Feline atopic skin syndrome (FASS) is an allergic skin disease caused by exposure to food and environmental allergens, potentially including pollens (eg, grass, weed, tree), molds, and mites (eg, dust mites, storage mites).1 Presentation may include one or more of the following feline hypersensitivity reaction patterns: head and neck pruritus, miliary dermatitis, eosinophilic granuloma complex (eg, eosinophilic granuloma, eosinophilic plaques, indolent ulcers), self-induced alopecia (from overgrooming and/or barbering; Figures 1-3).1

FIGURE 1

Self-induced alopecia without inflammation on the ventral chest and abdomen of a middle-aged, domestic shorthair cat

How should environmentally caused feline atopic skin syndrome be diagnosed and treated?

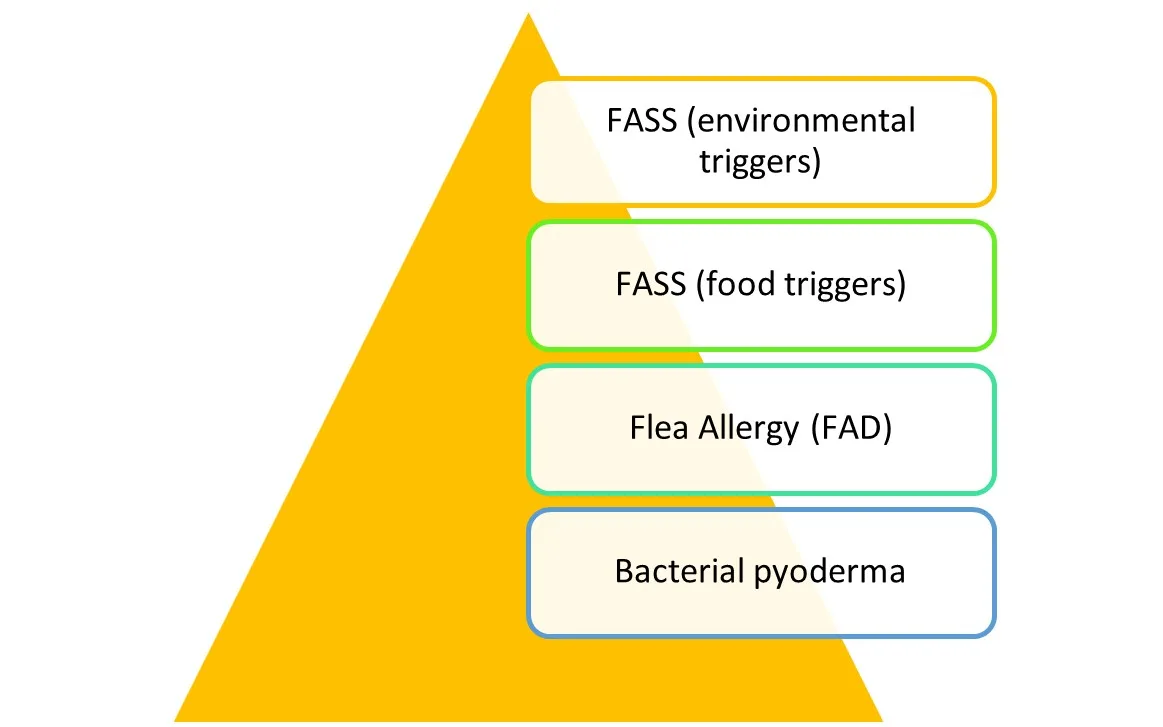

Clinical signs of allergic skin disease typically follow one or multiple feline hypersensitivity reaction patterns and are often worse in cases in which multiple causes of allergy and secondary bacterial pyoderma are present. The burden/disease severity of environmental FASS may be less severe and require less intensive management if food allergy, flea allergy, contagious ectoparasites, and secondary infection are controlled (Figure 4). Most affected cats have clinical signs by 3 years of age, and nonseasonal signs are more common than seasonal signs.1,2

Severity of itch decreases as pruritic components are managed in cats with multiple causes of pruritus with overlapping clinical signs.

Diagnosis

FASS caused by environmental triggers is identical to FASS caused by food triggers and has overlapping clinical signs with flea allergy dermatitis and nonallergic skin conditions (eg, dermatophytosis, ectoparasites, pemphigus foliaceus) in some patients.1 Environmental FASS is a diagnosis of exclusion once other causes of pruritus have been ruled out or concurrently managed. Pruritic ectoparasites that cause skin lesions (including fleas, Notoedres cati, and Demodex gatoi) should be ruled out with use of an isoxazoline preventive. Ectoparasite prevention should continue year-round. FASS caused by food allergy should be ruled out in all patients with nonseasonal signs or during the initial months of treatment if seasonality has not been established (see Workflow for Pruritic Cats With Clinical Signs That Match Allergic Skin Disease).

Flea and food allergies should be ruled out as components of pruritus or controlled year-round (when present) to evaluate the effectiveness of FASS therapy.

Workflow for Pruritic Cats With Clinical Signs That Match Allergic Skin Disease

Step 1

Rule dermatophytosis in or out

Rule out or provide trial treatment for ectoparasites

Treat secondary skin infections based on cytology results

Consider use of antipruritic medications (eg, corticosteroids [eg, prednisolone])

Step 2

Rule food allergy in or out

Treat secondary skin infections based on cytology results

Consider use of antipruritic medications (eg, corticosteroids [eg, prednisolone])

Step 3

FASS is likely; create a long-term treatment plan with antipruritic medications, environmental allergy testing, and immunotherapy

Continue with steps 1 through 3 until clinical signs are adequately controlled.

Treatment

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are a first-line treatment for acute flares of FASS and a practical option for patients with a low number of yearly flares. Corticosteroids can also be used to relieve pruritus during diagnostic investigation for FASS. The author’s goal is to limit corticosteroids to 90 anti-inflammatory doses per year in cats with chronic FASS; for example, a cat may receive corticosteroids every other day from April 1 through July 30, 1 to 2 doses per week year-round, or depot methylprednisolone 3 or fewer times per year.

When possible, oral corticosteroids are preferred over long-acting injectable corticosteroids to reduce adverse effects and allow for tapering. Corticosteroid anti-inflammatory doses for cats are higher than for dogs; initial prednisolone doses are 1 to 2 mg/kg PO every 24 hours or equivalent.3 Noncorticosteroid allergy control medications (Table) are recommended to reduce or eliminate the need for corticosteroids in patients with chronic FASS.

Table: Noncorticosteroid Treatment Options for Feline Atopic Skin Syndrome

Modified Cyclosporine

Modified cyclosporine is consistently effective (success rates, >70%) at controlling FASS.3-5 Modified cyclosporine is likely most useful in patients with year-round clinical signs or longer periods of pruritus. Patients with seasonal pruritus may require a different administration frequency at different times of the year.

Adverse effects occur in ≈17% to 60% of cats but are generally mild.3-6 The most common adverse effect is GI upset (eg, vomiting, diarrhea, inappetence, weight loss), which is often temporary. If GI upset occurs, medication can be discontinued for 48 to 72 hours before therapy is restarted. Uncommon to rare adverse effects include gingival hyperplasia, liver enzyme activity elevations, and opportunistic infections.3 Rare opportunistic infections include toxoplasmosis and systemic or opportunistic fungal infections.3 These patients should be kept indoors, not be allowed to hunt rodents, be fed a cooked or commercial diet, and be FIV and FeLV negative4; however, in otherwise healthy FIV-positive cats, extra-label use of modified cyclosporine can be considered to reduce chronic corticosteroid requirements. Immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G serology for Toxoplasma gondii can be performed prior to initiation of modified cyclosporine. Patients with negative serology are more likely to develop clinical signs if exposed to T gondii while receiving modified cyclosporine.

The starting dosage for modified cyclosporine is 7 mg/kg PO every 24 hours for 4 to 8 weeks or until maximum clinical benefit is observed, after which the frequency can be tapered. For cats with mild clinical signs, administration can be decreased to every 48 hours, tapered to 2 to 3 times per week after signs are managed for 1 to 2 months.5 For cats with severe clinical signs, the author recommends decreasing the frequency more gradually by dropping 1 day per week each month until signs start to return.

The modified cyclosporine oral solution is a liquid. Canine veterinary-modified cyclosporine capsules can be used extra label in cats that do not tolerate liquid medications.7

Oclacitinib

Oclacitinib is not FDA-approved in cats, and dosages differ compared with dogs. Oclacitinib use can be considered as last-line therapy in cats that have not been responsive to other treatments or in cases in which corticosteroids are undesirable (eg, patient with diabetes). GI adverse effects are uncommon, and leukopenia, anemia, increased ALT, and increased renal values are rare.3,8,9 When effective, clinical benefit is typically seen within 1 to 2 weeks.

Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy

Immunoglobulin E testing (serum or skin) and immunotherapy are recommended for most cats with FASS that lasts >4 to 6 months per year. Immunotherapy injections are generally well tolerated, with 45% to 70% of cats showing improvement (eg, reduced clinical signs, reduced medication requirements, both) after ≈1 to 2 years.3,10-13 When effective, immunotherapy should be continued long-term or lifelong, but decreasing injection frequency over time may be possible. Adverse effects are rare, with increased pruritus being most common.

Antihistamines

Hydroxyzine and chlorpheniramine are rarely effective as sole therapies, likely because histamine has a limited role in FASS3,14,15; however, these drugs are unlikely to cause adverse effects and can be used adjunctively in patients with FASS.

Secondary Bacterial Pyoderma

Cats with FASS can develop bacterial pyoderma on eosinophilic granuloma complex lesions, on miliary dermatitis lesions, and in areas of self-induced excoriation or mutilation. Bacterial skin infections can increase pruritus and make FASS therapy appear less effective. Examination of skin impression smears or acetate tape cytologic specimens to assess for bacterial infection is recommended for all patients with lesions.

When possible, topical therapy with chlorhexidine or a combination topical antibiotic/corticosteroid product should be used. Widespread superficial pyoderma not amenable to topical therapy or deep pyoderma requires systemic antibiotics. First-line choices include amoxicillin/clavulanate, cephalexin, and clindamycin. Cefovecin (an injectable, third-generation cephalosporin) is not recommended as a first-line therapy due to concerns that increased third-generation cephalosporin use may increase risk for bacterial resistance.16

Pet Owner Communication

FASS is not curable but can be managed. Avoidance techniques (eg, increasing allergen filtration in the home, not letting the cat outdoors) may decrease clinical signs but are unlikely to lead to complete resolution.

Pet owners should be informed early during treatment that systemic medications, topical therapy, and/or lifelong immunotherapy may be required and that even cats with well-controlled disease can have 1 to 2 flares per year, which may require a temporary increase in or initiation of medical therapy.

Spectrum of Care Considerations

Allergic skin disease in cats can be a financial burden during diagnosis (eg, ectoparasite control trial, dermatophyte test media, prescription food trial) and treatment (eg, ectoparasite control, prescription diet, modified cyclosporine, oclacitinib). Early communication with the owner can help set realistic expectations for cost of ongoing care and multiple modalities of therapy to be performed in the home.

Pet owners want to understand the value of the care their pet is receiving. Not explaining the benefits of services can result in owners questioning clinicians’ motives. Clarification may improve owner retention and compliance. Better understand the Importance of Discussing Costs With Pet Owners.

In patients with a component of environmental FASS that require year-round therapy, oral corticosteroids are the least costly option, followed by modified cyclosporine (especially in patients that require therapy every 48-72 hours) and oclacitinib. Allergen-specific immunotherapy has significant initial costs (ie, testing, year-round immunotherapy), but long-term costs may decrease due to reduced need for corticosteroid and noncorticosteroid immunomodulators and monitoring blood work. Oral corticosteroids are likely the most cost-effective option in patients with clinical signs that last <4 to 6 months per year and are generally well tolerated in cats.

Potential adverse effects and individual patient needs must also be considered when selecting a treatment regimen.

Barriers to Care

Finances are a common barrier to care, and the long-term costs associated with allergic disease can add up quickly. Pet owners can also face emotional and physical barriers that should not be overlooked in care discussions. For instance, an owner caring for an elderly family member may feel overwhelmed at the recommended amount of monitoring, medication, and repeat visits needed for their cat; an owner without reliable transportation is likely to have limited ability to bring their cat back for follow-up care; and an owner with a physical or mental disability may have trouble administering treatment to their cat in the home.

When discussing diagnostic and treatment options, try these tips to better understand the owner’s concerns and any barriers they may be facing.

Use open-ended questions, like “How would you feel about doing an elimination diet trial at home?” or “What concerns do you have about giving oral medications?”

Be realistic about goals and expectations, which may be different for each owner. Try asking “What are your biggest concerns about your pet’s medical condition?” or “Are you worried that bringing your pet back for follow up visits will be stressful? If so, let’s talk about that.”

Read more about how to navigate barriers to care.