In the Literature

Romito G, Gemma N, Dondi F, Mazzoldi C, Fasoli S, Cipone M. Efficacy and safety of antiarrhythmic therapy in dogs with naturally acquired tachyarrhythmias treated with amiodarone or sotalol: a retrospective analysis of 64 cases. J Vet Cardiol. 2024;53:20-35. doi:10.1016/j.jvc.2024.03.002

The Research …

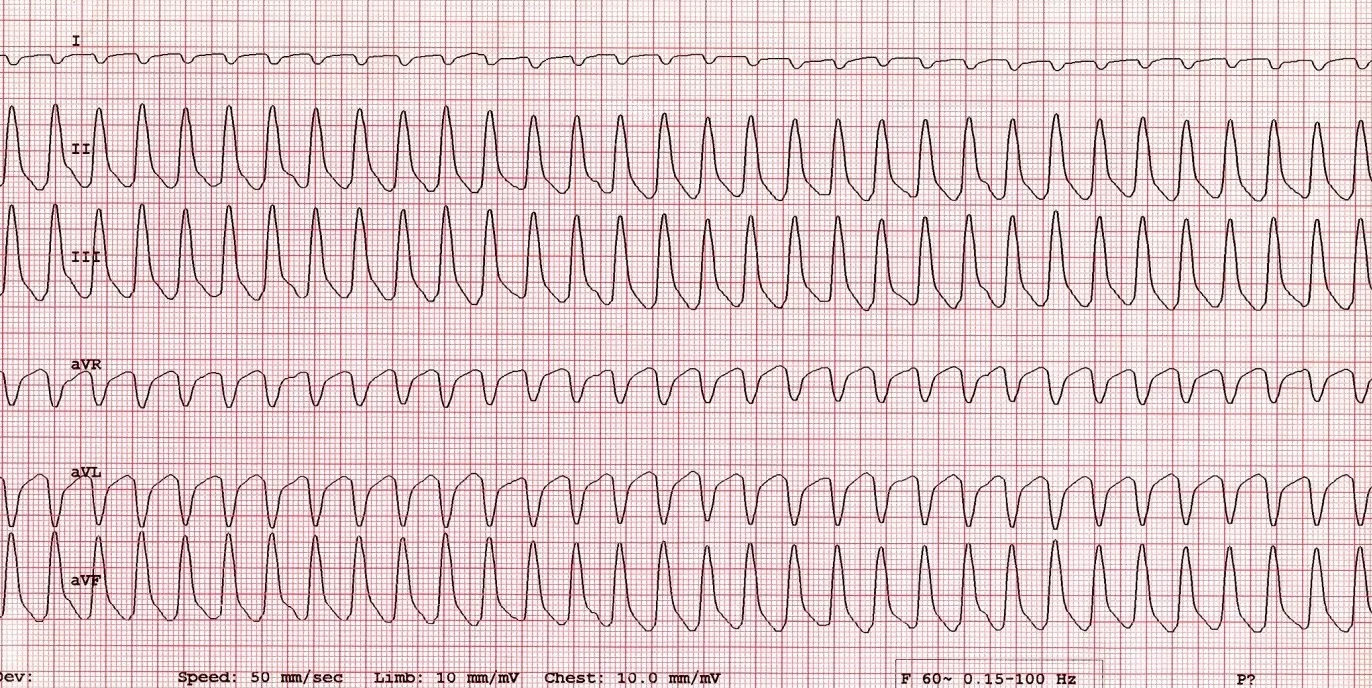

Antiarrhythmic drugs are typically the first-line therapy for supraventricular tachyarrhythmia (SVT) and ventricular tachyarrhythmia (VT) in dogs. Runs of VT are considered a high risk for sudden death.

This retrospective study compared drug efficacy and safety in dogs with VT and/or SVT administered oral amiodarone (n = 24) or sotalol (n = 40). Results of diagnostics, including echocardiogram, ECG, 24-hour Holter recordings, and blood work, were noted on the day of diagnosis and compared with results obtained at a recheck. Drug efficacy for VT was defined as elimination of runs of VT or ≥85% reduction in ventricular premature contractions on a 24-hour Holter recording. SVT therapy was considered successful if cardioversion (ie, restoration of normal sinus rhythm) or a mean heart rate ≤140 bpm on a 24-hour Holter recording was achieved.

Amiodarone was considered effective in 85.7% of dogs with VT, and sotalol was considered effective in 90.9% dogs with VT. Successful treatment of SVT was reported in 75% and 71.4% of dogs treated with amiodarone and sotalol, respectively; however, this finding should be interpreted with caution, as the number of dogs with SVT was too low to draw firm conclusions.

Clinically relevant adverse effects were noted in 8.3% of dogs given amiodarone (GI signs, leukopenia) and 5% of dogs given sotalol (weakness/exercise intolerance, systemic hypotension). Additional effects deemed clinically irrelevant included elevated ALT, elevated AST, and decreased thyroxine with amiodarone and prolonged PQ and QT intervals with sotalol.

… The Takeaways

Key pearls to put into practice:

Although this study was retrospective and some diagnostics were not available for all patients, amiodarone and sotalol appear similarly effective for treatment of VT and/or SVT in dogs. The criteria for drug efficacy may have overestimated clinical benefits, however, as elimination of VT runs only occurred in 76.5% and 93.8% of dogs with Lown-Wolf grade 5 ventricular arrhythmias receiving amiodarone and sotalol, respectively. Of dogs available for long-term follow-up, 33.7% experienced cardiac-related sudden death with a median survival of 183 days.

Significant, persistent risk for sudden death in dogs with ventricular arrhythmias should be discussed with pet owners, regardless of perceived drug effectiveness determined by 24-hour Holter data. History of syncope, heart rate, polymorphism of VT, severity and type of underlying structural heart disease, and patient breed should also be considered.

Twenty-four–hour Holter data provides a limited view of the large daily fluctuation in arrhythmia burden. In humans, longer Holter recordings (7-14 days) to account for daily variability in arrhythmia are more accurate for determining drug efficacy.1 Dogs can easily tolerate 48-hour Holter recordings, which may reveal more meaningful data.

Although treatment-related adverse effects were more frequent in dogs given amiodarone, both drugs were well tolerated overall and considered safe. Owners should be informed of potential adverse effects. In addition to baseline echocardiogram, ECG, and 24-hour Holter recording, blood testing that includes CBC, serum chemistry profile, and a thyroid hormone panel should be performed prior to and 1 to 2 months after initiation of amiodarone therapy, then every 2 to 4 months. If elevated liver enzymes or low thyroxine are present at baseline, sotalol is a safer therapeutic choice. Blood pressure and QT intervals on ECG should be monitored in patients receiving sotalol. Discontinuation or dose reduction of amiodarone or sotalol is recommended in patients with treatment-related adverse effects, which are typically reversible.

You are reading 2-Minute Takeaways, a research summary resource presented by Clinician’s Brief. Clinician’s Brief does not conduct primary research.