An Overview of Feline Aortic Thromboembolism

Profile

DefinitionFeline aortic thromboembolism (FATE) is a clinical syndrome associated with systemic embolization of cardiac thrombi (it is strongly suspected, but not proven, that peripheral thrombosis is secondary to embolization, rather than a localized thrombotic process). Any part of the systemic vasculature can be embolized. Most TE occlude the aortoiliac bifurcation (aortic saddle; Figure 1). Ischemic necrosis of the embolized organ or tissue results. Most FATE occurs secondary to HCM, UCM, and occasionally DCM (rare these days). Cases of FATE can occur without identifiable underlying disease, in conjunction with noncardiac hypercoagulable states (eg, proteinuric nephropathy, neoplasia), or may be secondary to hyperthyroidism.

Genetic Implications

HCM is considered to have a genetic basis in humans and many cats.

Genetic mutation has only been identified in Maine coons (www.vetmed.wsu.edu/deptsVCGL); testing is available for this breed.

No specific genetic predisposition has been suspected for FATE.

Incidence/PrevalenceNo published articles have accurately determined the incidence or prevalence of FATE. While some articles have suggested that the incidence is as high as 35% to 50% of HCM cases, anecdotal evidence and my experience suggest that fewer than 10% of cats with HCM develop FATE.

Geographic DistributionWorldwide

Signalment

Breeds at risk for HCM are at risk for FATE: Maine coons, Persians, Burmese, Siamese, American shorthairs, ragdolls, Norwegian forest cats, Scottish folds, Turkish vans, British shorthairs, Abyssinians, Birmans.

Adult

No gender predisposition

Causes

Severe HCM, UCM, or DCM predisposes to FATE.

Hyperthyroidism

Disorders resulting in hypercoagulability (eg, proteinuric nephropathy, neoplasia)

Risk Factors

Specific risk factors in FATE have not been critically examined.

Suspected risk factors include severe HCM, DCM or UCM:

With left atrial thrombus-a reasonable hypothesis, because the patient is displaying evidence of thrombogenic potential and a nidus for TE

With spontaneous left atrial echogenic contrast (ie, "smoke")-evidence of blood stasis, providing an environment for thrombosis

Less specific risk factors include severe HCM, DCM, or UCM with severe left atrial enlargement (One recent study suggests left atrial size may not be an independent risk factor.).

In noncardiac FATE, proteinuria and loss of ATIII are risk factors.

SignsHistory

Acute hemiparesis or paraparesis is the most common historical finding.

Paresis of individual forelimbs is also reported.

Owners often report cat "howling and suddenly collapsing."

There is a history of heart disease.

Severe malaise can occur with renal or intestinal ischemia.

Physical Examination

Specific findings depend on the affected organ or tissue and severity of vascular compromise.

Presentation is usually acute.

Signs of CHF may be present.

Tachypnea is common (pain-, stress-, or CHF-related).

Hypothermia (due to lack of rectal blood flow)

Pain will be present if TE is acute (ie, < 24 hrs).

Embolization of limbs results in loss of motor and sensory function (paresis or paralysis), depending on degree of vascular compromise.

Muscles distal to TE become hard and swollen.

Affected distal extremities may be cool.

Footpads may be cyanotic.

Claws in affected limbs may fail to bleed if clipped. This test can be done if deep pain is absent-otherwise, it is a painful diagnostic procedure.

Pulses in affected limbs may be undetectable with Doppler flow probes or digital palpation.

Heart murmurs, arrhythmias, gallop sounds may be ausculted, confirming presence of heart disease; most but not all cats have detectable signs of heart disease.

Pain Index

Often severe with acute embolization and ischemic myopathy

Subsides with time because of associated ischemic sensory neuropathy

May increase with acute reperfusion

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Largely based on physical examination findings (see above)

Imaging studies can help in some cases.

Differential Diagnosis

Other causes of acute limb dysfunction should be ruled out.

Motor vehicle or other trauma resulting in spinal or limb fracture can have similar presentation. Usually, motor vehicle trauma results in "shattered" claws and other external signs of injury. Blood flow to affected limbs is usually normal in these cases. Some cats self-mutilate due to pain associated with FATE. The diagnosis of FATE should not be eliminated based simply on the presence of external wounds.

Intervertebral disc herniation is rare in cats and usually nonpainful.

Onset of spinal tumors is usually more gradual.

Thiamine deficiency or hypokalemia usually does not cause paralysis.

Laboratory Findings/Imaging

Stress hyperglycemia

Elevations in muscle enzymes:

Marked elevations in creatine kinase (sometimes > 100,000 mg/dl)

Elevations in aspartate aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase

Hyperkalemia may be present if reperfusion has occurred before sampling and can be life-threatening.

Azotemia may be present if renal arteries are obstructed or if cat is dehydrated.

Ultrasonography (color-flow Doppler) of affected vasculature may reveal thrombus or lack of blood flow.

Contrast angiography can demonstrate vascular occlusion; however, this is a high-risk procedure and is not recommended.

Echocardiography can confirm the presence of substantial cardiac disease and potentially intracardiac thrombi.

Postmortem Findings

Thromboembolism can occasionally be found if necropsy is done immediately (Figure 1, A postmortem dissection of a saddle thrombus at the bifurcation of the iliac arteries).

Heart disease is often identifiable, with a large left atrium.

Atrial thrombosis can occasionally be found (the thrombus is commonly lodged in the left auricle).

Affected ischemic muscles may appear blanched or different from unaffected muscles.

Treatment

FATE requires hospitalization in virtually all cases, especially those with CHF, paralysis, and pain. Patients can be discharged once clinical signs are controlled and pain has been alleviated.

ActivityShould be confined during recovery. Physical therapy may be attempted for affected limbs.

Client EducationClients should be advised of the severity of the condition, the often prolonged and incomplete recovery, and the high probability of recurrence or death from cardiac causes.

Surgery

Surgical TE removal has been attempted in the past with uniformly dismal results and should not be undertaken.

Amputation or wound management of ischemic and necrotic tissue may be necessary during long-term management.

Acute Therapy

Pain relief is essential in acute FATE. Narcotic analgesia is advised, by epidural, transdermal, or parenteral methods.

Reperfusion hyperkalemia can be life-threatening with rapid reperfusion and should be carefully monitored. Glucose/nsulin and calcium gluconate administration may be required to control hyperkalemia.

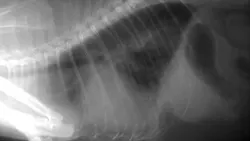

CHF (Figure 2, Lateral thoracic radiograph of a cat with dyspnea. A heavy pulmonary interstitial pattern and marked cardiomegaly, consistent with CHF, are apparent. Gas in the stomach is suggestive of aerophagia associated with dyspnea.) should be treated when necessary by diuresis with furosemide. Other cardiac medications have little utility in acute management of CHF in cats. Pleurocentesis may be necessary if pleural effusion is present.

Oxygen therapy may be necessary if CHF is present.

Fluid therapy should be administered cautiously; most cats have substantial cardiac disease and cannot tolerate fluid loading.

Thrombolytic therapy is currently not recommended because of high mortality with reperfusion injury. No studies demonstrate clinical benefit of streptokinase infusions. Two studies demonstrated 50% acute mortality from reperfusion injury with tissue plasminogen activator infusion or streptokinase administration due to rapid thrombolysis. A recent study using rheolytic thrombectomy also showed a 50% acute mortality.

Vasodilator therapy does not appear to be effective in promoting collateral circulation. Acepromazine fails to promote collateral circulation and can tranquilize the patient excessively. Hydralazine also is of little value. Serotonin antagonists (eg, cyproheptadine) prevent collateral vasoconstriction only if administered before-not after-thromboembolism.

Chronic Therapy

CHF should be treated as necessary-furosemide (1-4 mg/kg Q 8-24 H) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (0.5 mg/kg Q 12-24 H) should be administered.

Hyperthyroidism should be treated by radioiodine therapy or methimazole.

Antithrombotic agents can be used to try to minimize further thrombosis or prevent recurrence.

None of the antithrombotics listed below have been shown to be effective in preventing initial FATE, or recurrence of FATE in HCM.

Aspirin can be administered at 5 mg/cat Q 72 H; higher doses have more side effects and no additional benefit.

Heparin is not recommended; hemorrhagic complications can occur.

LMWHs (100 U/kg Q 12-24 H SC) inhibit factor Xa. They cause fewer complications than unfractionated heparin and are considered safe in cats.

Warfarin (0.2-0.5 mg/day PO) depletes vitamin-K-dependent coagulation factors and is not recommended.

Clopidogrel (18.75 mg Q 24 H PO) is a platelet-activation inhibitor that blocks the ADP receptor on unactivated platelets, preventing ADP-mediated activation. Few clinical side effects have been documented. A clinical trial examining the efficacy of clopidogrel in preventing recurrence of FATE (FAT CAT) is currently ongoing and recruiting cases (www.vin.com/fatcat/). Aspirin can be given safely with clopidogrel.

ContraindicationsThrombolytic therapies are generally contraindicated in acute management of FATE.

Precautions

Animals receiving antithrombotics should be monitored for hemorrhage.

Newer-generation antithrombotics do not seem to cause as many complications.

Interactions

Antithrombotics should not be combined (other than with aspirin).

Warfarin has many interactions with other medications-its use is not recommended for this and other reasons.

Alternative TherapyPhysiotherapy of affected limbs can be attempted-massage and joint manipulation may stimulate collateral circulation once pain has subsided.

Nutritional Aspects

Nasogastric feeding may be required during acute management if patients are anorexic. Food administered by nasogastric tubes should be included in daily fluid balance calculations.

If DCM is identified, plasma taurine concentrations should be measured and taurine should be supplemented if necessary; however, taurine-deficient DCM is rare.

Follow-up

Inpatient Monitoring

Respiratory rate and effort should be monitored for CHF resolution or development.

Serum potassium concentrations should be monitored for evidence of reperfusion hyperkalemia, especially if sudden return of limb function occurs.

Outpatient

Newer antithrombotics do not require coagulation monitoring.

Affected limbs should be monitored for return of function and tissue necrosis.

PreventionNo therapies have been shown to prevent FATE or HCM. Many cardiologists administer antithrombotics prophylactically to "at-risk" cats, but this practice has no clinical basis.

Complications

Recurrence of FATE is common. Subsequent episodes are often milder, but can be life-threatening.

Hemorrhagic complications can occur with heparin or warfarin therapy, but have not been reported with LMWH or clopidogrel at this time.

Course

Recovery of limb function can occur in hours, but can take several weeks.

In most cats that regain function, substantial return of blood flow and partial return of function is evident within 2 weeks.

Recovery may never be complete, or may be unilateral.

At-Home Treatment

Administration of medications for chronic management

Physical therapy during convalescence

In General

Relative Cost

$$-$$ for acute management

$-$ for monthly antithrombotic medication

Prognosis

Approximately 50% of cats survive to discharge (with or without CHF).

Cats with hypothermia at presentation have worse prognosis.

Long-term survival is poor-50% of cats discharged die or have rethrombosis within 4 months; recurrence can occur within 2.5 months in cats with CHF at presentation. A total of 90% of cats that survived to discharge in one study had rethrombosis or died within 6 months.

No critical survival data are available for cats treated with LMWH or clopidogrel. In one study, 50% of cats treated with LMWH survived for 6 months, but no control group was included. Another study by the same authors found the same survival rate in cats not treated with LMWH.

Future Considerations

Studies of clinical outcomes with most chronic therapies are lacking for FATE. FAT CAT is the first randomized trial to examine efficacy of antithrombotic agents in preventing recurrence of FATE. Participation is strongly encouraged. Practitioners retain management of their patients.

Rheolytic thrombectomy, which requires arterial access, has been recently performed successfully in 5 of 6 cats, but only 3 survived to discharge.

Estimates of left atrial appendage (left auricle) flow by Doppler echocardiography may help identify cats at risk for left atrial thrombosis and stratify patients for appropriate therapy.

TX at a glance ...

Treat FATE episodes with opioid analgesics-buprenorphine (0.01-0.03 mg/kg IM, IV, or buccal [well accepted by cats]). Effects may last up to 6 hours. Butorphanol (0.1-1 mg/kg IM, IV, SC Q 1-3 H) or oxymorphone (0.05-0.1 mg/kg IV, IM, SC Q 2-4 H) can also be used.

Treat concurrent acute CHF with furosemide (1-4 mg/kg IV or IM Q 8-24 H), oxygen, and pleurocentesis if necessary. Treat chronic CHF with furosemide and ACE-inhibitors as necessary.

Treat reperfusion hyperkalemia aggressively if TE lyses rapidly.

Avoid mechanical/surgical or medical thrombolysis.

Allow 2-6 weeks for spontaneous thrombolysis or development of collateral circulation and (at least partial) return of function.

Consider antithrombotics to prevent recurrence-LMWHs or clopidogrel +/- aspirin.

Editor's note: This article was originally published in November 2006 as "Feline Aortic Thromboembolism"

FELINE AORTIC THROMBOEMBOLISM • Mark Rishniw

Suggested Reading

Arterial thromboembolism in cats: Acute crisis in 127 cases (1992-2001) and long-term management with low-dose aspirin in 24 cases. Smith SA, Tobias AH, Jacob KA, et al. J Vet Intern Med 7:73-83, 2003.Feline distal aortic thromboembolism: A review of 44 cases (1990-1998). Schoeman JP. J Feline Med Surg 1:221-231, 1999.Population and survival characteristics of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: 260 cases (1990-1999). Rush JE, Freeman LM, Fenollosa NK, Brown DJ. JAVMA 220:202-207, 2002.Thromboembolic disease. Kittleson MD. In Kittleson MD, Kienle RD (eds): Small Animal Cardiovascular Medicine-Veterinary Information Network; accessed May 23, 2006. www.vin.com/Members/Proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=SACARDIO& Category=1592&O=VINUltrasonographic diagnosis-Small bowel infarction in a cat. Wallack ST, Hornof WJ, Herrgesell EJ. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 44:81-85, 2003.Use of low molecular weight heparin in cats: 57 cases (1999-2003). Smith CE, Rozanski EA, Freeman LM. JAVMA 225:1237-1241, 2004.