History & Signalment

Bailey, an 8-year-old, 20-lb (9-kg) neutered male bichon frise crossbreed, was presented for a 3-day history of lethargy, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and progressively decreasing appetite.

Physical Examination

On physical examination, Bailey was quiet, alert, and responsive. BCS was 6/9. Vital parameters were within normal limits. Bailey was tense and exhibited diffuse pain on abdominal palpation. Thoracic auscultation was within normal limits.

Diagnostics

Initial differential diagnoses included pancreatitis, foreign body ingestion, gastroenteritis, and peritonitis.

CBC results indicated an acute inflammatory leukogram characterized by a leukocytosis with a neutrophilia, left shift, lymphopenia, and monocytosis (Table 1).

Table 1: CBC Abnormalitiesa

a Values not shown were within the reference interval.

Serum chemistry profile results showed increased ALP, mild hypoproteinemia due to a mild hypoalbuminemia likely secondary to inflammation (albumin is a negative acute-phase protein) and/or due to third-space loss in the peritoneal cavity, and borderline hypokalemia (Table 2).

Table 2: Serum Chemistry Profile Abnormalitiesa

a Values not shown were within the reference interval.

Abdominal radiographs showed no abnormalities, and no foreign material was visualized within the GI tract. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a moderate amount of peritoneal fluid; the gallbladder appeared enlarged and contained centrally located echogenic material with multiple echogenic striations that extended to the gallbladder wall. The mesentery appeared diffusely hyperechoic, consistent with peritonitis.

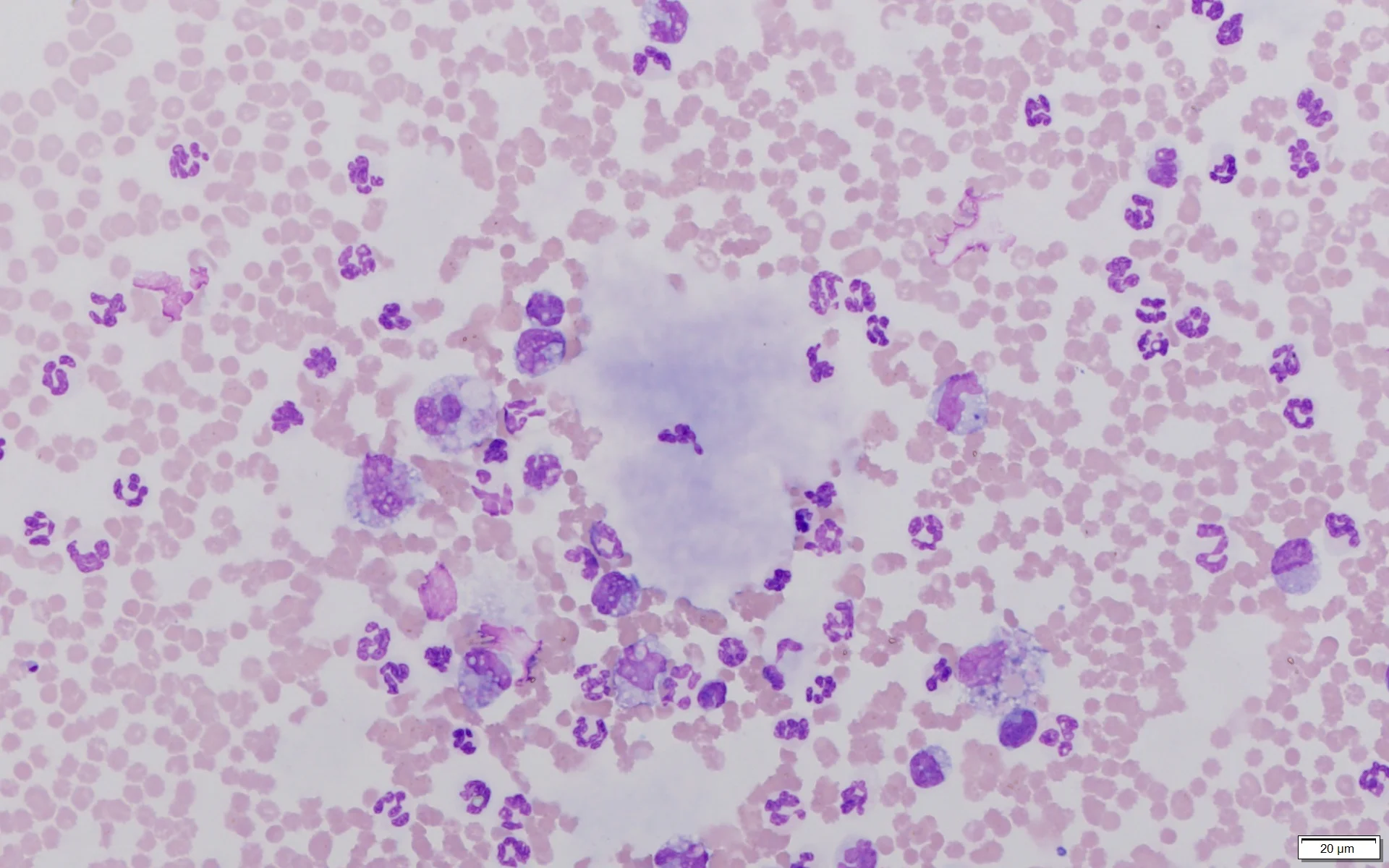

Ultrasound-guided abdominocentesis was performed. Analysis of the peritoneal fluid showed a total protein concentration of 3.9 g/dL, a hematocrit of 6%, and a total nucleated cell concentration of 67,600/μL. Cytologic examination of the peritoneal fluid (Figures 1 and 2) revealed the nucleated cell differential as ≈65% neutrophils, 30% macrophages, and 5% reactive mesothelial cells. A significant amount of amorphous, pale, basophilic material (ie, white bile) was present in the background and within macrophages.

Direct smear of peritoneal fluid. Multiple lakes of amorphous, pale, basophilic material (solid arrows) consistent with white bile can be seen along with abundant RBCs (circle), neutrophils (curved arrows), numerous macrophages (arrowheads), and occasional reactive mesothelial cells (square). Modified Wright’s stain, 200× magnification

Direct smear of peritoneal fluid. Lake of amorphous, pale, basophilic material (solid arrow) consistent with white bile can be seen along with abundant RBCs (circle), neutrophils (curved arrows), and numerous macrophages (arrowheads) that sometimes exhibit erythrophagocytosis. Modified Wright’s stain, 600× magnification

Results were suggestive of a bilious effusion (ie, bile peritonitis) secondary to rupture of a gallbladder mucocele. Bailey was scheduled for an immediate exploratory laparotomy. Midazolam (0.2 mg/kg IV), morphine (0.4 mg/kg IV), and ketamine (7 mg/kg IV) were administered. Bailey was maintained on isoflurane. A ruptured gallbladder mucocele was confirmed on laparotomy. Gelatinous bile was seen throughout the abdominal cavity, and diffuse peritonitis was present.

Diagnosis: Ruptured Gallbladder Mucocele & White Bile Peritonitis

Treatment

During the laparotomy, the gallbladder was localized, and several stay sutures were placed. Patency of the common bile duct was evaluated using an 8-French rubber catheter threaded normograde through the opening of the cystic duct of the ruptured gallbladder and passed through the common bile duct. The duct was flushed and the catheter removed. Two circumferential ligatures and 2 hemaclips were placed around the neck of the gallbladder, which was transected, removed, and submitted for histopathologic examination. The abdomen was flushed with sterile saline multiple times and inspected for bile remnants that were then removed. The linea alba was closed with a simple continuous suture pattern, and a 2-layer closure of subcutaneous tissue was performed.

Following surgery, lactated Ringer’s solution (LRS) with 16 mEq of potassium chloride per liter of LRS, at 1.5 times the maintenance dose, fentanyl CRI (5 micrograms/kg/hour), famotidine (1 mg/kg slow IV every 12 hours), hetastarch (20 mL/kg/day), and ampicillin/sulbactam (22 mg/kg IV every 8 hours) were administered.

One day after surgery, the fluid rate was decreased to a maintenance dose, and fentanyl CRI was decreased to 4 micrograms/kg/hour, then to 3 micrograms/kg/hour. Over the next 3 days, Bailey continued to improve and started to develop interest in food after mirtazapine (7.5 mg/dog PO every 24 hours) was administered. IV medications were discontinued and replaced with tramadol (8 mg/kg PO every 8 hours for 7 days), amoxicillin/clavulanate (20 mg/kg PO every 12 hours for 28 days), and ursodiol (12.5 mg/kg PO every 24 hours), and Bailey was discharged.

Treatment at a Glance

Immediate surgical intervention is indicated in patients with gallbladder mucocele rupture and secondary peritonitis.3

Medical management (eg, ursodiol) is less favorable but may be a viable secondary option when surgery cannot be pursued and gallbladder rupture is not present.3

Outcome

At the 2-week postoperative examination, Bailey was healing as expected, appeared bright and alert, and was noted to have a gradually improving appetite. Blood work results were within normal limits.

Related article: Top 5 Canine Biliary Diseases

Discussion

A gallbladder mucocele is a mucinous cystic hyperplasia of gallbladder and biliary epithelium. Mucoceles are believed to occur secondary to inflammation and cholelithiasis; however, a specific underlying cause has not been determined.1 Dysfunction of mucus-secreting cells within the gallbladder mucosa can lead to accumulation of mucinous material and subsequent extrahepatic biliary obstruction and cholestasis.1,2

Gallbladder mucoceles predominantly affect senior dogs. Any breed can develop a gallbladder mucocele, but Shetland sheepdogs, miniature schnauzers, cocker spaniels, and bichon frises are overrepresented.3,4 Patients with a gallbladder mucocele are typically presented with acute clinical signs associated with extrahepatic biliary obstruction or rupture of the gallbladder, including lethargy, vomiting, jaundice, abdominal pain, diarrhea, polyuria, or polydipsia.3

Abdominal ultrasonography is the most common tool for diagnosing gallbladder mucoceles, which may be found incidentally if rupture has not occurred.3 If gallbladder rupture and peritoneal effusion are present, fluid analysis with cytologic examination and determination of fluid bile acid concentrations may aid in definitive diagnosis. The most prominent cytologic finding is acellular, blue, mucinous material seen within macrophages and in clumps and lakes throughout the background.1,2 The term white bile, first used in the human literature, has been used to describe mucinous material; however, this material does not contain bile constituents (eg, bilirubin).1,2 Numerous inflammatory cells (predominantly neutrophils) are also typically seen.1

Gallbladder mucoceles indicate immediate surgical intervention, especially with gallbladder rupture and associated peritonitis, as patients with these concerns at the time of surgery have a less favorable prognosis than dogs without gallbladder rupture and peritonitis.5

Cholecystectomy is considered the standard treatment for gallbladder mucoceles and has been shown to result in the best likelihood of long-term survival. Medical management (eg, ursodiol) can be pursued as an alternative if surgery is not an option and rupture is not present; however, medical management is associated with shorter survival time than surgical treatment.3

Take-Home Messages

Abdominal ultrasonography and cytology can help initially diagnose a gallbladder mucocele with gallbladder rupture.3

A ruptured gallbladder mucocele should be considered the top differential diagnosis in patients with peritoneal effusion that contains inflammatory cells and acellular, amorphous, blue, mucinous material when stained with a Romanowsky-type stain (eg, 3-step quick stain, modified Wright’s stain).1,2

Gallbladder mucoceles appear to develop secondary to cholelithiasis or inflammation within the gallbladder.2

Gallbladder mucoceles can lead to weakness of the gallbladder wall and subsequent rupture, increasing the likelihood of acute peritonitis.3

Certain breeds are more predisposed to gallbladder mucocele formation, including Shetland sheepdogs, miniature schnauzers, cocker spaniels, and bichon frises.3,4

Early surgical treatment is important in improving patient outcomes.3,5