Dry Eye in Dogs: When Good Glands Go Bad

Shelby Reinstein, DVM, MS, DACVO, VETgirl, Bucks County, Pennsylvania

Dry eye, or keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), is a common condition in dogs characterized by decreased tear production that most often results from idiopathic lacrimal gland inflammation with secondary glandular atrophy.1-3

Neurogenic KCS is caused by loss of parasympathetic innervation to the lacrimal gland and is less common than immune-mediated KCS. Neurogenic KCS occurs secondary to chronic otitis, peripheral neuropathies, idiopathic disease, and primary neurologic disease.<sup1,4 sup>

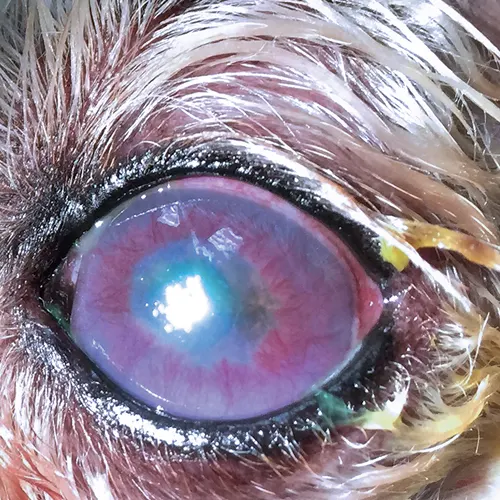

Decreased tear production results in corneal and conjunctival cellular hypoxia, debris accumulation, and bacterial overgrowth, causing inflammation of the ocular surface. Clinical signs include conjunctival hyperemia, squinting, and thick, sticky discharge.1-3 (See Figure 1)

KCS, indicated by mucopurulent ocular discharge, conjunctival swelling and hyperemia, and corneal pigmentation in an 8-year-old English bulldog

Common Causes of KCS

Congenital conditions (eg, congenital lacrimal aplasia)13

Infectious diseases (eg, canine distemper virus)14

Metabolic conditions (eg, diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism)1,2

Temporary or permanent drug toxicity (eg, from sulfasalazine, trimethoprim sulfa)15,16

Temporary drug side effects (eg, from atropine, general anesthesia)17-19

Trauma (eg, blunt trauma, radiation treatment)20

Clinical Signs of KCS1,2,4

Acute (see Figure 2)

This case of acute KCS in a 6-year-old Cavalier King Charles spaniel is indicated by the diffusely edematous and densely vascularized cornea and the lackluster corneal reflection. The eye has been stained with fluorescein and rinsed to remove discharge and debris.

Diagnosis

KCS should be suspected in all patients with clinical signs, especially in those with breed predisposition, including Cavalier King Charles spaniel, cocker spaniel, English bulldog, pug, shih tzu, West Highland white terrier, and Lhasa apso. Any patient with ocular surface inflammation, discharge, or corneal opacification should undergo the Schirmer tear test (STT), which quantifies the aqueous component of the tear film. Perform the test by placing the tear strip in the ventral conjunctival fornix, approximately midway between the medial and lateral canthi. Take care not to handle the tear strip excessively because oils present on fingers may affect the absorption dynamics.1,5,6 Leave the strip in place for 1 minute, remove it, and immediately record the measurement. (See Figure 3 & Table 1.)

STT results for a 10-year-old Chihuahua showing neurogenic KCS with abnormal results only in the left eye

STT Interpretation1

Once KCS is confirmed by STT results, thoroughly evaluate the patient’s ocular and systemic health to rule out underlying conditions such as hypothyroidism. A detailed eye examination, including fluorescein staining, should also be performed.

Neurogenic KCS most often occurs unilaterally, with ipsilateral nasal crusting a common supportive clinical finding.4 (See Figure 4.)

This case of neurogenic KCS in a 10-year-old Chihuahua is indicated by severe mucopurulent discharge, conjunctival hyperemia, corneal pigmentation, vascularization, and fibrosis in the left eye, whereas the right eye is normal. Note the ipsilateral nasal planum crusting, a common finding in the neurogenic form of KCS.

Treatment

KCS is managed medically, often with a combination of agents. (See Table 2.) Refractory cases may require alternative treatments, such as parotid duct transposition or eyelid surgery, by an ophthalmologist. Treatment regimens require periodic adjustments based on serial eye examinations and STT measurements. Lifelong treatment is usually necessary.1

Common Medications for Treating KCS

Immunomodulating agents

Cyclosporine (ointment or drops)

Tacrolimus (ointment or drops)

Cholinergic agents

Pilocarpine (topical or oral)

| | Tear replacements* |

Optixcare, Optixcare Plus

i-drop Vet Gel

GenTeal Severe Relief Gel

| | Antibiotics |

Neomycin – Polymyxin B –

Bacitracin ointment

Neomycin – Polymyxin B –

Gramicidin drops

Tobramycin

Gentamicin

Ciprofloxacin

Ofloxacin

| | Anti-inflammatories |

Neomycin – Polymyxin B –

Bacitracin + Hydrocortisone

Neomycin – Polymyxin B –

Dexamethasone ointment or drops

Gentocin sulfate + Betamethasone

|

*Author’s preferences

Tear Stimulants

Immunomodulating agents (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus), which reduce glandular inflammation and improve tear secretion, are most commonly used to treat KCS. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are used q8-12h initially; 30 to 45 days are required for full response. In dogs that respond well to initial therapy and achieve STT values >20 mm wetting/minute, treatment may be decreased to q24h or q12h for long-term maintenance. Tear-stimulant therapy is usually lifelong.1,7-11

Goals of Tear Stimulant Therapy1,8-11

Decrease or eliminate ocular discharge

Eliminate squinting

Reduce redness

Reduce corneal vascularization

Reduce corneal pigmentation

Cholinergic Agents

Cholinergic agents are used to treat neurogenic KCS. Pilocarpine can be administered either topically (ie, as a 0.125% or 0.5% drop) or orally (ie, by adding a commercially available 1% or 2% ophthalmic solution to the patient’s food). Topical administration is often quite irritating. Oral administration is effective but may cause systemic side effects with inappropriate doses. Given the markedly narrow safety margin, the dose should be adjusted slowly and the client advised to monitor the patient closely for side effects.1,4,12

Tear Replacements

Many commercial tear replacement products are available to treat tear deficiencies. Veterinarian preference, product availability and cost, and the patient’s specific needs determine treatment choice. These medications play a crucial role in KCS management and should be combined with tear-stimulant therapy.

Antibiotics & Anti-Inflammatories

Secondary bacterial conjunctivitis is common in dogs with KCS because of reduced ocular debris removal and surface inflammation. Broad-spectrum topical antibiotics should be administered in the early stages of treatment, usually q6-8h.1 As tear levels improve and ocular surface inflammation subsides, administration frequency can be decreased and treatment eventually stopped.

Topical anti-inflammatories or anti-inflammatory and antibiotic combinations are useful in reducing ocular surface inflammation, improving comfort, and diminishing corneal opacities and vascularization.1

Conclusion

KCS is a common ocular condition in dogs that occurs more frequently in predisposed breeds and should always be suspected in patients with ocular irritation signs. Diagnosis is made with the STT. A thorough eye examination helps identify concurrent corneal disease (eg, ulceration). KCS is initially treated with multiple medications that improve tear secretion, provide surface lubrication, and reduce bacterial overgrowth and surface inflammation. Medications can be adjusted as tear production improves; however, therapy with tear stimulants is almost always lifelong.