method to evaluate the cardiac size and predict disease stage in patients with common acquired heart disease when echocardiography is not possible.