Diagnosing Liver Disease

Nick Bexfield, BVetMed, PhD, DSAM, DECVIM-CA, FSB, MRCVS, University of Nottingham

Liver disease is relatively common in small animals, but the diagnosis can be a challenge.

Profile

The liver has tremendous functional and structural reserve, and a significant loss of normal hepatic tissue can occur with minimal or no clinical signs.1

Because of the liver’s central role in metabolism, it may be secondarily affected by a disease process elsewhere (eg, hyperadrenocorticism, sepsis, hypoxia).

Secondary hepatopathies often resolve when the underlying disease is appropriately treated; it is important to determine if an underlying disease process is present early.

History

The onset of clinical signs is often insidious and usually only occurs once the reserve capacity of the liver has been exceeded.

Clinical signs are often non-specific; most frequent signs include depression, lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, polyuria, and polydipsia.

The clinician should pay attention to subtle waxing and waning GI signs (eg, decreased appetite, vomiting, diarrhea).

Additional signs that may be suggestive of liver disease (although still not specific) include jaundice, ascites, and neurologic signs caused by hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

Clinical signs of HE are often intermittent and include behavioral changes, hypersalivation, head pressing, circling, ataxia, temporary blindness, seizures, and/or coma.

FIGURE 1 Jaundice in an English springer spaniel with liver disease.

Physical Examination

Findings are typically unremarkable.

A decrease in body condition score may be noted.

In dogs, liver size will be normal-to-enlarged with acute disease, normal-to-small with chronic disease.

In cats, liver size will be normal-to-enlarged in acute and chronic disease.

Palpable hepatomegaly may be appreciated in dogs and cats with an enlarged liver

Jaundice occurs in approximately 20% of dogs and 30%-40% of cats with hepatobiliary disease, and it often occurs late in the disease process (Figure 1).1

Ascites may be present; it is more commonly associated with chronic disease.

Related Article: Chronic Liver Disease

Laboratory Testing

Blood tests to assess liver enzymes and liver function are usually the simplest next steps in the investigation of patients with suspected liver disease.

Definitive diagnosis cannot be based on results of blood tests alone; these results should form part of the overall investigation.

Chemistry Panels

Liver enzyme activity should be measured in all patients with suspected liver disease, but these allow no evaluation of hepatic function.

In general, liver enzymes (Table) are sensitive indicators of liver disease or injury but are not specific.2

Non-specificity derives from the susceptibility of the liver to secondary or reactive disorders and the ability of certain hormones or drugs (eg, corticosteroids) to induce synthesis and release of some liver enzymes.

Table: Commonly Measured Liver Enzymes & Interpretation

Tests of Liver Function

Tests are generally non-specific, although bile acids and ammonia are more specific markers of hepatic function.

Albumin

Albumin is produced in the liver; hypoalbuminemia is only seen when there is >75% reduction in functional hepatic mass.1

Glucose

Hypoglycemia occurs most commonly in acute fulminant hepatic failure, in small-breed dogs with portosystemic shunts, or in end-stage liver failure.2

Cholesterol

Cholesterol can be normal, increased, or decreased in liver disease and is a relatively insensitive marker of liver function.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

BUN is decreased when there is >75% reduction in functional hepatic mass.1

It is also commonly decreased in animals with congenital portosystemic shunt (PSS).

Bilirubin

Hepatic hyperbilirubinemia is associated with impaired hepatic uptake, conjugation, or excretion into bile.

It occurs when severe intrahepatic cholestasis develops and when there is more than a 75% reduction in functional hepatic mass.1

Total bile acids

Baseline (fasting) and 2-hour postprandial samples should be collected.

Levels will be elevated in bile stasis, reduced hepatic function, and in animals with congenital or acquired PSS.

They should not be measured in patients with hyperbilirubinemia.

Ammonia

Hyperammonemia occurs with congenital or acquired PSS and when there is >75% reduction in functional hepatic mass.3

Clotting times

Elevated prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) are seen when there is more than a 75% reduction in functional hepatic mass.1

Related Article: Top 5 Liver Conditions in Dogs

Hematology

Mild non-regenerative normocytic normochromic anemia is frequently identified in these patients.

Microcytic and hypochromic anemia may be present in patients with congenital PSS.

Regenerative anemia may be present with GI bleeding.

Morphologic changes in erythrocytes, namely acanthocytes and/or target cells (ie, codocytes) may develop.

Thrombocytopenia may occur from platelet sequestration or increased destruction.

An inflammatory leukogram may be present with any inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic hepatic process.

Urinalysis

A low specific gravity (<1.025) is common in chronic liver disease and congenital PSS.

Bilirubinuria is found in animals with hyperbilirubinemia; it is nonspecific in dogs, but a specific indicator of liver disease in cats.

Urobilinogen is normally found in urine, but increased amounts are associated with hyperbilirubinemia.

Urate or ammonium biurate crystals may be seen in patients with hepatic disease—particularly congenital PSS.

Imaging

Diagnostic imaging is an important part of the investigation of an animal with suspected liver disease.

Imaging sometimes allows identification of a specific cause (eg, congenital PSS), but it typically just adds more to the overall clinical picture.

Imaging may also identify the presence of any extrahepatic condition.

Abdominal radiography can be used to assess liver size, position, and shape, and it can evaluate for the presence of additional abdominal pathology.

Radiography in the presence of ascites is generally unhelpful because the fluid obscures abdominal detail.

Venography (via injection of contrast media into a mesenteric vein) may be used to assess portal vein vasculature.

This is most useful for the identification of congenital PSS.

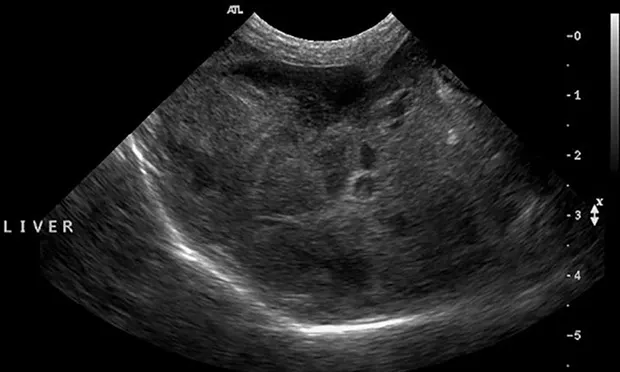

Ultrasonography is generally the preferred diagnostic imaging modality for evaluation of the liver, and it is particularly useful for mucoceles.

The normal liver has a homogenous echogenicity that is isoechoic to slightly hyperechoic to the renal cortex.

Changes in hepatic echogenicity occur in acute and chronic liver disease (Figure 2).

Ultrasonographic changes are usually not specific for a particular disease.

The liver can also appear ultrasonographically normal, even in severe disease.

Ultrasonography is useful for examination of the biliary system, including gallbladder size, contents, and wall thickness, as well as for the intra- and extra-hepatic bile ducts.

Doppler ultrasonography and scintigraphy are used for the identification of PSS.

FIGURE 2 Ultrasonographic image demonstrating a diffusely mottled and nodular appearing hepatic parenchyma.

Sampling Liver Tissue

Results of clinical pathology and diagnostic imaging typically do not provide a definitive diagnosis in patients with liver disease, except in patients with congenital PSS.

Obtaining liver tissue is the next step in the investigation of patients with liver disease.

Many methods are available and depend on clinician preference, equipment availability, technical skills, type of lesion present, location, and the systemic stability of the patient.

A minimum database to screen for hemostatic dysfunction includes a platelet count, PT and PTT, and a buccal mucosal bleeding time prior to sampling.

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology is minimally invasive, requires little equipment, and is relatively safe.

However, FNA has limited diagnostic accuracy and is generally only useful to diagnose hepatic vacuolation or diffuse tumors such as lymphoma.

Obtaining liver tissue using an ultrasound-guided automated or semiautomated cutting-type biopsy needle or during laparotomy or laparoscopy is acceptable.

Liver tissue should be submitted for histopathologic evaluation (Figure 3).

In addition to standard hematoxylin and eosin, a variety of additional stains can be used, such as Fouchet’s, Masson’s trichrome, periodic acid-Schiff, Perl’s Prussian Blue iron stain, reticulin, rubeanic acid, and rhodanine.

Unfixed liver tissue can also be submitted for quantitative copper analysis. Note that formalin-fixed tissue is not appropriate.

Cholecystocentesis (either percutaneously under ultrasound guidance or directly during laparoscopy or laparotomy) should be performed in patients with suspected biliary tract disease.

Animals should be monitored carefully for signs of hemorrhage for ≥12 hours after sampling liver tissue.

FIGURE 3 Histopathology sample obtained at laparotomy that demonstrates regenerative nodules (wide arrows) and fibrosis (thin arrows), both of which are indicative of cirrhosis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; 40× magnification.

Related Article: Top 5 Liver Conditions in Cats

Relative Cost

Relative cost for diagnosis including laboratory testing: $–$$

Relative cost for diagnosis including laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging: $$$–$$$$

Relative cost for diagnosis including laboratory testing, diagnostic imaging, and liver biopsy: $$$$–$$$$$

ALT = alanine aminotransferase, ALP = alkaline phosphatase, AST = aspartate aminotransferase, BUN = blood urea nitrogen, FNA = fine-needle aspiration, GGT = gamma-glutamyl transferase, PSS = porto-systemic shunt, PT = prothrombin time, PPT = partial thromboplastin time