Exercise Intolerance & Chronic Cough in a Geriatric Dog

Cécile Clercx, DVM, PhD, DECVIM-CA, University of Liège

Elodie Roels, DVM, MSc

Ernest, a 10-year-old, 9.8-kg neutered West Highland white terrier, was presented for dyspnea and cyanosis that was preceded by 3 months of cough and exercise intolerance.

History

Ernest’s nonproductive cough sounded harsh, occurred at a frequency of 5 to 10 times per day, and appeared induced by handling and excitement. Both cough and exercise intolerance gradually worsened. Dyspnea and cyanosis had appeared over the past 3 weeks in association with stressful situations or during any kind of exercise. Treatment with furosemide (2 mg/kg PO once a day for 3 days)did not improve signs.

Related Article: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Examination

Ernest was tachypneic and displayed a severe expiratory dyspnea with a pronounced expiratory abdominal push. Bilateral diffuse inspiratory crackles were noted on thoracic auscultation. Buccal mucosal membranes were cyanotic. Heart rate, cardiac auscultation, and rectal temperature were within limits. Body condition score was 6/9. Before further investigation, the patient received an injection of butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg IM), and flow-by oxygen was administered.

Diagnostic Results

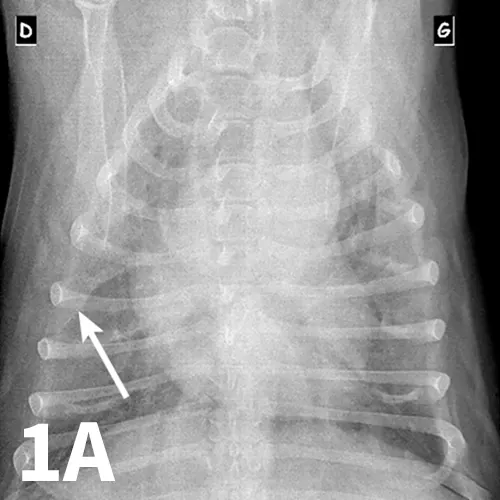

Ventrodorsal (A) and left and right lateral (B, C) thoracic radiographs of a 10-year-old West Highland white terrier showing a redundant tracheal membrane (1B, arrowhead; 1C, arrowhead), a severe generalized bronchointerstitial pattern, and a pleural fissure line (1A, arrow) between right pulmonary lobes.

Serum chemistry panel and CBC results were within range except for alkaline phosphatase (280 IU/L; range, 27-74) and hematocrit (57%; range, 37%-55%). Thoracic radiographs showed a severe bronchointerstitial pattern, right cardiomegaly, and prominent pulmonary artery trunk (Figure 1).

Echocardiography revealed severe arterial pulmonary hypertension estimated at 67 mm Hg in systole (range, <20) based on the peak velocity of the tricuspid regurgitant flow (Vmax TR 3.95 m/s; range, <2.9); severe right ventricular hypertrophy and septal flattening were also subjectively assessed. Arterial blood gas analysis indicated severe hypoxemia (pO2 47 mm Hg; range, 80-100) and hypocapnia (pCO2 27 mm Hg; range, 35-45).

A fecal Baermann analysis was negative.

Related Article: Acute Respiratory Distress: The Blue Patient

ASK YOURSELF

What is the clinical presentation of canine idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CIPF)?

Are bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) useful in the diagnosis of CIPF?

How is a diagnosis of CIPF confirmed?

What is the treatment for CIPF?

Diagnosis

Suspicion of canine idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CIPF) with severe secondary pulmonary hypertension.

Treatment

Ernest was hospitalized in an oxygen cage for 3 days and treatment with sildenafil (2.5 mg/kg PO twice a day) was initiated, which led to significant improvement in the dog’s clinical condition (progressive disappearance of the dyspnea and pink color of the mucous membranes). Ernest was discharged at day 5 after a progressive oxygen withdrawal, which was well-tolerated.

Related Article: Syncope in Small Breed Dogs

Outcome

At recheck evaluation 7 days later, Ernest was clinically improved with resolution of both dyspnea and cyanosis. Exercise was limited to two 15-minute walks per day, which were well-tolerated.

Cough was still present but did not impact his quality of life. Pulmonary crackles were still heard. Treatment was continued without adjustments. After 6 months of treatment, exercise tolerance had improved (three 30-minute walks per day, well-tolerated) and cough was present only occasionally. On echocardiography, subjective parameters of pulmonary hypertension were improved (absence of septal flattening), but the absence of a tricuspid regurgitant flow at this time precluded the objective assessment of pulmonary artery pressures. Blood gas analysis was not available (poor patient compliance).

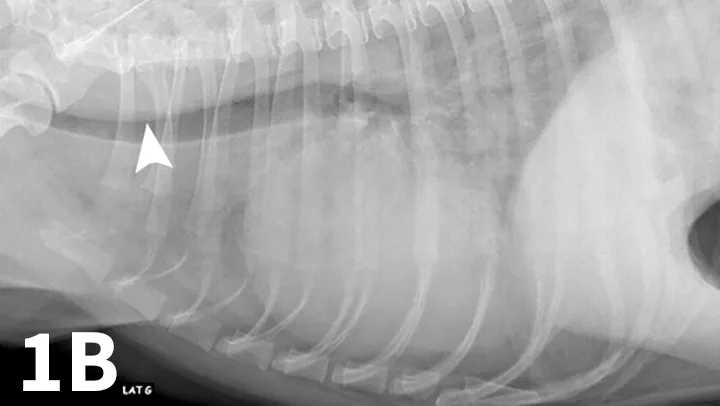

After 1 year of treatment, signs of CIPF and pulmonary hypertension were still under control. Lung crackles were still present on thoracic auscultation. A thoracic computerized tomography scan was performed under sedation to assess the distribution of lung parenchymal lesions (Figure 2). Lesions observed were compatible with those described in CIPF.1,2 Arterial blood gas analysis was performed under sedation and showed a pO2 of 51 mm Hg and a pCO2 of 41 mm Hg. The low arterial pO2 value is likely secondary to the severe underlying parenchymal lung disease and may have been compounded by the influence of sedation on the ventilation pattern (reduction in amplitude of respiratory movements).

Ernest was still alive 18 months after the initial workup. However, because of the cardiopulmonary debilitation and low likelihood of biopsy results influencing clinical management, antemortem biopsies were considered too invasive. The owner consented to confirmation of diagnosis by histopathology on a lung tissue biopsy sampled after death or euthanasia.

Transverse thoracic precontrast CT images (lung window) of the same patient at the level of the caudal lung lobes. Scans revealed an almost generalized ground-glass opacity (red asterisks), visible as an increase in overall opacity of the lung parenchyma without obscuration of the underlying vessels in the accessory and caudal lung lobes.

DID YOU ANSWER

CIPF is a progressive lung disease of unknown origin which usually affects middle-aged to older dogs of the West Highland white terrier breed.4 Classic signs are exercise intolerance and chronic cough in otherwise bright and alert dogs, but some dogs may be presented with history of syncope, cyanosis, respiratory difficulties, panting, or tachypnea. Bilateral inspiratory crackles are commonly noticed on lung auscultation and may be heard without a stethoscope when the dog is breathing with an open mouth. An abdominal breathing pattern consisting of an excessive expiratory push is commonly present. A right-sided systolic murmur can be heard in dogs with tricuspid regurgitation due to pulmonary hypertension, but because of the presence of crackles, adequate auscultation may be difficult.

Bronchoscopy and BAL fluid analysis provide useful information about lungs and airways. In dogs with CIPF, these complementary procedures often rule out infectious causes of disease and permit assessment of other respiratory abnormalities. In the present case, anesthetic risk was considered too high to perform a bronchoscopy and a BAL. Bronchoscopic findings in dogs with CIPF are not specific. Anomalies such as tracheal collapse, bronchial mucosal irregularity, increased amounts of bronchial mucus, bronchomalacia, or bronchiectasis may be observed, alone or in combination. Analysis of BAL fluid usually shows an increase in the total cell count because of increased numbers of macrophages and neutrophils. Bacterial growth is not commonly seen in CIPF.1

Impaired arterial blood oxygen in a geriatric West Highland white terrier with progressive clinical signs and crackles audible on thoracic auscultation can lead to a clinicial suspicion of CIPF. However, definitive diagnosis of CIPF is challenging and relies on histopathologic examination of lung tissue,3 although thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) may have a high specificity.1,2 HRCT findings include ground glass opacities, parenchymal bands, subpleural lines, subpleural interstitial thickening, peribronchovascular interstitial thickening, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing.1,2

There is currently no specific effective treatment for CIPF. Management mainly aims at reducing clinical signs on an individual basis and to alleviate comorbidities, such as pulmonary hypertension, when present. Oral corticosteroids might relieve cough in some dogs with secondary airway inflammation. Antitussives can be used if cough is irritating. Bronchodilators such as theophylline may be used to promote bronchodilation, enhance mucociliary clearance, and increase contractibility of the diaphragmatic muscle. When pulmonary hypertension is present, treatment with sildenafil may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life.

BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage, CIPF = canine idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, HRCT = high-resolution computed tomography