Fractured Upper Canine Tooth

An 8-year-old, spayed, female Rottweiler mix was presented for an acute episode of pruritus accompanied by a swollen muzzle. The owner thought the swelling was caused by allergies, but it was actually caused by a fractured upper canine tooth.

History. The patient had a long history of pruritus. The owner believed that the antihistamines the dog was being given for allergies were no longer effective, accounting for both the itch and swelling.

Examination. The physical examination confirmed pruritus and that the left side of the muzzle was swollen. Oral examination revealed fracture of the upper-left canine tooth and a fistula on the distal aspect of the tooth at the mucogingival junction. The owner was not aware of the fractured tooth, which appeared to be long-standing. The dog had had dental prophylaxis several times.

Ask yourself ...

Which of the following is the optimal long-term therapy for this patient?A. Give an injection of long-acting steroids and hope that the tooth falls out and the dog stops itching.B. Give an injection of penicillin/ dexamethasone and hope that the owner moves out of state.C. Place the patient on steroids and pulse antibiotic therapy once a month on a long-term basis to control the abscessed tooth and pruritus. Ignore the signs of Cushing's disease.D. Dispense antihistamine, short-acting steroids, and antibiotics.E. Dispense antihistamine, short-acting steroids, and antibiotics, adding pain medication. Perform laboratory analysis, and schedule patient for dental examination, dental radiographs, and possible root canal or surgical extraction.

Correct Answer: E

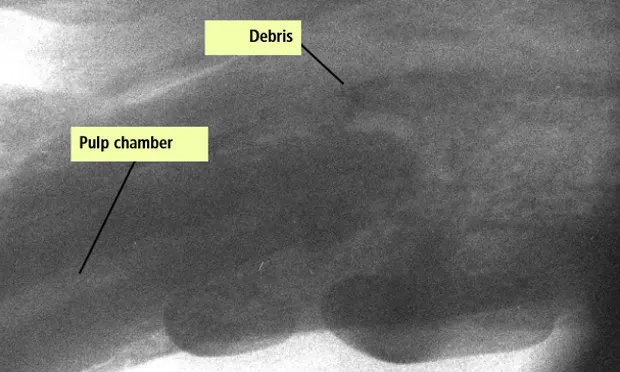

Fractured abscessed teeth commonly go undiagnosed. The pulp chamber and tooth crown may not be obvious to the naked eye. However, to bacteria they look like the Holland Tunnel-that is, huge, dark, and in this case loaded with nutrition.

The pathology of a fractured tooth is relatively simple. A sterile environment becomes open to hoards of bacteria that hide from view. Pupal necrosis and abscesses through the root tip and bone may take months to years to develop, and it is these events that cause the owner to bring the pet to the veterinarian.

Initial management includes the correct diagnosis. The lesion appears as a tiny, dark spot that can be entered with a dental explorer. This spot is commonly assumed to be normal tertiary dentin in the tooth of an older dog. The presence of: 1) an irregular slab fracture of the tooth surface that-as in this case-is not a smooth "wear facet" like those resulting from playing with a tennis ball, 2) the draining fistula, and 3) the swollen muzzle point to a periapical abscess. Dental radiography confirms the diagnosis.

Management could include medication for the acute pruritus and bacterial infection of the periapical abscess (choice D). However, this choice is not the complete treatment because pain management is not addressed. Even though the abscess and pruritus will probably resolve temporarily, neither has been appropriately treated on a long-term basis. Choices A, B, C, and D are therefore not acceptable, although they are used.

Fractured abscessed teeth can be treated in three ways: surgical extraction, conventional endodontic therapy, or surgical endodontic therapy. Client communication and compliance with revisits for dental radiography and possible failure of surgical endodontic therapy played a significant role in treatment.

This client wanted the least chance of complications. Also, the patient would have been a poor candidate for conventional endodontic therapy because the entire palatal apex of the tooth was resorbed. The tooth would have required surgical endodontics for any chance of success. Endodontics requires a mucosal flap, cortical buccal bone removal, and removal of the diseased portion of the apex (which was quite a large area in this case). Furthermore, surgical endodontics-as well as surgical extraction-requires antibiotics and pain medication. So in this case, the ideal choice was surgical extraction.

The tooth was immobile. Extraction of an immobile tooth without a mucosal flap; cortical buccal bone removal; and firm, controlled elevation can be extremely traumatic and unnecessarily lengthy for both the patient and the operator. However, with a high-speed handpiece (400,000 rpm), air-driven dental equipment, sharpened dental elevators, and proper technique, the tooth can be removed atraumatically in as little as 5 minutes. After extraction, the alveolus is flushed with sterile saline and the buccal bone is smoothed with a round bur. The periosteum is incised at the flap attachment if necessary to provide tension closure with 5-0 to 6-0 braided absorbable suture and a cutting needle. The alveolus can be filled with bioabsorbable doxycycline polymer and/or bone regenerative material (Consil®, Nutramax Laboratories) or simply closed. Pain is managed and antibiotics are continued for 6 to 10 days. The patient is rechecked in a week, and follow-up on the atopy is continued.

At a glance

Postsurgical Treatment for Extraction1. Flush the alveolus with sterile saline2. Smooth the buccal bone with a round bur3. Incise the periosteum at the flap attachment if necessary to provide tension closure with5-0 to 6-0 braided absorbable suture and a cutting needle4. Fill the alveolus with bioabsorbable doxycycline polymer and/or bone regenerative material or simply close it5. Manage pain and continue antibiotics for 6 to 10 days.6. Recheck the patient in a week; provide continuous follow-up on the atopy

Take-home messages

In patients with a long-standing fractured upper canine tooth with or without a draining fistula, the tooth probably has a periapical abscess and needs appropriate treatment as soon as possible.

Edema of the muzzle and pruritus should prompt a clinician to look beyond the obvious diagnosis of allergy.