Feline Enteric Coronavirus & FIP

Jarod M. Hanson, DVM, PhD, DACVPM, DABT, University of Maryland

Feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) is an Alphacoronavirus, unlike severe acute respiratory sydrome coronavirus 2 (ie, SARS-CoV-2) and canine respiratory coronavirus, which are Betacoronaviruses.1 FECV typically causes mild, often subclinical GI illness through infection of enterocytes2; however, a multifactorial process that relies on viral mutations (eg, spike gene mutations3,4) in the host during persistent infection can cause FECV to lose tropism for enterocytes and preferentially infect monocytes and macrophages. This change induces a dysregulated immune response, leading to FIP. The cause of the viral mutations is unclear.

Serotypes

Feline coronavirus has 2 serotypes, both of which can cause the wet or dry form of FIP. Serotype I viruses likely originated in the United States and spread internationally as the predominant serotype.5,6 Type I viruses demonstrate a lack of crossprotection with serotype II strains, complicating vaccine development (see Prevention & Treatment).7

Transmission

FECV is transmitted via multiple routes, including fecal–oral, blood, and other body fluids.8 Vertical transmission from queens to kittens is common and likely occurs before 16 weeks of age.8 Sexual transmission from intact males is unlikely; seropositive males may have FECV viruses or viral fragments in testicular tissue, but it is not clear if or when this material may be shed in the semen.9

Although most cats become infected with FECV, long-term disease is uncommon. FIP is not caused by transmission of FECV alone; persistent infection and viral mutations that allow the virus to preferentially infect monocytes and macrophages is necessary. Unmutated FECV can infect monocytes and macrophages but preferentially infects enterocytes.10 Risk factors for FIP include stress, age, immunosuppressive infections, and genetic predisposition.11-13 FIP occurs in ≈5% to 10% of cats with FECV and <1% of cats admitted to veterinary hospitals.14

Clinical Signs

FIP typically occurs in young or old cats but can occur in cats of any age and affects both domestic and wild felid species.2,15

The wet form of FIP is characterized by cavitary effusion (Figures 1 and 2) and can cause pyogranulomatous inflammation in one or more organs. The dry form typically results in variably sized pyogranulomas in affected organs and does not cause cavitary effusion.2 Lesions can include atypical presentations (eg, ocular, neurologic, ileocolic, rhinitis).2,16

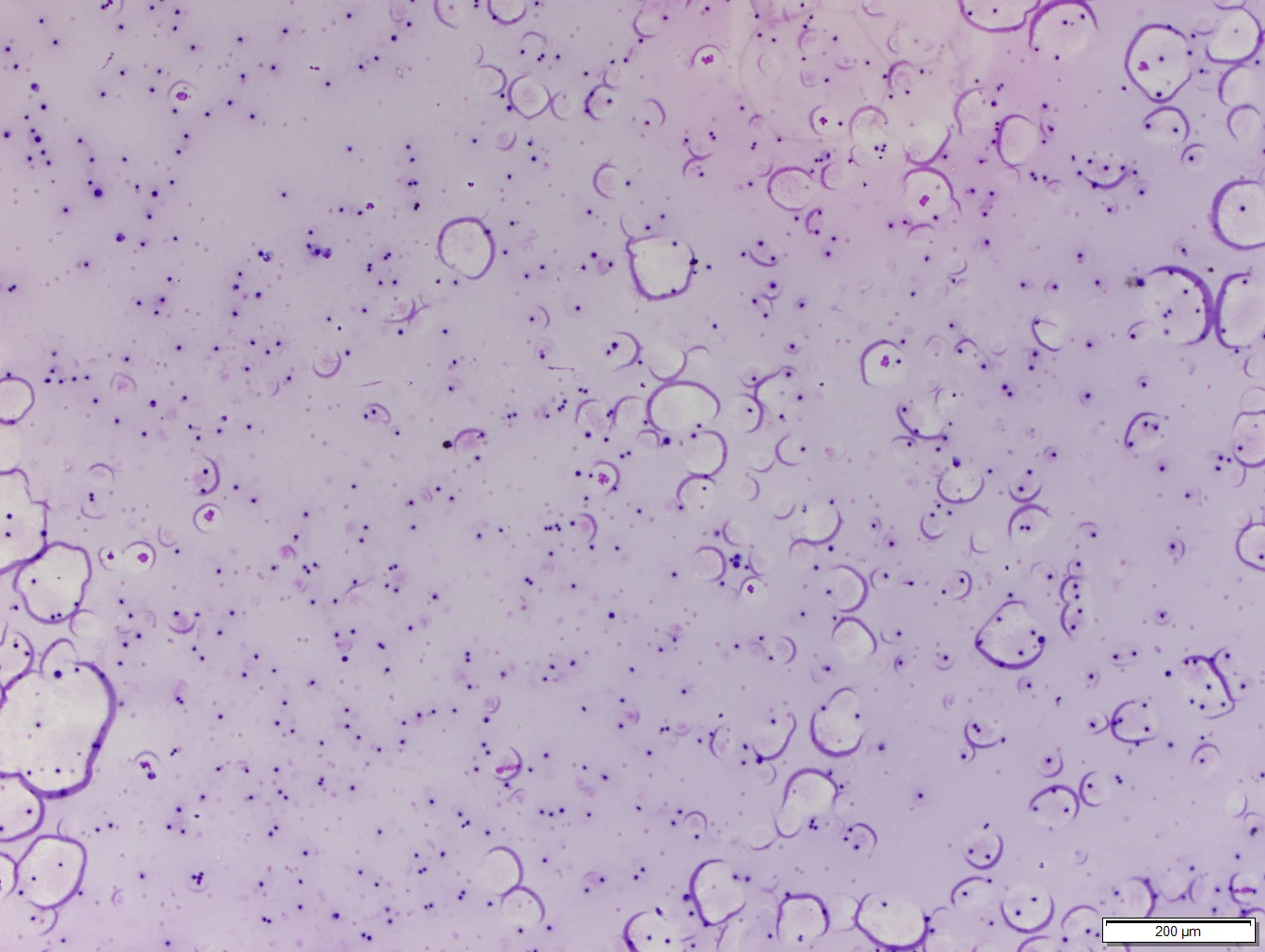

FIGURE 1

Crescent moon/semicircle-shaped protein aggregates that are classic features of proteinaceous wet FIP effusions. 10× magnification. Image courtesy of Bridget Garner, DVM, PhD, DACVP (Clinical Pathology)

Pathogenesis

Infected monocytes and macrophages recruit additional monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils via cytokines and inflammatory mediators (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase-9) that cause enhanced vascular permeability.17,18 Type III and IV hypersensitivity reactions may also increase vascular permeability and/or granuloma formation.2

Diagnosis

Diagnosis via serology or reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) of infectious materials can be difficult, as subclinical cats may have high titers and severely ill cats may have no titers. Cats with FIP typically exhibit higher coronavirus titers than cats with FECV that are not persistently infected.18

Cats are often infected with multiple variants of FECV, most of which are benign and create false-positive results if primers do not adequately target likely mutation sites. PCR should therefore be specific enough to identify FIP variants without missing unique mutations. These mutations can also cause FIP but are outside the boundaries of PCR primers used on the S gene, which can generate false-negative results.3,19 RT-PCR results should be verified via biopsy with immunohistochemistry.20 Sequencing the S gene allows all mutations in the S gene to be identified but is not widely available; results should be interpreted in conjunction with other diagnostic results.

Surgical biopsy with histopathology or fine-needle aspiration with cytology of affected organs is often used with immunohistochemistry to support diagnosis and determine disease stage.21 Full fluid analysis of cavitary effusions associated with FIP commonly demonstrates yellow, viscous fluid with an elevated protein concentration (>3.5 g/dL) and disproportionately low cell count.22 Fluid analysis in addition to other diagnostics (eg, serology, RT-PCR, fine-needle aspiration) performed on a variety of tissues can increase the probability of confirming diagnosis of FIP based on cumulative test results, signalment, and patient history.3 Histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and RT-PCR have 40% to 85% sensitivity and 83% to 100% specificity (depending on tissue type), reinforcing the need for a multifaceted diagnostic approach.20,21

Prognosis

The mortality rate of FIP has been >95% but is likely decreasing with new treatment options.23,24

Prevention & Treatment

FIP vaccines are available but not recommended by AAFP or AAHA due to lack of crossneutralization (vaccine contains serotype II virus only).7,25 In addition, the vaccine is labeled for administration at 16 weeks of age, at which point kittens are likely already infected by queens.7 Antibody-dependent enhancement of disease has been observed experimentally but has not been noted during natural infection or vaccine field studies.25 Despite these concerns, vaccination may be clinically useful in limited situations (eg, catteries, other dense populations when introducing naive cats).25

Control of FECV and FIP via isolation of persistently infected cats to interrupt the transmission cycle can be attempted but is not likely to be effective in multicat environments.

Experimental antiviral drugs have some efficacy for treatment of FIP,26-30 and nonnucleoside analogues (eg, ERDRP-0519, GS-441524, remdesivir) are emerging as possible treatment options.<sup27,31,32 sup>