Guidelines for Emergency Patient Referral

Katherine Bennett, DVM, DACVAA, Veterinary Specialty Center, Buffalo Grove, Illinois

Christine Egger, DVM, MVSc, CVA, CVH, DACVAA, University of Tennessee

General practitioners generally have a rapport with pet owners and provide important primary care, including preventive medicine, diagnostics, and long-term disease treatment and control, to a variety of patients on a daily basis. However, some patients are presented with or develop conditions beyond the scope of general practice.

In these instances, practitioners may refer patients to other hospitals for more sophisticated diagnostics (eg, MRI), for consultation with a boarded specialist, or for 24-hour observation or intensive nursing care. Referral practices depend on a strong relationship with general practitioners to provide continuity of care and pet owner communication and to promote patient health and safety when a patient is transferred from one practice to another. In human medicine, good communication between the referring physician and the receiving physician, as well as between referring physician and the patient, is essential for a safe referral process and prevents poor continuity of care and delayed diagnoses.1-3 Likewise, in veterinary medicine, good communication between the general practitioner, pet owner, and specialist or referral hospital strengthens the patient care team.

Preparing the Pet Owner for Referral

Strong communication relies on the referring veterinarian as a point of reference for both the referral practice and the pet owner. When a general practitioner recommends referral, he or she should involve the pet owner in the decision: Is the owner willing to seek additional care from another facility? Does the owner have pet insurance, or would additional treatment be cost-prohibitive? Should the facility offer 24-hour care, specialty consultation, diagnostics, or a combination of these? With agreement from the owner, the referring veterinarian should then contact the referral practice to determine their preferences for the referral process.

At this time, the referral practice can ask for patient signalment and history, request the patient’s estimated time of arrival, assess the need for medication (eg, sedation, analgesia) to facilitate transport, and offer a general estimate of initial costs, which may change, depending on additional diagnostic testing after the patient is presented to the referral practice. The referring veterinarian can also inquire whether the referral practice has a transport vehicle for emergency referral cases. The referring veterinarian can use this information to help owners understand the diagnostic services or treatment provided by the referral practice.

Preparing the Patient for Referral

Documentation

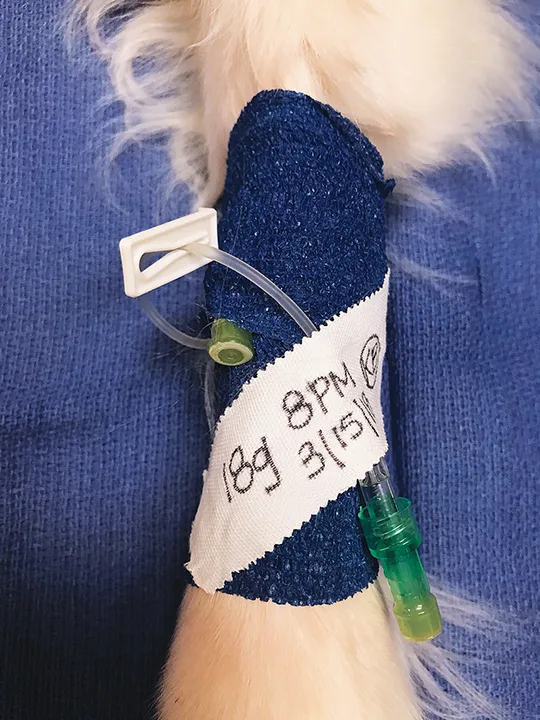

The referring practice should maintain careful records of treatments and diagnostics for continuity of care. If an intravenous catheter or a bandage is placed, the date, time, and signature should be included, along with additional relevant information (Figure).

A study involving the assessment of a referral letter in a human medicine practice noted that in addition to conveying information about the patient, referral letters also reflect the diagnostic skills, communication skills, and professionalism of the doctor.3 Documentation should be succinct and detailed. Descriptors of the patient, presentation, physical examination findings, treatments, and diagnostics should be included, as should the date and time, doses, and routes of medications and fluids, when possible. In addition, physical and/or electronic copies of diagnostics (eg, imaging, blood work) should be included.

Intravenous catheter placement with informative labeling, including catheter size, date and time placed, and the veterinary team member’s initials

Medication

After the initial examination is performed by the referring veterinarian, sedation and analgesia are crucial to facilitate comfortable transport of the critical patient. The transportation time between practices will likely determine the dose and route of sedative/analgesic that is administered. Communication with the referral veterinarian should help facilitate an analgesic choice that will keep the patient comfortable without causing hemodynamic or neurologic instability before arrival at the referral practice. Drugs to consider include those that are reversible and those that will last the duration of transportation; when applicable, long-lasting antiepileptics (eg, levetiracetam, phenobarbital) and analgesics (eg, pure μ-opioid agonists) should be considered.

Every medication administered to a patient, particularly for transportation, requires a prescription and associated prescription label. This allows the pet owner to be in possession of the medication (especially controlled substances) while transporting the patient. Depending on local state laws, many hospitals will not receive controlled substances, and prescribed medication for critical patients may not be used at the referral hospital.4

Transport

Transport of a critical patient can be difficult, especially when performed by the pet owner. Patients should be stabilized before transport, although the nature of the emergency may preclude complete stabilization. Large, open wounds should be carefully bandaged before transport. Stabilizing patients with possible fractures is ideal but may require instruction from the receiving surgeon, further promoting the importance of communication. Some larger referral hospitals may provide an ambulance service to facilitate critical patient transport. Some ambulance services may provide oxygen administration, patient monitoring, intravenous fluid administration, and safe patient restraint for transport in addition to patient transport.5

Using appropriate protective tools for transport (ie, those that do not prevent the patient from breathing, panting, or vomiting) such as Elizabethan collars or basket muzzles can help ensure pet owner and veterinary team safety.

Maintaining patient comfort in the vehicle is essential. Patients should be placed safely in the vehicle with support for their head and neck and any other wounds or fractures. Vehicle temperature is also critical, as patients in shock can be highly susceptible to extreme heat and cold. Respiratory distress can be worsened by heat, so cool air in the vehicle is helpful to promote anxiolysis.

TOP 5 ITEMS TO COMMUNICATE WHEN REFERRING CRITICAL PATIENTS

Patient signalment, presenting complaint, and relevant history

Initial physical examination findings

Treatments, such as intravenous catheter placement and fluids and medications given (including times, routes, and dosages)

Diagnostics (eg, radiographs, FAST examination, blood work)

Current patient status (eg, “stable,” “experiencing respiratory difficulty”)

Conclusion

Follow-up communication between the referring veterinarian and the referral practice is paramount to providing both continuity of care and treatment follow-through. Updates on diagnostics, findings, treatments, and patient outcome are all critical for both practices to be aware of the case progression and to facilitate an understanding of the case if the patient is returned to the referring veterinarian for additional care.