GI ileus occurs when GI contents fail to travel in an aboral direction. Functional obstructions result from decreased peristalsis, and mechanical obstructions are caused by a structural abnormality.1 In small animals, intraluminal mechanical obstructions caused by foreign bodies are most common, but mural and extrinsic causes also occur. Mechanical obstructions may be complete without passage of GI contents or partial with variable amounts of GI contents able to travel aborally.

Mechanical obstructions are often categorized as pyloric outflow, small intestinal, or linear foreign body obstructions.1 Foreign bodies located in the colon rarely cause obstruction and are passed with normal defecation in most cases unless anchored orad as part of a linear foreign body. Radiography can help diagnose foreign body obstructions in most (≈70%) cases and is therefore an excellent screening tool.2 Radiography may be preferable for ruling in a diagnosis of foreign body obstruction because some foreign bodies have opacity similar to GI contents and are therefore difficult to see and some patients do not manifest classic radiographic patterns, making radiography less useful for ruling out a diagnosis. Compared with ultrasonography, radiography requires less technical skill to perform and is faster, less expensive, and more readily available.2

Obtaining Radiographs

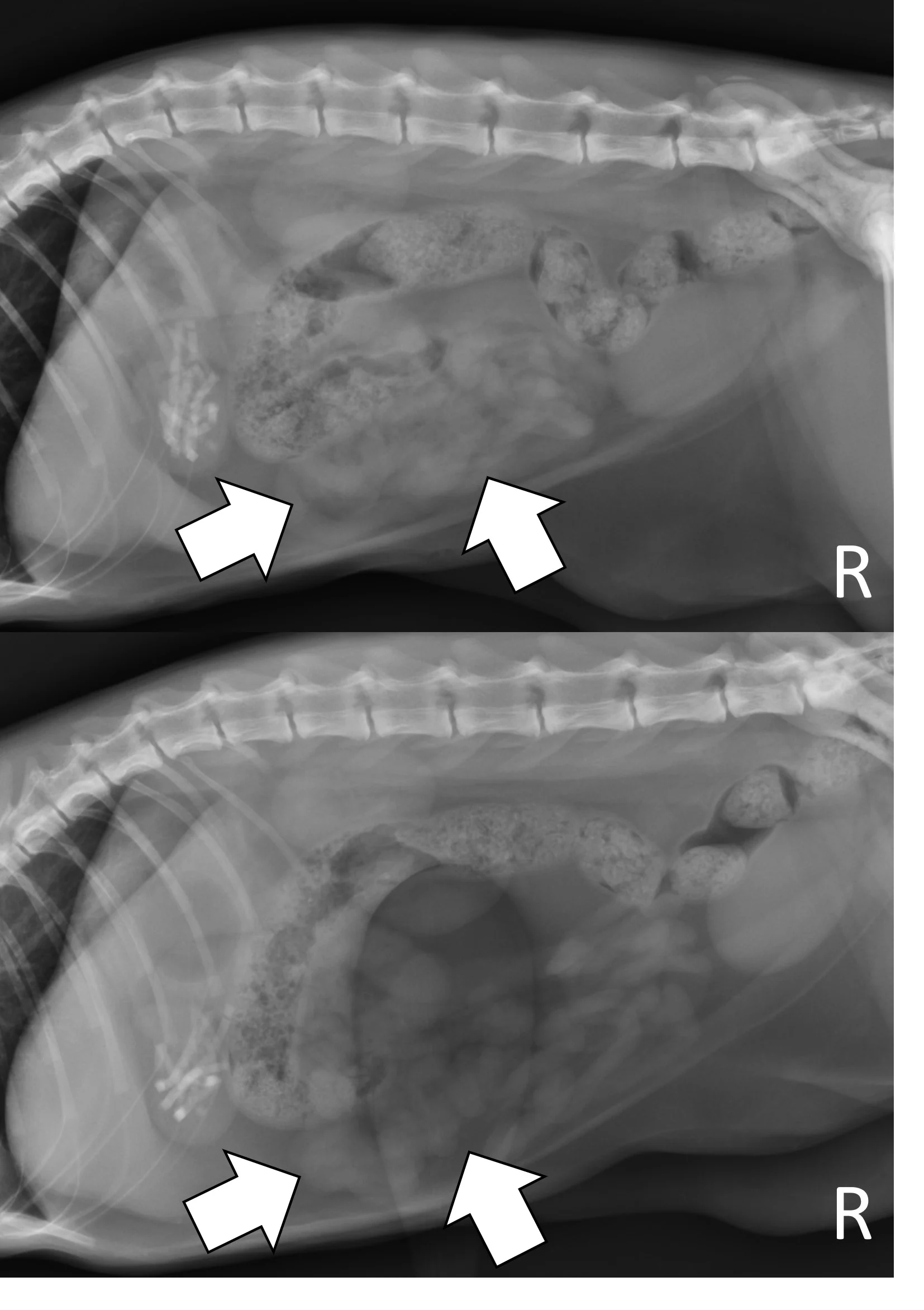

A complete radiographic study includes left lateral, ventrodorsal, and right lateral projections. Obtaining a left lateral projection and performing projections in the aforementioned order can improve visualization of the pylorus and duodenum by shifting gas into the lumens.3 Normal intraluminal gas is an in vivo negative contrast agent that can make soft tissue opaque foreign bodies (eg, cloth) easier to see (Figure 1).

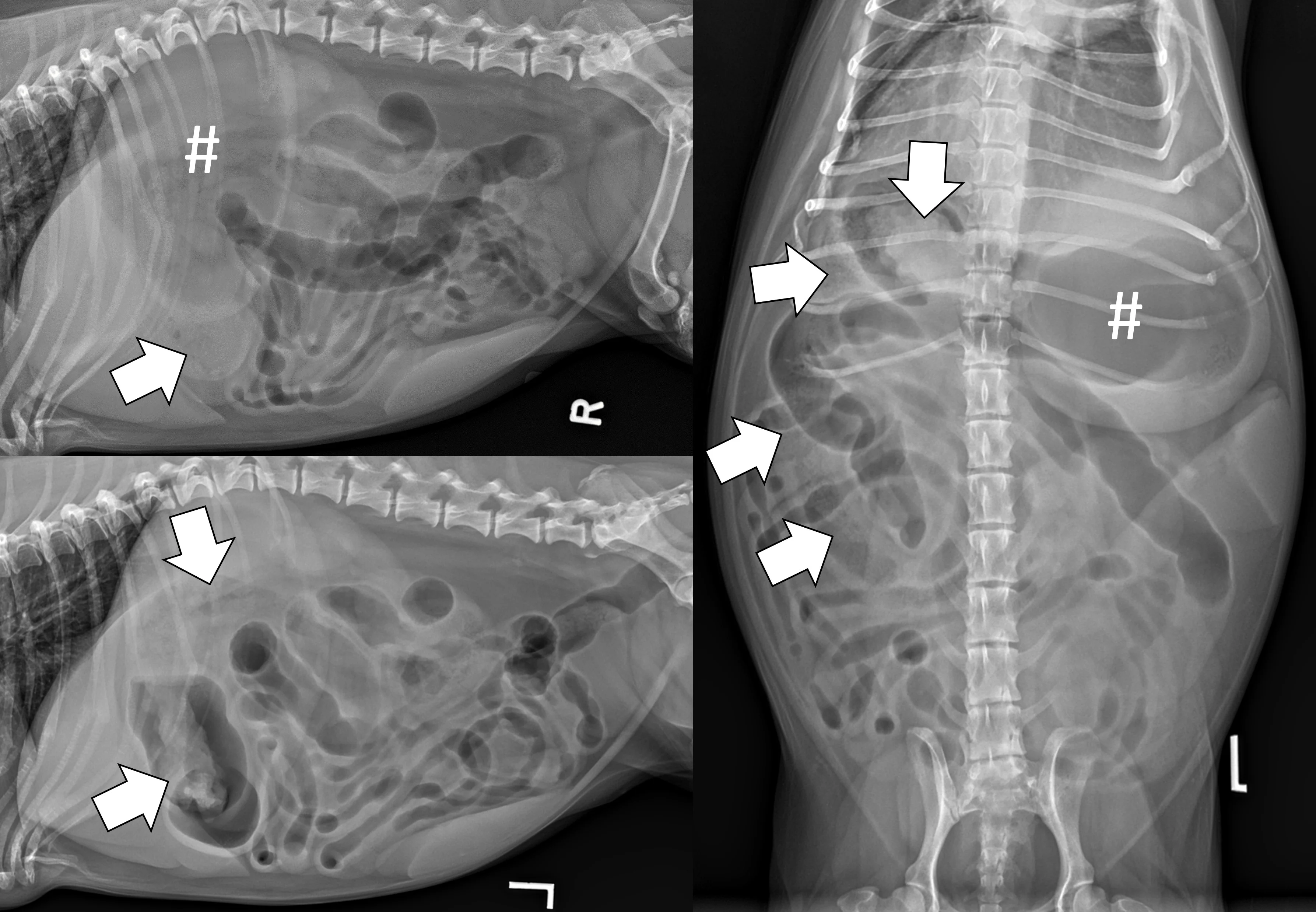

Three-view abdominal radiographs of a 6-year-old spayed dachshund with an acute pyloric outflow obstruction secondary to a surgically confirmed foreign body (cloth). The stomach (pound signs) is moderately dilated with gas and fluid. On the left lateral and ventrodorsal projections, gas outlines an irregularly shaped soft tissue opaque foreign body (arrows) within the pylorus that extends into the duodenum. On the right lateral projection, the foreign body is more difficult to see because it is surrounded by similarly opaque gastric fluid.

Interpreting Abdominal Radiographs for Obstructions

The entirety of the viewable GI tract should be visually traced when interpreting abdominal radiographs for a foreign body obstruction (see Step-by-Step). Emphasizing a clinical question can serve as a final checklist to ensure key radiographic findings are not overlooked. For example, “Is there radiographic evidence of a foreign body or obstructive GI pattern," would be an appropriate question to ask for a young patient with acute vomiting and abdominal pain on physical examination. Asking whether there is evidence of GI perforation would also be appropriate if that same patient has a fever and is clinically unstable. Although it is common to try to answer the primary clinical question first when interpreting radiographs, all abdominal and extra-abdominal structures should also be evaluated. For example, patients with spinal disease can have referral pain that mimics an acute abdomen, and patients with thoracic or metabolic disease can be presented for acute vomiting.

Step-by-Step: Diagnosing Foreign Body Obstructions via Radiography

WHAT YOU WILL NEED

X-ray generator and table

Digital or film detector plate

Right and left laterality markers

Lead gown, gloves, thyroid shield, dosimetry badge

Positioning equipment: V-trough, sandbags, tape, ropes/ties

Sedation (optional)

Noncaffeinated carbonated beverage (optional)

Red rubber catheter (optional)

Lubricating gel (optional)

35- or 60-mL syringe (optional)

Wooden spoon (optional)

Step 1: Obtain Three-View Radiographs

Perform left lateral, ventrodorsal, and right lateral projections.

Author Insight

Information on how to perform three-view abdominal radiography is not included in this article but is available in the literature.4,5

Step 2: Evaluate the Gastric Body

Evaluate the lumen of the gastric body, which is often filled with gas on the right lateral projection.

Step 3: Evaluate the Pylorus

Evaluate the lumen of the pylorus, which is often filled with gas on the ventrodorsal and left lateral projections.

Step 4: Visualize the Duodenum

Visualize the duodenum from the pylorus to the duodenal flexure.

Step 5: Trace the Colon

Trace the colon by starting at the rectum in the pelvic region and following its course to the cecum.

Author Insight

The colon often contains feces, which can help distinguish the colon from the small bowel. Knowing the location, appearance, and dilation of the colon and cecum can help determine whether any remaining loops of dilated bowel are part of the small intestine and of clinical concern.

Step 6: Evaluate the Small Bowel

Evaluate the small bowel located throughout the midabdomen.

Step 7: Evaluate the Peritoneal Space

Evaluate the peritoneal space for decreased serosal detail and/or free gas, the combination of which strongly suggests septic peritonitis secondary to GI perforation (Figure 2).

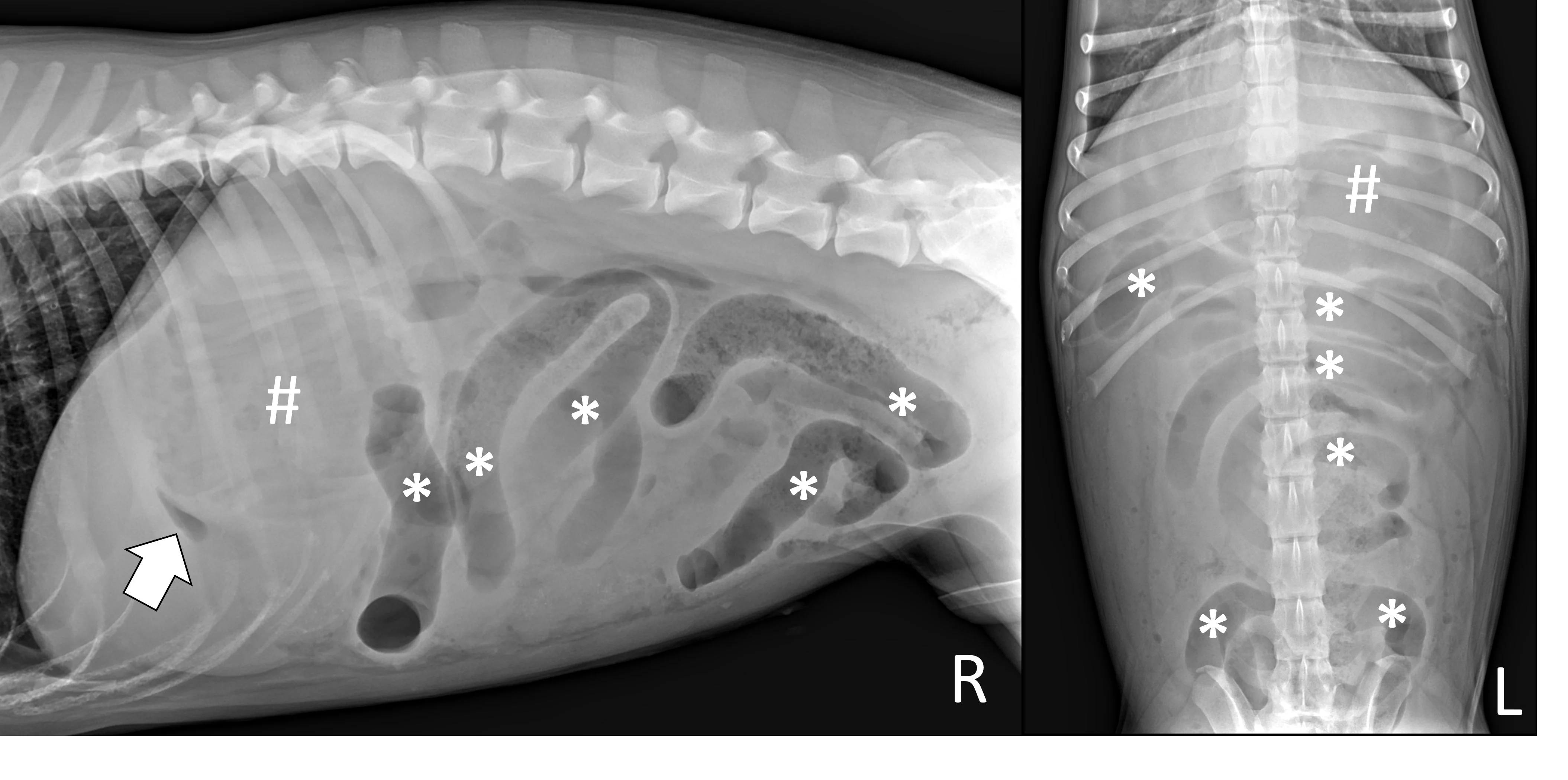

Right lateral and ventrodorsal abdominal radiographs of a 10-month-old neutered male pit bull with a small intestinal mechanical obstruction of undetermined etiology. The stomach is moderately dilated with fluid and gas (pound signs), and there is moderate segmental dilation of the small bowel with stacking and hairpin turns (asterisks). Peritoneal serosal detail is diffusely decreased with a small, tear-drop–shaped intraperitoneal gas bubble between the liver and stomach (arrow) consistent with septic peritonitis secondary to presumed GI perforation.

Step 8: Is a Foreign Body Present?

Determine whether a foreign body can be seen.

Author Insight

Many foreign bodies are mineral or metal opaque and therefore easy to visualize on radiographs. Soft tissue opaque foreign bodies can be seen when outlined with gas. Inability to identify a foreign body does not rule out a mechanical obstruction.

Step 9: Is an Obstructive Pattern Present?

Determine whether an obstructive pattern can be seen.

Author Insight

Each type of foreign body obstruction often causes classic radiographic findings.

Pyloric Outflow Obstructions

Pyloric outflow obstructions occur when a foreign body lodges in the pyloric outflow tract or proximal duodenum and can cause variable gastric distention depending on the length of time the obstruction has occurred and whether the patient has recently vomited, as recent vomiting can reduce gastric size. Although exceptions are possible, acute complete obstructions typically cause mild to moderate gas dilation, and chronic partial obstructions can cause more moderate to severe dilation, predominately with fluid. A gravel sign, characterized by gravity-dependent mineralized ingesta often located in the pyloric antrum, is also possible with chronic partial obstructions (Figure 3).

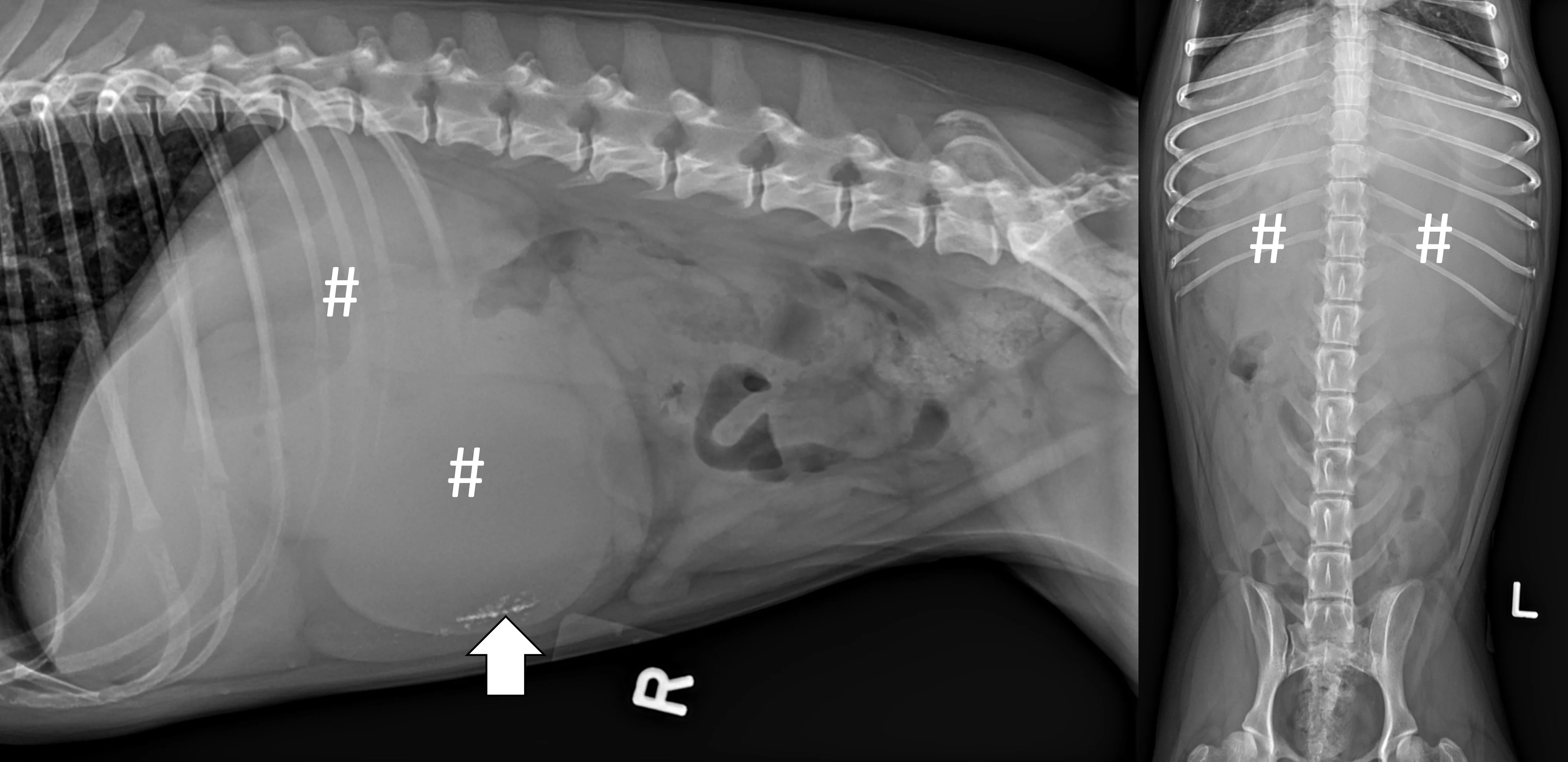

Right lateral and ventrodorsal abdominal radiographs of a 2-year-old spayed Boston terrier with a chronic pyloric outflow obstruction secondary to a surgically confirmed foreign body in the proximal duodenum. The stomach is severely dilated, predominantly with fluid (pound signs). Mineral opaque material located ventrally is consistent with a gravel sign (arrow).

Small Intestinal Mechanical Obstructions

Small intestinal mechanical obstructions occur when a foreign body blocks the lumen of any segment of the small bowel, causing segmental dilation located orad to the foreign body. As the small bowel increases in size, it becomes crowded in the peritoneal space and begins stacking on itself with sharp, hairpin turns (Figure 4).1 Dilated portions of the small bowel usually contain a mixture of fluid and gas. Occasionally, intraluminal gas may outline part of a foreign body, making the object easier to see. Although the diameter of the small intestine can be objectively measured and compared with the height of the center of the L5 vertebral body,6,7 one study found that using the small intestinal diameter:vertebral body height ratio did not increase the diagnostic accuracy for mechanical obstruction on radiographs regardless of clinician experience.8

Right lateral and ventrodorsal abdominal radiographs of a 1-year-old neutered male domestic shorthair cat with a small intestinal mechanical obstruction from a surgically confirmed earplug lodged in the distal jejunum. The stomach is mildly dilated with fluid and gas (pound signs). Segmental fluid and gas dilation of the small bowel with stacking and hairpin turns can be seen (asterisks). On the ventrodorsal projection, intraluminal gas outlines the margin of the earplug (arrow).

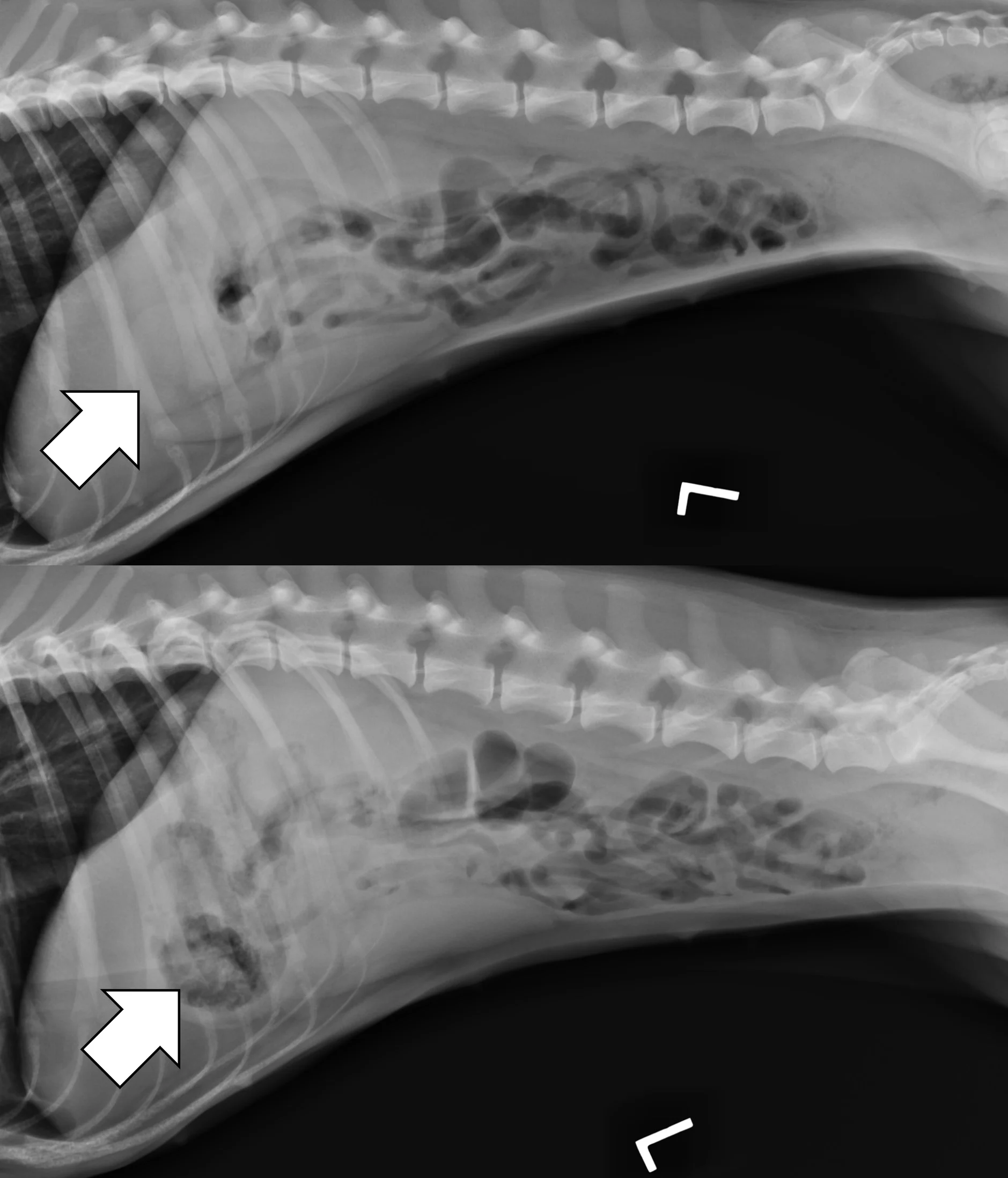

Linear Foreign Body Obstructions

Linear foreign body obstructions occur when an object (eg, string, cloth) becomes stuck orally but extends aborally through the intestinal tract. Peristaltic contractions typically cause the small intestine to travel orally, eventually bunching. As a result, radiographic findings include intestinal bunching (ie, plication; Figures 5 and 6), an undulating serosal border, and angular or crescent-shaped gas bubbles. Obtaining a left lateral projection is critical because many linear foreign bodies anchor in the pylorus.

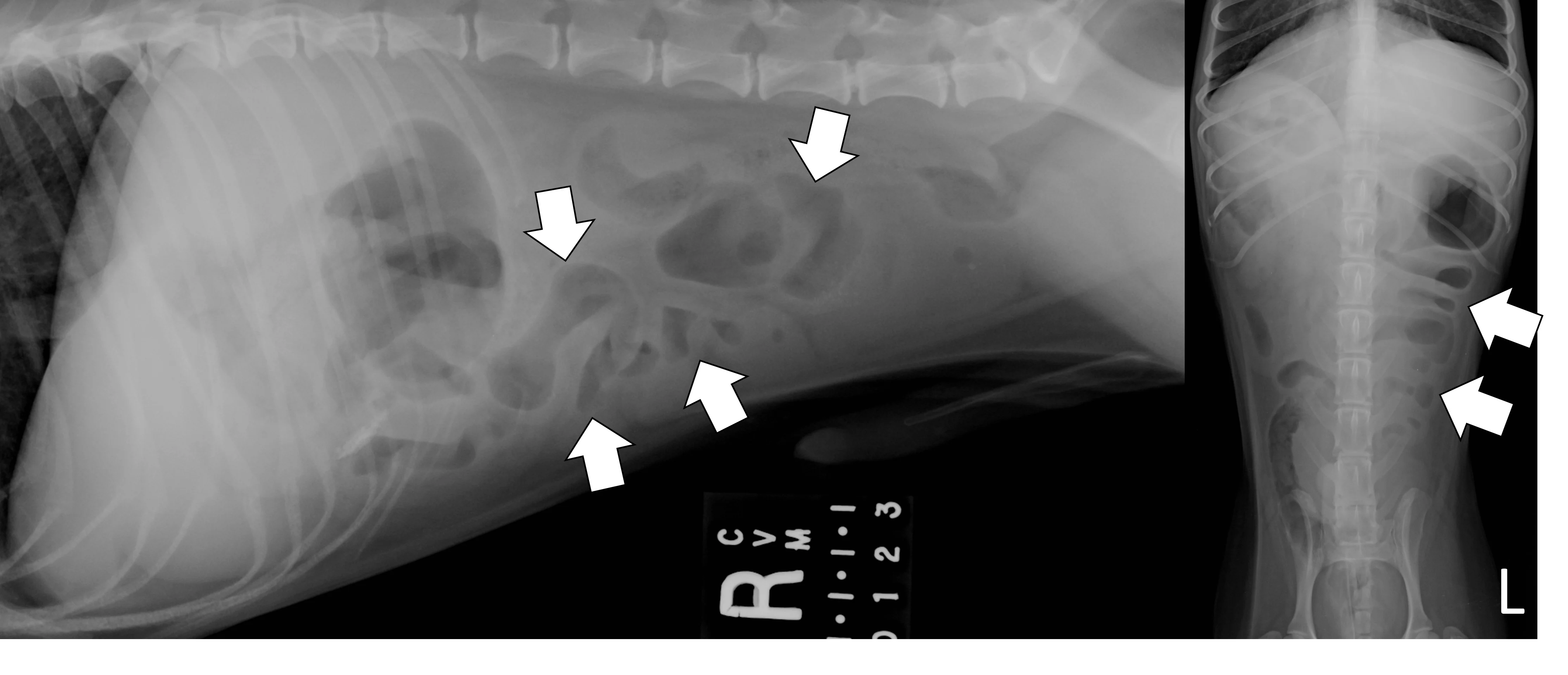

Right lateral and ventrodorsal abdominal radiographs of a male dog (unknown age, breed, and neuter status) with a surgically confirmed acute linear foreign body (cloth) obstruction. Portions of the small bowel are segmentally dilated with bunching and angular or crescent-shaped gas bubbles (arrows).

Right lateral radiographs of a 6-month-old spayed seal point crossbreed cat with a surgically confirmed acute linear foreign body (hair entangled in hair ties) obstruction. The small bowel is bunched in the midabdomen, making the plicated small bowel difficult to see (top, arrows). Normal small bowel displaces after compression with a wooden spoon, but the plicated bowel remains stationary and is easier to see (bottom, arrows).

Step 10: Do Radiographic Findings Match the Clinical Picture?

Determine whether the radiographic findings are consistent with the patient’s clinical picture.

Author Insight

Radiographic findings should be interpreted in the context of all other available data (including patient history, signalment, physical examination findings, and clinicopathologic results) to help ensure accurate diagnosis.9,10 For example, not all foreign bodies are obstructive. A foreign body or suspicious gas pattern may be less important in a dog that is bright and alert, lacks abdominal pain, and is not vomiting, or surgery may be indicated despite inconclusive imaging results in a patient that is progressively painful in the abdomen or vomiting after receiving antiemetic therapy. Including pertinent case information is especially important when seeking consultation from a radiologist or other specialist, as this information may influence their interpretation and clinical recommendations.

Additional Radiographic Techniques That Make Diagnosing Obstructions Easier

Additional radiographic techniques that are fast, safe, inexpensive, and easy to perform can make diagnosing obstructions via radiography easier in specific clinical situations if a standard 3-view study is equivocal.

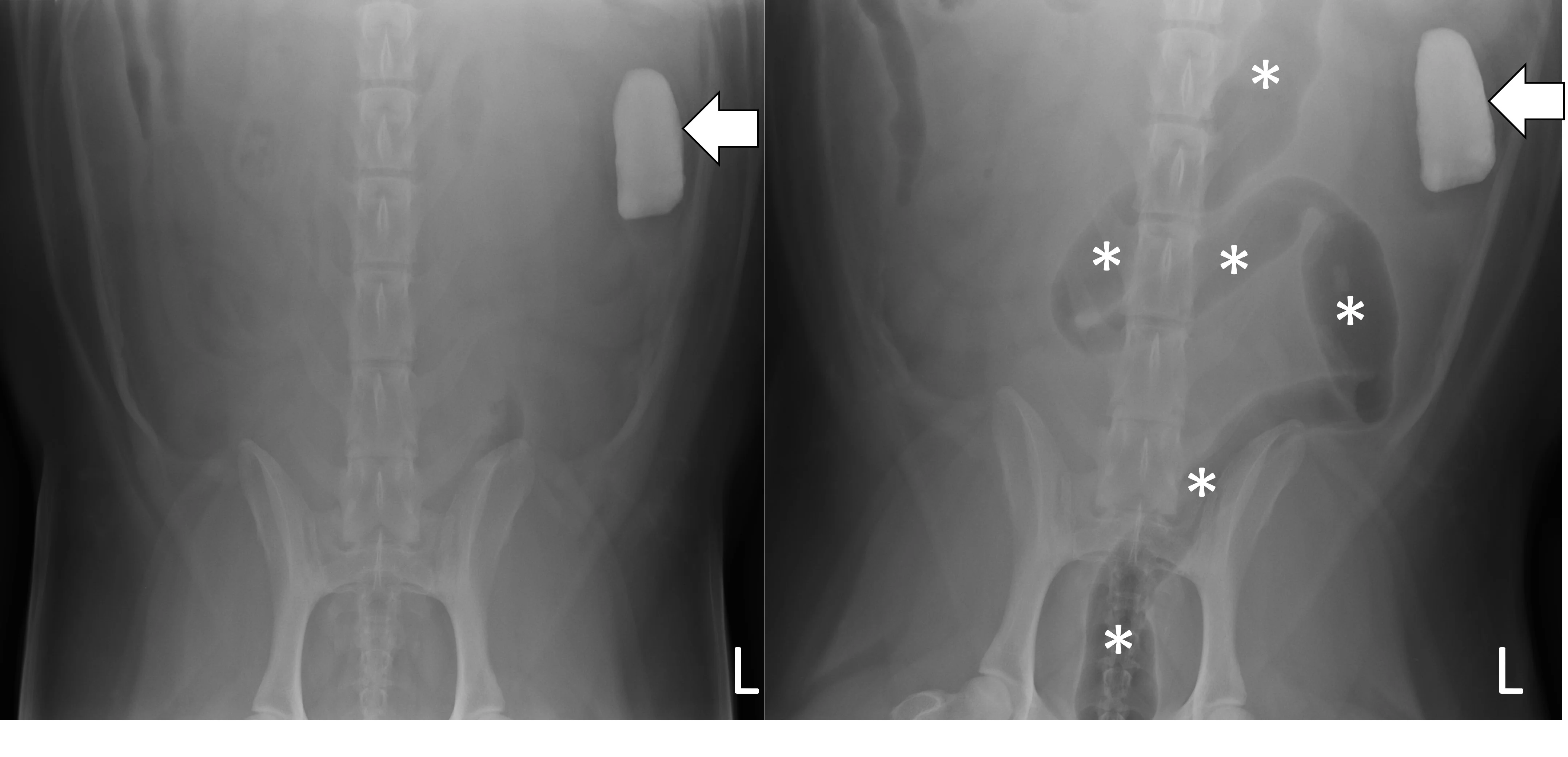

Pneumocolonogram

A pneumocolonogram can be performed to determine whether a foreign body is located in the colon or whether a focally dilated loop of intestine is part of the small bowel or colon (Figure 7).11 Sedation is often not necessary but can be used in uncooperative patients. Room air (3 mL/kg) should be administered into the rectum with an appropriately sized and lubricated red rubber catheter and syringe. Right lateral and ventrodorsal projections should be obtained immediately. The goal is to mildly dilate the entirety of the colon to the cecum with gas without overfilling the small intestine. The dose of air may need to be repeated to effect in some patients if there is inadequate filling of the entire colon.

Ventrodorsal radiographs of a 3-year-old spayed golden retriever with a small intestinal obstruction secondary to rock ingestion. Survey radiographs revealed the rock was in the left lateral abdomen but could not help determine whether the rock was in the small bowel or the descending colon (left, arrow). Pneumocolonogram was performed to mildly dilate the colon with gas (asterisks), confirming the rock was in the small bowel (right, arrow).

Modified Pneumogastrogram

A modified pneumogastrogram can be performed if there is insufficient gas in the stomach to fill the pylorus on the left lateral projection.12 A noncaffeinated carbonated beverage (60 mL; author reduces to 30 mL in patients <11 lb [5 kg]) should be given and a left lateral projection obtained immediately (Figure 8). The beverage may be administered free choice or via syringe if the patient is unwilling to drink. A modified pneumogastrogram produces less gas compared with traditional pneumogastrogram but is usually effective and avoids the need for placing an orogastric tube.

Left lateral radiographs of a 1-year-old spayed crossbreed dog with a pyloric outflow obstruction secondary to ingestion of part of a soft tissue opaque toy bone. On survey radiographs, there was insufficient gas in the stomach to fill the pylorus on the left lateral projection, masking the foreign body (top, arrow). A modified pneumogastrogram with a carbonated beverage was performed, resulting in the foreign body being outlined by gas and easily seen (bottom, arrow).

Additional Projections With Compression

In some patients, especially those that are obese, the small bowel loosely bunches, raising concern for a linear foreign body obstruction. Obtaining a lateral and/or ventrodorsal radiograph while gently compressing the region of concern with a wooden spoon can help differentiate physiologically bunched small intestine (easily disperses) from plicated bowel (does not disperse).

Listen to the Podcast

Dr. Seitz joined the podcast to share his expertise on how to use radiography to the fullest and how to apply point-of-care ultrasound at the general practice level.