Diagnosis, Treatment, & Prognosis of Prostatitis in Dogs

Michelle A. Kutzler, DVM, MBA, PhD, DACT*, Oregon State University

In the Literature

Lea C, Walker D, Blazquez CA, Zaghloul O, Tappin S, Kelly D. Prostatitis and prostatic abscessation in dogs: retrospective study of 82 cases. Aust Vet J. 2022;100(6):223-229. doi:10.1111/avj.13150

The Research …

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland that likely occurs following ascension of normal urethral bacteria into a hyperplastic prostate gland or hematogenous spread. Prostatitis is typically chronic but may occur acutely. Prostatic abscessation occurs secondary to acute prostatitis or infected prostatic cysts. Dogs with prostatitis or prostatic abscessation may be presented with hematuria, urethral discharge, dysuria, pollakiuria, caudal abdominal pain, tenesmus, pyrexia, hyporexia/anorexia, lethargy, and/or systemic inflammatory response syndrome/sepsis.

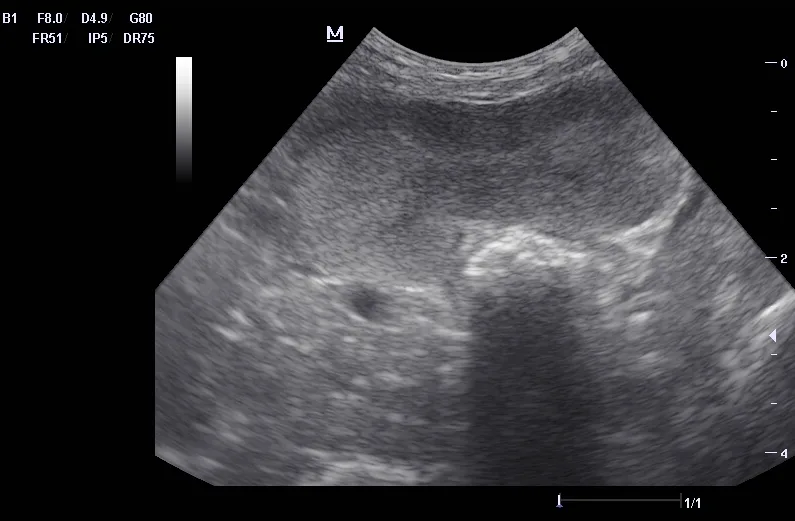

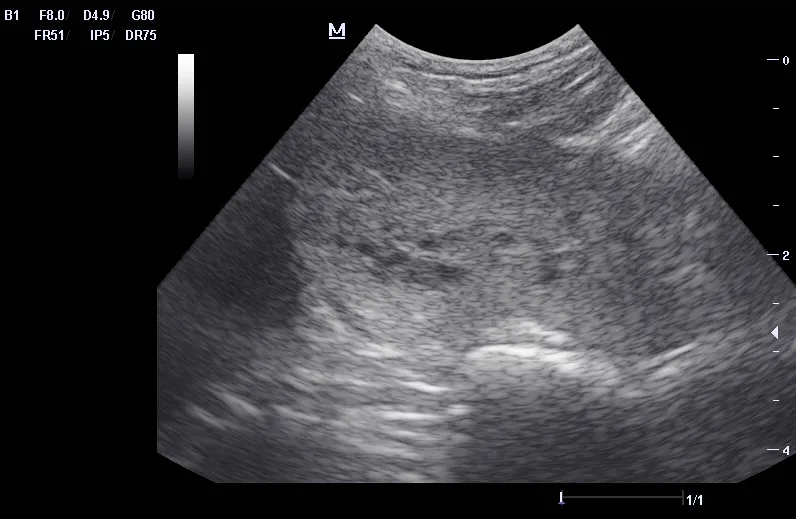

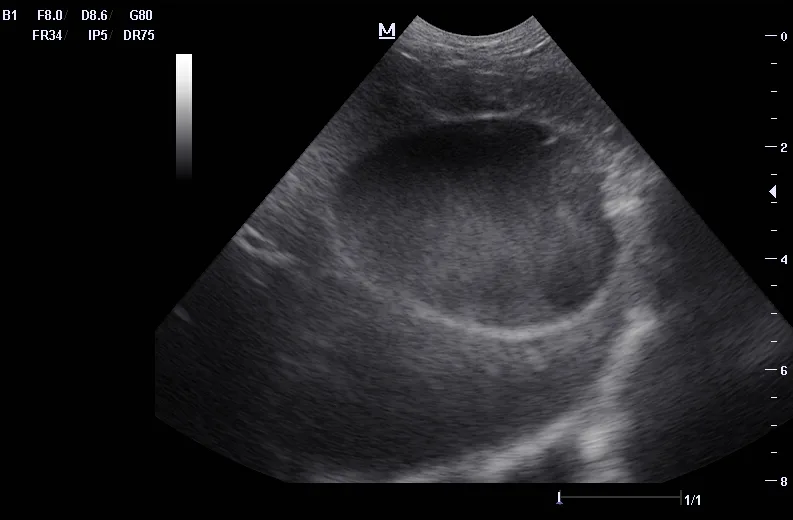

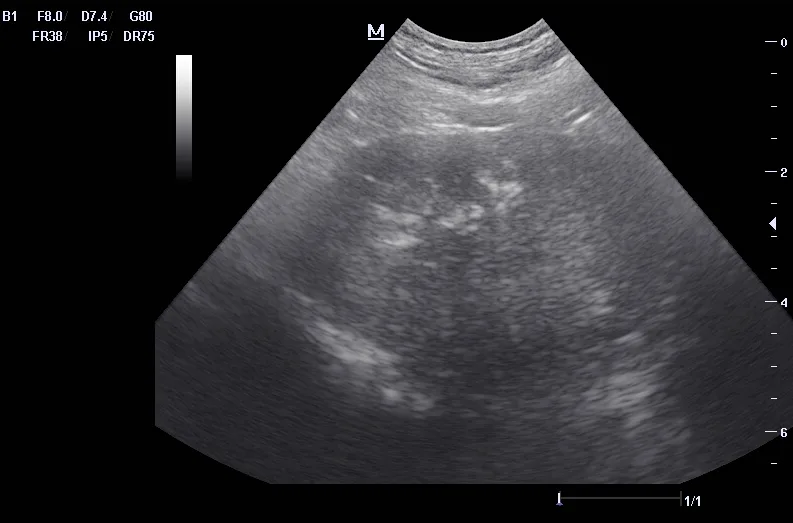

Ultrasound can be useful in evaluating the size, contour, and internal architecture of the prostate. A normal prostate appears homogeneous (Figure 1). The prostate becomes heteroechoic as a result of inflammation, hyperplasia, and neoplasia (Figure 2). The prostatic parenchyma can be focally or diffusely hypoechoic in cases of acute prostatitis or prostatic abscessation (Figure 3), as well as hyperechoic in cases of chronic prostatitis (Figure 4).

Normal prostate with a homogeneous appearance

Hyperplastic prostate with a heteroechoic appearance due to the presence of many small cysts

Prostatic abscess with a focal hypoechoic area

Prostate with chronic prostatitis. Several hyperechoic areas of mineralization can be seen.

This retrospective study included 82 dogs diagnosed with prostatitis. Acute prostatitis was diagnosed in 63% of cases, and chronic prostatitis was diagnosed in 37% of cases. Prostatic abscessation was diagnosed via ultrasound in 40% of cases.

Both prostatic and urine cultures were performed in 42 dogs with positive culture results; however, results of prostatic and urine cultures were concordant in only 50% of cases. Antimicrobial resistance was common, with 27% of cultures resistant to one antimicrobial and 49% resistant to ≥2 antimicrobials.

Abscesses were treated with antimicrobials alone, ultrasound-guided needle drainage, or surgical drainage. Antimicrobial treatment in conjunction with castration (medical or surgical) resulted in a good prognosis.

… The Takeaways

Key pearls to put into practice:

Prostatitis most commonly occurs in intact males ≥9 years of age but should also be considered in younger and/or neutered dogs. Although lower urinary tract signs are commonly observed, clinical signs may be absent, and prostatitis may be diagnosed incidentally.

Cytologic examination of prostatic fluid samples from semen collection, ultrasound-guided aspiration, or prostatic wash is necessary for diagnosing prostatitis. Fluoroquinolones are generally appropriate for treatment, as they exhibit antimicrobial efficacy against gram-negative bacteria (eg, Escherichia coli) and cross the blood–prostate barrier; however, bacterial culture with susceptibility testing should be performed, as the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in cases of prostatitis is high.

Small (ie, diameter, <10 mm) prostatic abscesses can be treated with castration (surgical or medical) and antimicrobials alone, with or without percutaneous needle drainage. This treatment is safe, has a relatively high success rate, and may be preferable to surgical intervention.

Medical castration with osaterone acetate, delmadinone acetate, or deslorelin acetate is less invasive and safer than surgical castration in systemically ill and potentially unstable patients. In addition, surgical castration during active prostatic infection can increase the likelihood of scirrhous spermatic cord formation.1

You are reading 2-Minute Takeaways, a research summary resource proudly presented by Clinician’s Brief. Clinician’s Brief does not conduct primary research.