Fungal Cultures for Diagnosing Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytosis is the most common infectious and contagious skin disease of dogs and cats. Its 3 pathogens of importance are Microsporum canis, M gypseum, and Trichophyton species. Dermatophytosis has some classic clinical presentations, but the disease is pleomorphic. A fungal culture is a reasonable core diagnostic test in any animal presenting with hair loss and/or follicular skin disease.

Dermatophytosis is highly contagious and easily transmitted, and in the author's practice is seen increasingly in dogs that go to dog parks or "doggy day care," in animals being boarded, and those from shelters or rescue organizations. With respect to the latter, a fungal culture is as important as screening new arrivals for infectious viral or parasitic diseases.

Related Article: Using a Wood’s Lamp

What You Will Need

Individually wrapped toothbrushes

Sterile forceps

Alcohol wipes

Sterile cotton-tipped swabs

Fungal culture medium

Acetate tape (clear or frosted)

Glass coverslips

Lactophenol cotton blue or new methylene blue stain

Markers

Plastic self-closing sandwich-size bags

Clear plastic storage box

Inexpensive digital fish tank thermometer

STEP BY STEP FUNGAL CULTURES

Step 1. Culture AreaDesignate a site for in-house fungal cultures. Cultures must be examined daily, so the site should be near the clinic's main laboratory. It is strongly recommended that culture plates be kept in plastic containers. Inexpensive shoe-box-size storage containers are ideal because they are small enough to fit in most laboratories and can be disinfected regularly. Keeping cultures in a single site minimizes the possibility that they will get lost or not be examined and the plates can be checked daily. Also, the temperature inside the boxes will be warmer than the ambient room temperature, helping incubate the plates.

Step 2. Preventing Incubation ProblemsSeveral problems are commonly encountered with in-house incubation of fungal cultures. These include dehydration of plates; too cold an ambient temperature, which results in poor sporulation; and

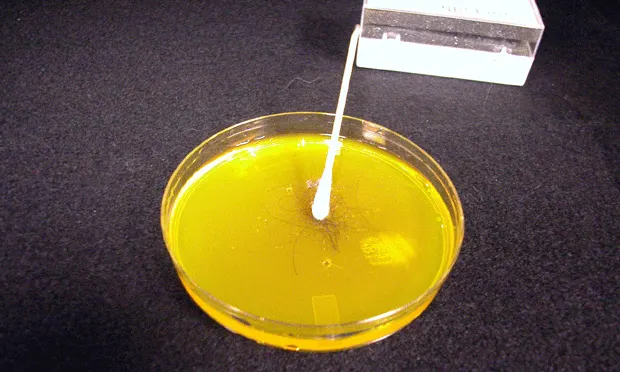

contamination of plates with media mites. Problems with dehydration can be minimized by keeping plates in an airtight container (A). Placing individual plates in a self-sealing sandwich bag can help solve this common problem and also prevent and/or contain media mite infestations. Media mites are microscopic mites associated with food or free-living in the environment. Possible sources of contamination include the animal itself, food sources in the clinic, and environmental debris. The source is often not identified. In the author's laboratory, media mite infestations are commonly associated with cultures from outdoor animals or large animals. One telltale sign is a serpiginous line of red on the fungal culture medium (B).

It is widely recommended that cultures be incubated at "room temperature," but room temperature varies among clinics and seasonally. Ideally, incubation temperature should remain at 75ºF to 80ºF. A small, inexpensive digital fish tank thermometer is a good tool for monitoring the temperature (C). In my own laboratory, the thermometer is left in its original packaging for easy cleaning, but another option is to keep the thermometer in a plastic bag to prevent contamination.

Step 3. Medium SelectionMany commercial culture media are available for use in veterinary practice. In my opinion, the criteria for selection should be: getting the most volume for the money; the ease in which plates can be inoculated and sampled; whether plates have a red color indicator; and shelf life. In general practice, I recommend the use of dermatophyte test medium (DTM). A glass jar can be used with this medium if the jar's opening allows for insertion of a toothbrush for inoculation and easy sampling. Jars can be problematic, however, because closing them too tightly often leads to an overgrowth of bacteria or yeast. Plates with small surfaces should be avoided because they make recognizing suspect colonies more difficult-the entire surface of the plate will often turn red very rapidly, making it hard to monitor colonies. Note that plates that require refrigeration are at risk of being ruined if they are accidentally frozen; store the plates on the refrigerator door or in the vegetable crisper.

Step 4. Inoculation OptionsThere are 2 methods for sampling lesions or animals for dermatophytosis. One is to pluck individual hairs and the other is to use a toothbrush or equivalent for sampling the entire body or a site. Individual hair sampling is best suited for Wood's-lamp-positive hairs or hairs that are grossly abnormal. If the area is heavily contaminated, wiping it with alcohol may decrease contaminant growth. Individually wrapped toothbrushes, which are mycologically sterile, can be purchased in bulk at dollar discount stores or from hotel supply companies. Alternatively, sterile gauze sponges with a tight weave can be used.

Plucking individual hairs: Grasp the hair in the direction of growth and tug gently, trying to get the root bulb. Gently press the hair onto the growth medium.

Toothbrush or gauze sponge sampling: This technique can be used to sample a large lesion or the entire body of an animal. Comb or wipe the coat aggressively until hair is clearly visible on the surface or in the bristles. Be sure to sample near the eyes, in the ears, and between the toes. When inoculating a plate with a toothbrush or gauze, gently stab the bristles or press the gauze over the entire surface of the plate. Be careful not to press too hard or the medium will be pulled off by the toothbrush. If the hair coat is visibly contaminated with debris, wipe it with a cloth to minimize contaminant growth swarming the culture plate.

Caution: When using a whole-body sampling technique, always sample suspect lesional areas last to avoid mechanical spread of infectious material.

Step 5. Monitoring Growth & IncubationPlates should be checked daily for fungal culture growth. A good practice is to designate a technician to check cultures daily and keep a log of color change and growth on the plates. When using DTM, look for white or buff-colored colonies (A) that develop a red color change around them as they grow. This is a key characteristic of pathogens. Fungal culture colonies

that are grossly or microscopically pigmented (as are the brown areas in A) are not pathogens, they are contaminants. All pale or buff-colored colonies should be microscopically examined. Cultures from animals that live outdoors or in heavily contaminated environments may be rapidly overgrown with contaminants, masking or making it difficult to identify a pathogen. Close inspection of this plate (B) revealed M canis was present, but as the colonies were swarmed by contaminants, this finding could easily have been missed. New cultures should be performed in such cases.

Note: that while most pathogens will grow and sporulate within 7 to 10 days, Trichophyton cultures often take up to 14 days. Plates should be kept for at least 14 days and preferably for 21 days.

In my experience, fungal culture growth in animals undergoing treatment can be delayed, often developing during week 3 of incubation. In addition, colonies may look grossly atypical. The colonies will still be pale, but sporulation may be significantly delayed. The plate pictured (C) is from a cat receiving topical therapy. Note the ring of white colony growth on the margins of the plate. Microscopically, these were identified as M canis colonies, which did not grow until more than 15 days after inoculation.

PROCEDURE PEARL: Fungal culture plates are easier to inoculate if they are allowed to warm up to room temperature beforehand.

PROCEDURE PEARL: When inoculating a plate with a toothbrush, be careful not to press too hard or the medium will be pulled off by the toothbrush.

Step 6. Sampling for Microscopic IdentificationThe most common pathogen encountered in private practice is Microsporum, and this genus is relatively easy to identify microscopically.

Trichophyton species can be more difficult to determine. A valuable resource to aid in identification is www.doctorfungus.org.

Acetate tape is most commonly used to collect samples (A). Either clear or frosted tape can be used, but the latter requires more manual dexterity. The key to good visibility is sandwiching the sample between 2 drops of stain. Place a drop of stain on a slide and press the sticky side of the tape to the edge of the colony. If clear acetate tape is used, the tape is placed sticky-side down over a drop of stain, another drop of stain is added to the nonsticky side, and then the glass coverslip is placed. If frosted tape is used, the tape is placed sticky-side up, a drop of stain is added on top of the tape, and the glass coverslip is added (B). The coverslip can be placed directly over the tape. These upside-down preparations with frosted tape work as well as those with clear tape. To prevent the tape from adhering to the microscope, the entire surface of the tape should be coverslipped. Lactophenol cotton blue stain is recommended because the phenol will kill the spores; however, new methylene blue stain can also be used.

When it is not possible to sample the plate with acetate tape, a small sample of the colony will need to be collected using a sterile inoculating loop, small forceps, or even a stick. The sample is transferred to a glass slide where a drop of stain has been placed (C, D).

PROCEDURE PEARL: Allowing stained samples to sit for 5 to 10 minutes before examining them allows for intracellular accumulation of stain and easier identification.

Step 7. Microscope TechniqueI examine all slides at low power in order to find areas where the hyphae have stained well; then move to a higher power for final examination. M gypseum produces large numbers of macroconidia (A). M canis produces fewer macroconidia (B), and the walls are thicker and rough.

If the laboratory temperature is too cold, M canis may not sporulate and all that will be seen are hyphae with thick, finger-like projections on the ends (C). This is evidence that the colony is trying to sporulate. Increasing the temperature in the laboratory will help speed the process.