Giardiasis in Dogs & Cats: An Overview

Valeria Scorza, MV, MS, PhD, Colorado State University

Giardiasis is a protozoal infection that can affect a wide variety of vertebrates, including cats, dogs, and humans.

Profile

Definition

Based on genetic studies, Giardia duodenalis is a species complex composed of 8 assemblages (A–H).

Some assemblages are host specific, but others can be harbored by several species and may be considered potentially zoonotic.1

Dogs are most commonly infected by host-specific assemblages C and D, while cats harbor host-specific assemblage F.

Cats and dogs also harbor zoonotic assemblages A-I, A-II, A-III, A-IV, and B.2

Systems

The infection can be asymptomatic or produce GI signs (ie, diarrhea, malabsorption, weight loss).

Prevalence

Prevalence is 5% in healthy cats and dogs, and 15% in clinically ill animals.3

Prevalence is greater in young cats and dogs than in mature ones.

Geographic Distribution

Giardiasis is diagnosed worldwide.

Signalment

Giardiasis can occur in humans, domestic animals, livestock, and wild animals.

There is no breed or sex predilection.

Causes

Transmission occurs via the fecal–oral route by direct or indirect ingestion of contaminated water, food, or fomites.

Infection with Giardia spp occurs in 2 stages: the trophozoite and the cyst.

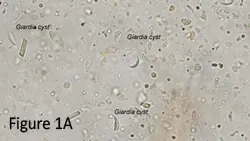

The cyst (See Figure 1, Giardia cysts seen on (1A) fecal flotation at 100× magnification and (1B) immunofluorescent antibody assay at 400× magnification) is responsible for transmission and can survive several months outside the host in wet, cold conditions; it can dehydrate in dry and hot conditions.

The prepatent period ranges from 5 days–16 days in cats and 5 days–12 days in dogs.

Peak periods of cyst shedding can occur on days 2–7.

Risk Factors

Immunosuppressed animals and animals living in crowded environments are at highest risk for exhibiting GI disease.3

Younger animals are more likely to show clinical signs.3

Pathogenesis

The mechanism of infection can involve:

Production of toxins

Disruption of normal flora

Induction of inflammatory bowel disease

Inhibition of normal enterocyte enzymatic function

Blunting of microvilli

Induction of motility disorders

Induction of intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis4

As a result, diarrhea can be caused by a combination of intestinal malabsorption and hypersecretion of electrolytes.

Signs

Most dogs and cats that shed Giardia organisms are asymptomatic.

In clinically affected animals, diarrhea can be mucoid, pale, and soft and have a strong odor; steatorrhea may be present.

Mild to moderate discomfort from abdominal inflammation can occur with diarrhea.

Immunosuppressive disease or co-infection with other pathogens can exacerbate clinical signs.5

Whether different assemblages cause different signs remains unknown.

Diagnosis

Definitive

In cats and dogs with diarrhea, the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) guidelines recommend testing by direct smear, fecal flotation with centrifugation, and a specific fecal ELISA.

Related Article:Fecal Examination Techniques

Direct Smear

Trophozoites are rarely seen in solid feces but can be observed in a small sample of fresh diarrhea when mixed with a drop of 0.9% saline solution on a microscope with a coverslip.

At 100× magnification, active falling leaf motion of trophozoites can be observed.

Trophozoites can appear very active within a small area of the slide and can be easily kept in the field of view.

At 400× magnification, structural characteristics can be observed.

Fecal Flotation with Centrifugation

If Giardia trophozoites are not detected in direct smears, cysts should be examined by fecal flotation using Sheather sugar (1.25 SG) and zinc sulfate (1.18 SG).

Zinc sulfate is considered the flotation medium of choice for Giardia cyst detection.

Fecal ELISA

SNAP Giardia Test (idexx.com) is the only commercially available ELISA for detecting Giardia spp in cats and dogs.

Some laboratories use ELISA plate assays that have been internally validated to detect Giardia spp in cats and dogs.

To rule out Giardia infection, ≥3 samples should be examined within 1 week.

Related Article: Idexx Snap: Giardia for Dogs & Cats

Differential

In dogs and cats, noninfectious and other infectious causes of small intestinal diarrhea, IBD, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, malabsorption syndromes, and neoplastic intestinal disease need to be ruled out.6

In cats, Tritrichomonas foetus infection must be ruled out.

Laboratory Findings

In general, results of CBC, serum biochemistry panel, and urinalysis will be within reference ranges.

Any detected abnormalities are likely from dehydration and electrolyte losses associated with diarrhea.

Other Diagnostics

Immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) assay can detect Cryptosporidium spp.

IFA assay is more sensitive than fecal flotation (compared with that of performing single fecal ELISA).

A fluorescence microscope is needed to read the slide.

PCR testing currently is only indicated for determining G duodenalis assemblages.

Multilocus (amplification of more than 1 gene) analysis has been recommended.7

Postmortem

Giardiasis is nonfatal.

In experimentally infected gerbils, histopathologic findings include reduced jejunal villus height and increased jejunal crypt depth.

Slight to moderate infiltration of inflammatory cells was noted in the lamina propria and was typically more severe in the duodenum.

Inflammatory cells included plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and mast cells.

Treatment

Inpatient or Outpatient

In general, cats and dogs infected with Giardia are treated as outpatients.

If marked diarrhea occurs and fluid therapy is indicated, animals may require hospitalization.

If vomiting and small bowel diarrhea are primary clinical signs, highly digestible bland diets are indicated.

If large bowel diarrhea is principal clinical sign, high-fiber diets should be used.

Primary focus of treatment is resolution of diarrhea.

Treatment of asymptomatic dogs that shed Giardia cysts and of cats in general has been controversial.

Client Education

Because healthy pets are not considered significant health risks for humans, elimination of infection is secondary.

CAPC guidelines suggest that asymptomatic dogs and cats may not need treatment.

Contraindications, Precautions, & Interactions

GI and neurologic toxicity after chronic therapy or acute high doses of metronidazole has been reported in some dogs and kittens.9,12

Metronidazole USP induces salivation and inappetence in some cats, but metronidazole benzoate is well tolerated.

Neurotoxicity has been observed after administration of ronidazole.

Albendazole can cause bone marrow suppression in cats and is not currently prescribed for use in cats or dogs.13

Paromomycin can cause deafness and renal failure in some cats.9

Medications

Drugs/Fluids

No drugs are approved in the United States for treatment of giardiasis in cats and dogs, but several drugs are commonly used (See Table in PDF).

In Florida, cats and dogs with acute giardiasis must be reported to the state department of health.8

Metronidazole (USP or benzoate) may be indicated if clinical findings suggest concurrent Clostridium perfringens overgrowth.

Ipronidazole has been shown effective for treatment of giardiasis in 2 dogs.9

Six dogs treated with ronidazole and bathed twice with a chlorhexidine shampoo, along with disinfection of enclosures with 4-chlorine-M-cresol, became negative for Giardia cysts and antigen within 26 days.10

Fenbendazole can be used, particularly when concurrent infection with cestodes or nematodes is suspected.

When fenbendazole was used for treatment of cats concurrently infected with Giardia and Cryptosporidium parvum, only 4 of 8 cats stopped shedding Giardia cysts.11

Combination of febantel, pyrantel, and praziquantel using different protocols was generally successful when treating giardiasis in dogs and cats.8,9

Follow-up

Patient Monitoring

Fecal flotation can be used to evaluate treatment success.

In persistent infections, combination therapy with a second drug from an alternate class is indicated (eg, fenbendazole plus metronidazole).

At Colorado State University laboratory, paromomycin or nitazoxanide was used in some cats and dogs with resistant giardiasis, but data were not controlled.14

Azithromycin has been used successfully in dogs with resistant giardiasis, but additional studies are needed.15

Prevention

Environmental disinfection is recommended.

Feces should be removed daily and contaminated surfaces disinfected by steam cleaning or use of quaternary ammonium compounds (1-minute contact time).

Infected animals should be bathed with shampoos to remove fecal debris and cysts.

Complications

In animals with persistent diarrhea from Giardia infection, underlying disorders should be considered:11,14

Inflammatory bowel disease

Bacterial overgrowth

Coinfection with other organisms (ie, Cryptosporidium spp, T foetus)

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

Immunodeficiency

In General

Relative Cost

Treatment and follow-up care for uncomplicated cases of diarrhea: $

Diagnostic workup for chronic cases of diarrhea and presence of Giardia cysts in fecal flotation: $$–$$$

Prognosis

In most cases, diarrhea will resolve after treatment.

Future Considerations

The role that cats and dogs play in the transmission of giardiasis to humans should be investigated further.

Public Health Considerations

Most cats and dogs harbor species-specific assemblages of G duodenalis and are not considered a significant human health risk, although the presence of zoonotic assemblages in dogs, cats, and humans in the same household has been described.1,16

Healthy cats and dogs should be screened for infection every 6–12 months.

It has been suggested that if Giardia cysts are detected in an asymptomatic animal, the animal should not be treated.