Echinococcus spp Tapeworms in Dogs & Cats

Emily Jenkins, PhD, DVM, BSc (Hons), Zoonotic Parasite Research Unit, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

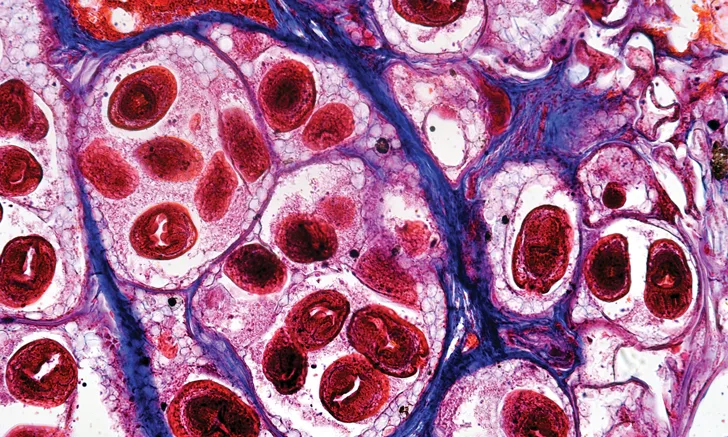

Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices in the liver of an intermediate host

Echinococcus spp are zoonotic cestodes that circulate among different carnivore and herbivore hosts (Table) around the world.1 Echinococcus granulosus is a complex of species and strains, the most important of which—from a public health perspective—circulate among livestock and dogs.1 The G8 and G10 genotypes of E granulosus, which are now known as E canadensis, circulate among cervids (ie, moose, caribou, elk, deer) and canids (ie, wolves, coyotes, dogs). In the northern hemisphere, another important zoonotic species, E multilocularis, primarily circulates among rodents and wild canids, with dogs and cats considered spillover hosts.

Dogs & Cats as Definitive Hosts

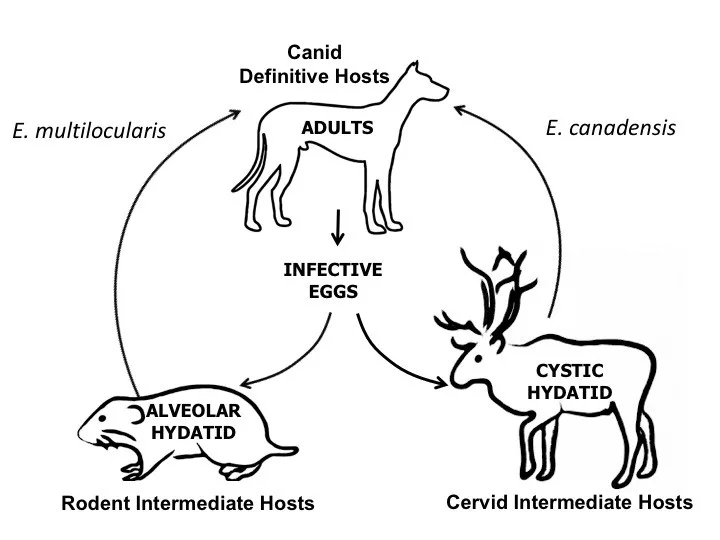

In North America, the life cycles of E canadensis and E multilocularis are primarily maintained in wildlife (Figure 1); however, when spillover occurs, dogs can serve as definitive hosts for both species, whereas cats can serve as definitive hosts only for E multilocularis, although prevalence and intensity are low in cats and infections may not be patent.1,2 Definitive hosts are subclinically infected with small adult cestodes 1 to 10 mm in length in the small intestine.3 Even if entire adult cestodes (Figure 2) are passed in feces, they are unlikely to be detected with the naked eye, unlike the segments of long, ribbon-like cestodes such as Dipylidium spp or Taenia spp. Eggs are taeniid type (Figure 3) and cannot be microscopically distinguished from those of nonzoonotic Taenia spp cestodes.

Figure 1 Life cycles of the 2 native species of Echinococcus in North America, which primarily circulate in wildlife. Intermediate hosts are infected by consuming eggs in the feces of definitive hosts, and definitive hosts are infected by consuming larval cestodes (alveolar or cystic hydatid) in the tissues of intermediate hosts.

Additional diagnostic challenges of Echinococcus spp infections on fecal flotation from definitive hosts include eggs not being shed during the prepatent period, intermittent shedding throughout patency, and eggs not always floating well in conventional salt and sugar flotation solutions.4 Because of these challenges, definitive diagnosis depends on molecular methods such as PCR5,6 or immunologic methods such as fecal coproantigen ELISA tests.7,8 However, these tests are not routinely available; therefore, there is great need for a sensitive and specific in-clinic test that can detect Echinococcus spp antigens or DNA in the feces of infected animals.

Echinococcus spp in the United States & Canada1

In Canada: Alberta, British Columbia, Labrador, Manitoba, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Ontario, Québec, Saskatchewan, Yukon Territory

In the United States: Alaska, at least 7 contiguous states (ie, California, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Minnesota, Maine)

|

In Canada: Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Ontario, Saskatchewan

In the United States: Alaska, north central United States (ie, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Wyoming)

| | Human disease | Cystic echinococcosis | Cystic echinococcosis | Alveolar echinococcosis | | Canine disease | None | None |

As definitive host: none

As intermediate host: alveolar echinococcosis

|

Treatment & Prevention of Adult Echinococcus spp in Dogs & Cats

In regions endemic for Echinococcus spp (see Table for endemic US and Canadian regions), clinicians should treat any dog or cat shedding taeniid-type eggs on fecal flotation with a cestocide labeled for Echinococcus spp such as praziquantel (5 mg/kg PO or 5.7 mg/kg IM),9 bearing in mind that Taenia spp are a more common source of such eggs. Clinicians in endemic regions should also prophylactically prescribe regular cestocidal treatment for any pet at risk for ingestion of infected intermediate hosts (eg, livestock, cervids, rodents).

The frequency of prophylactic treatment depends on the parasite species. The prepatent period for E granulosus and/or E canadensis in dogs is approximately 6 weeks,3 whereas the prepatent period for E multilocularis ranges from 26 to 36 days in dogs.9,10 Therefore, high-risk pets should be treated every 6 weeks in regions endemic for E granulosus and/or E canadensis and every 4 weeks in regions endemic for E multilocularis. Monthly treatment may be preferred to increase compliance, regardless of geographic location.

Related ArticlesSmall Animal Parasites That You Want to Forget (But Should Not)Common Tapeworm Proglottids of Dogs & CatsTop 5 GI Parasites in Companion Animal Practice

Dogs and cats are clinically unaffected when serving as definitive hosts for Echinococcus spp; however, treatment is important because of public health considerations. Eggs of E granulosus, E canadensis, and E multilocularis shed in pet feces are immediately infective and are environmentally resistant, with the ability to survive for months to years, and impervious to most chemicals (eg, formalin, ethanol, most commercial disinfectants). Eggs are inactivated by freezing at negative temperatures between -94°F and -112°F (-70°C to -80°C) for 3 to 7 days, by heating at temperatures greater than 140°F (60°C; ie, boiling, autoclaving, incineration), or by treating with 3.75% sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes in the absence of organic material.11

Dogs as Intermediate Hosts for E multilocularis

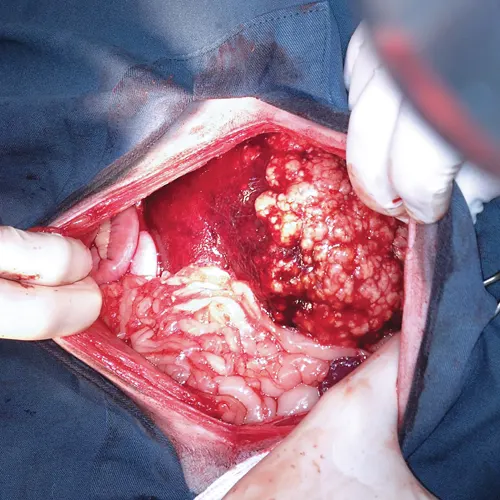

For E multilocularis, rarely, dogs can serve as aberrant intermediate hosts, in which the larval stages do not fully develop, or as true intermediate hosts, in which the larval stage fully develops and protoscolices are present (Table). The larval stage of E multilocularis takes the form of alveolar hydatid cysts that generally begin in the liver (Figure 4) and may spread throughout the abdominal cavity and, in progressive cases, throughout the body.12 This is known as alveolar echinococcosis, and canine alveolar echinococcosis, which is often fatal, has been increasingly diagnosed pre- or postmortem in endemic regions of Europe and North America and in regions of North America beyond the previously established western and eastern distributional limit of the parasite.12-15 In North America, this recent emergence may be because of the introduction of European strains of E multilocularis (likely via importation of infected dogs from Europe) that have been subsequently established in wild canids.13,16,17

Hepatic alveolar echinococcosis in exploratory laparotomy of a dog. All but one lobe of the liver was affected by raised white nodules, which are visible on the right side of the image. Photo courtesy of Audrey Tataryn, DVM

Dogs are presumably infected via consumption of eggs in the feces of wild canids in rural and remote areas; in urban areas, peri-urban green areas and off-leash parks may be contaminated.15,17 Rarely, cases of dogs with both adult cestodes in their intestines and alveolar echinococcosis have been described, which indicates that dogs could theoretically self-infect internally—as the eggs produced by adult cestodes are immediately infective—or externally via ingestion of eggs in their own feces.9

Breed and/or age predilections for canine alveolar echinococcosis cannot be inferred because few cases have been described. In 2 European studies of 23 and 11 cases, affected breeds included the shih tzu, dachshund, boxer, and Labrador retriever; in these studies, median age at time of diagnosis was 3.1 and 4.1 years, respectively.15,18 The most common clinical signs were abdominal distension, lethargy, and nonspecific GI signs.

Diagnosis of Alveolar Echinococcosis in Dogs

Radiography and ultrasonography may show suggestive space-occupying lesions, especially in the liver, that are similar in appearance to other cystic, neoplastic, or granulomatous lesions.18 Further imaging (ie, CT, MRI) may be more discriminatory and offer the option of clinical staging, as is similarly done in patients with neoplastic diseases.19 A serologic test is available in Europe but is only suggestive of alveolar echinococcosis, and false positives are possible.15,20

Definitive diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis in dogs relies on microscopic or molecular confirmation using fluid from abdominocentesis or material obtained by fine-needle aspiration, biopsy, or surgical excision. In humans, fine-needle aspiration of hydatid cysts poses risks for anaphylactic reactions and/or seeding of protoscolices (ie, larval cestodes) throughout the abdominal cavity.19 Cytology may yield a definitive diagnosis with detection of characteristic cestode calcareous corpuscles or, rarely, protoscolices.9,15,21 Alternatively, or in questionable cases, there are a variety of PCR assays that can be performed in any diagnostic or research laboratory to detect E multilocularis DNA.13,22-24 Molecular techniques—which require fresh, frozen, or ethanol-fixed material—also allow for further genetic characterization,25,26 which is needed to better understand the source of exposure for dogs and to determine whether there are parasite genetic differences in zoonotic potential and pathogenicity.27

Prognosis & Treatment for Alveolar Echinococcosis in Dogs

Prognosis for canine alveolar echinococcosis is poor if the infection is detected after it is well established, if abdominal effusion is present, and if treatment is delayed.15 Whereas complete surgical resection is ideal, long-term administration of benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole [10 mg/kg PO q24h]) has been reported to be as effective as a combination of debulking surgery (ie, incomplete resection) and long-term albendazole treatment.15 On initial diagnosis, dogs should also receive a cestocide labeled for adult Echinococcus spp infection (eg, praziquantel) for 2 consecutive days in case adult cestodes are concurrently present in the intestine.9 It is not known whether praziquantel will prevent alveolar echinococcosis in dogs; in humans, it has little demonstrable effect against established alveolar echinococcosis. Owners should be advised to consult their healthcare provider, as they may have been exposed to the same source of infection as the dog.9

Disease in Humans

Diseases caused by Echinococcus spp in humans, although uncommon, are potentially serious. In humans, eggs may develop into larval cestodes (ie, hydatid cysts) that initially serve as space-occupying lesions in the liver and lungs and can cause problems when they grow too large, rupture, and/or spread in the abdominal cavity or to distant organs.19 In North America, endemically acquired cases of human echinococcosis are rare and are generally caused by E canadensis, which has decreased pathogenicity as compared with E granulosus and E multilocularis.28

Domestically acquired human alveolar echinococcosis is exceedingly rare in North America but is potentially fatal; before modern early detection and aggressive treatment protocols, human alveolar echinococcosis was associated with case fatality rates of approximately 90%.29 Human echinococcosis has been linked to close association with dogs.30,31 For these reasons, owners of pets with definitively diagnosed intestinal Echinococcus spp infections should be advised to consult their healthcare provider.9

Global Relevance

Suggested Reading

Echinococcus spp cestodes are globally distributed and contribute significantly to human morbidity and mortality, as well as economic losses in livestock, especially in developing nations.34 Human echinococcosis is considered a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization (see ). Despite the term tropical, these parasites are well represented in the northern hemisphere, and some species (eg, E multilocularis) appear to be increasing in geographic range and prevalence in wildlife, pets, and humans.1,15,32,33 Veterinarians play a key role in the surveillance and control of these important tapeworms, which have both public and animal health significance.

Conclusion & Future Considerations

Surveillance in pets, wildlife, and humans is needed to detect and prevent geographic range expansion and global spread of Echinococcus species and strains. Clinicians play a key role in the detection and diagnosis of these parasites (see Global Relevance). Ideally, surveillance in animals can serve as early warnings of changes in parasite epidemiology and the risks posed to humans. The first detection of canine alveolar echinococcosis in Europe in the late 1980s9 was concurrent with an increase in the geographic range of the parasite in Europe32 and was followed by an increase in the human incidence of alveolar echinococcosis with a 20-year lag, as the incubation period in humans is 5 to 15 years.19,33

Increasing reports of canine alveolar echinococcosis in North America since 2009, in combination with detection of European strains of the parasite in both dogs and wildlife,13,16 may be an early warning of an emergence of human cases in North America in the next decade. Control of echinococcosis is possible, largely through veterinary interventions such as routine cestocide use in high-risk dogs in high-risk areas; risk assessment, screening, and treatment of translocated animals (both pets and wildlife); and client and public education.