Periodontal disease is common in companion animals.1,2 Treatment should start with a complete oral examination with the patient under general anesthesia and include intraoral imaging, dental charting, evaluation of periodontal attachment loss, and diagnosis of dental abnormalities, followed by a thorough dental cleaning (both above and below the gum line). Treatment of periodontal pockets and surgical extraction of severely diseased teeth are often necessary.

Recognizing and avoiding common complications that can result from dental treatments is important. Following are the top 5 complications that occur secondary to dental procedures according to the author.

1. Poor Gingival Flap Healing

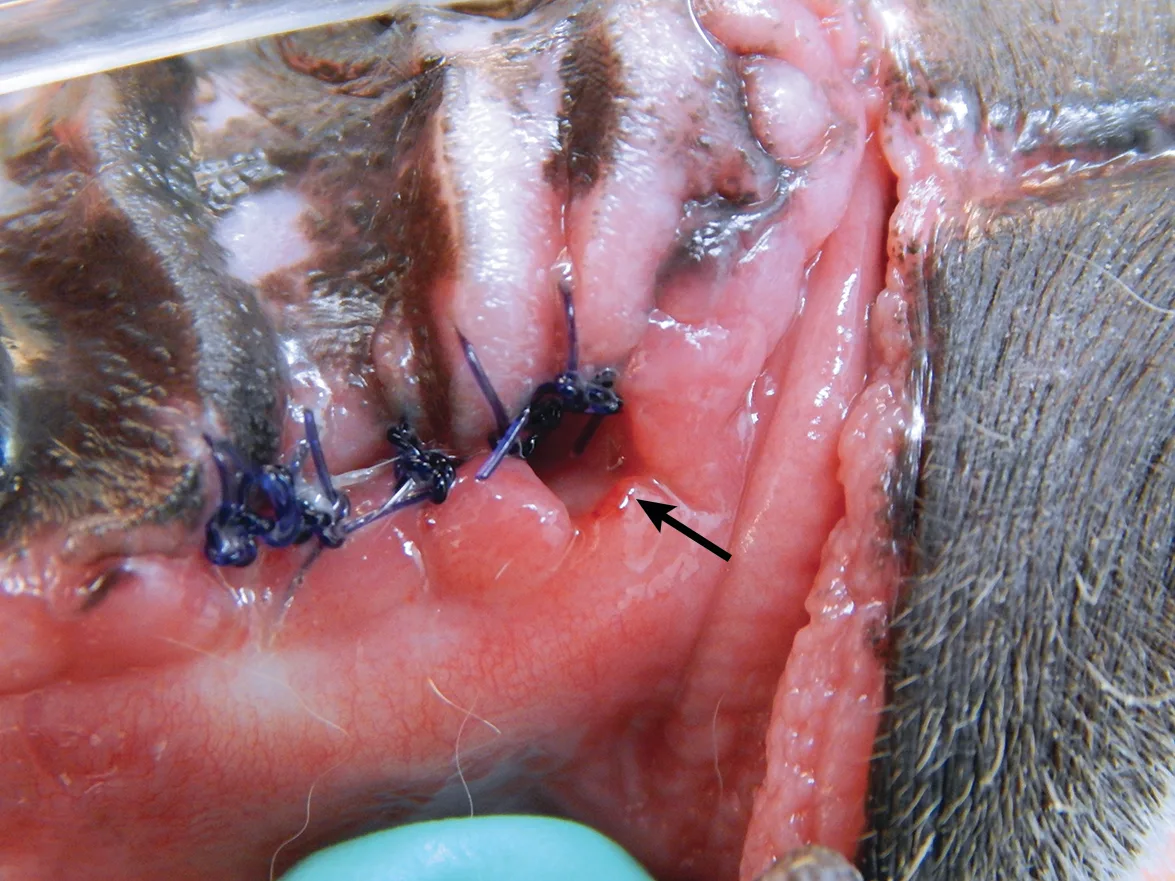

Most tooth extractions and many periodontal treatments require elevation of mucogingival flaps for appropriate removal of buccal alveolar bone. Gingival flap dehiscence (Figure 1) is the most common complication of dental extractions and often occurs with other types of maxillofacial surgery.3 Dehiscence is more common when gingival tissue is damaged by aggressive tissue handling during surgery or when a gingival flap is closed under tension.

(A) A dog with a large area of dehiscence associated with left maxillary canine tooth extraction; a large oronasal fistula is visible with yellow foreign material present in the nasal cavity (arrow). (B) A dog with a small area of dehiscence associated with left maxillary canine tooth extraction; an oronasal fistula is visible in the center of the extraction site closure (arrow).

Gingival tissue can be inadvertently damaged during extraction (Figure 2), most commonly as a result of clinician inexperience or inadequate training in proper surgical extraction techniques. Gingival tissue manipulation training should be a prerequisite for performing surgical dental extractions.

Wound dehiscence (arrow) caused by wound tension and iatrogenic tissue damage in a cat presented for surgical repair of the maxillary canine tooth extraction site

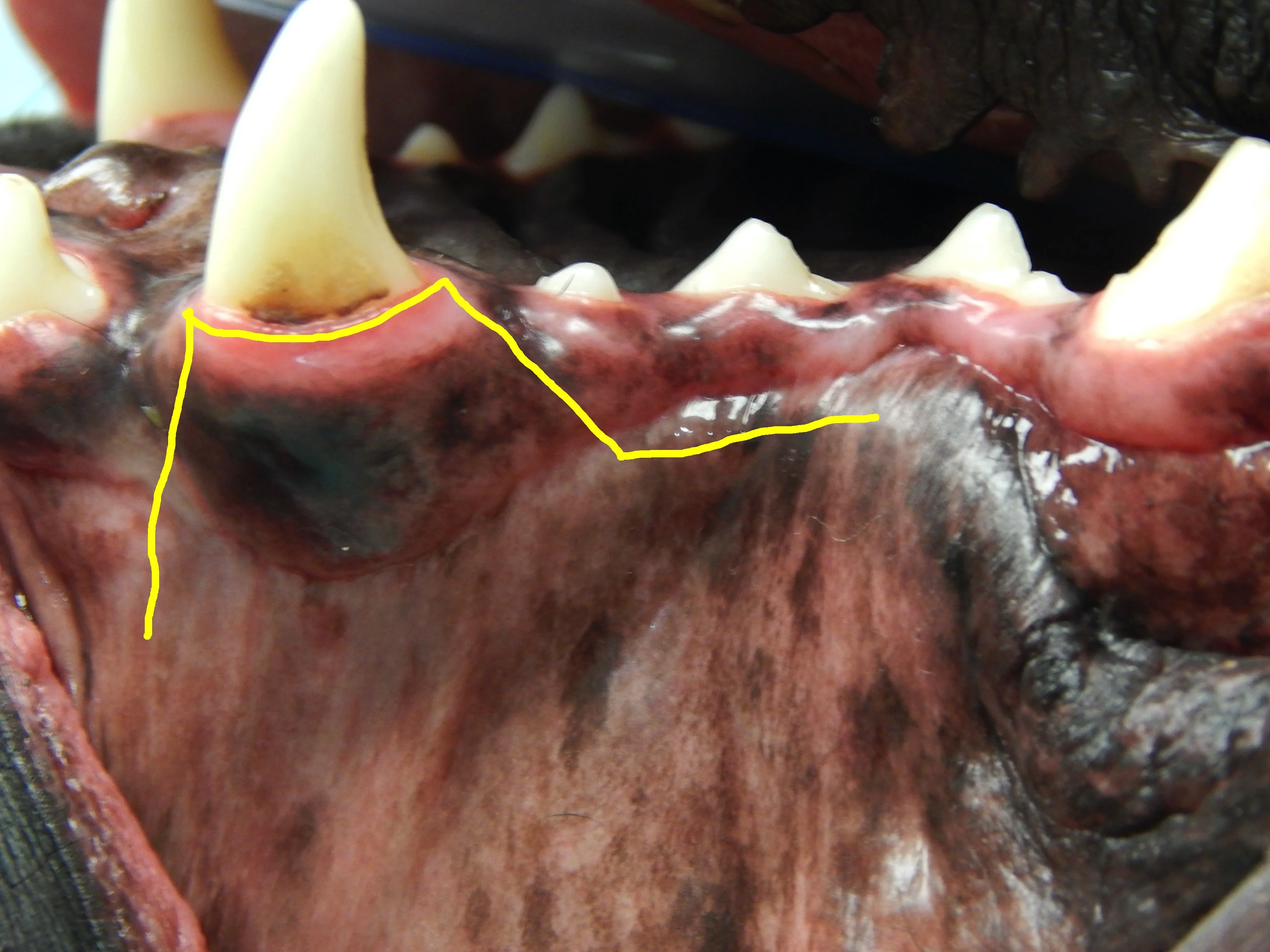

Closing a mucogingival flap under tension increases the risk for dehiscence,4 and understanding the options available for complete flap mobilization (eg, proper release of the periosteum, preplanning advancement flap design, releasing incision placement) is important when reducing tension on a flap. Damaged tissue should be removed prior to closure of the wound. Patients with severe periodontal disease can have significant loss of the buccal-attached gingiva and mucosa (Figure 3). Tissue that is lost, either due to pre-existing disease or surgical trauma, makes closure of a gingival flap more difficult.

Calculus accumulation and significant loss of the attached gingiva (arrows) of the left maxillary canine tooth. Gingival recession can make surgical closure more difficult and increase the potential for postoperative complications.

Releasing periosteal flap attachments (Figure 4; Video) and making strategic releasing incisions are the most effective methods of flap mobilization (Figure 5). A good working knowledge of these techniques can help facilitate flap closure without tension.

Curved iris scissors used to dissect and sharply cut the periosteum for mucogingival flap release

Creation of a mucogingival flap via a traditional diverging release (A) and a variation with the distal release turned to be parallel and 1 to 2 mm above the mucogingival line (B) can be used to make releasing incisions to raise a mucogingival pedicle flap and extract the right maxillary canine tooth.

2. Oronasal Fistula

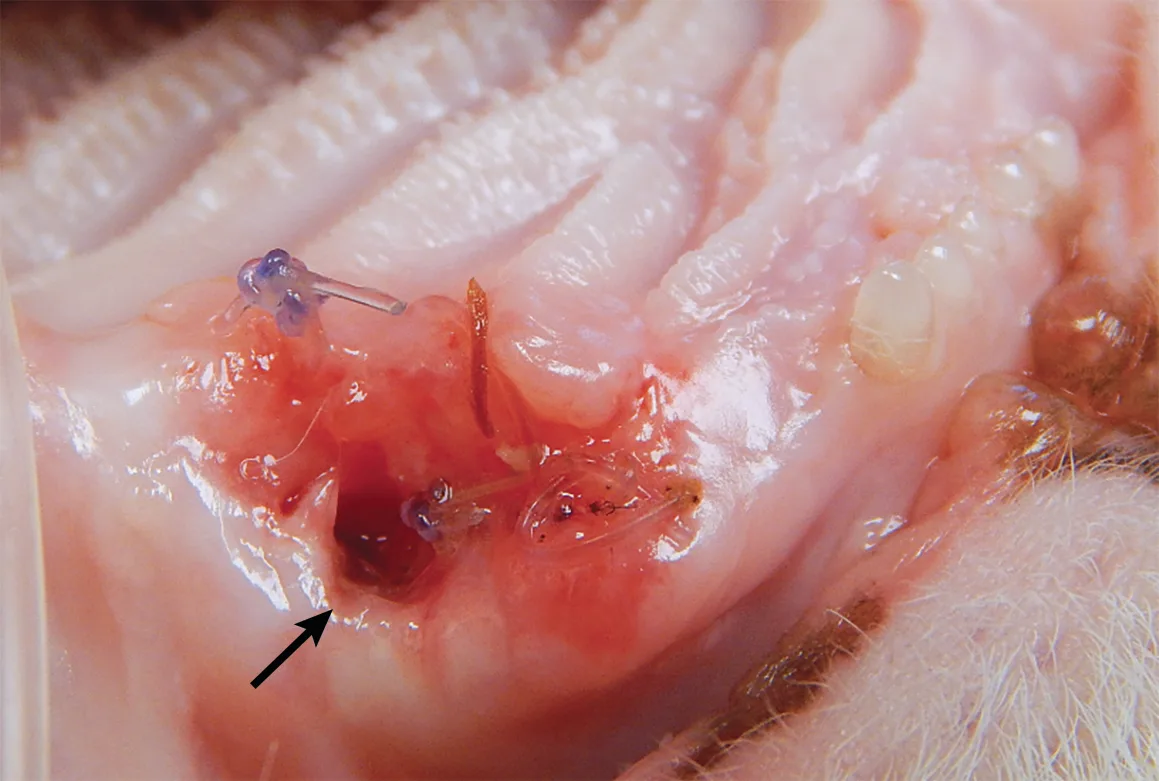

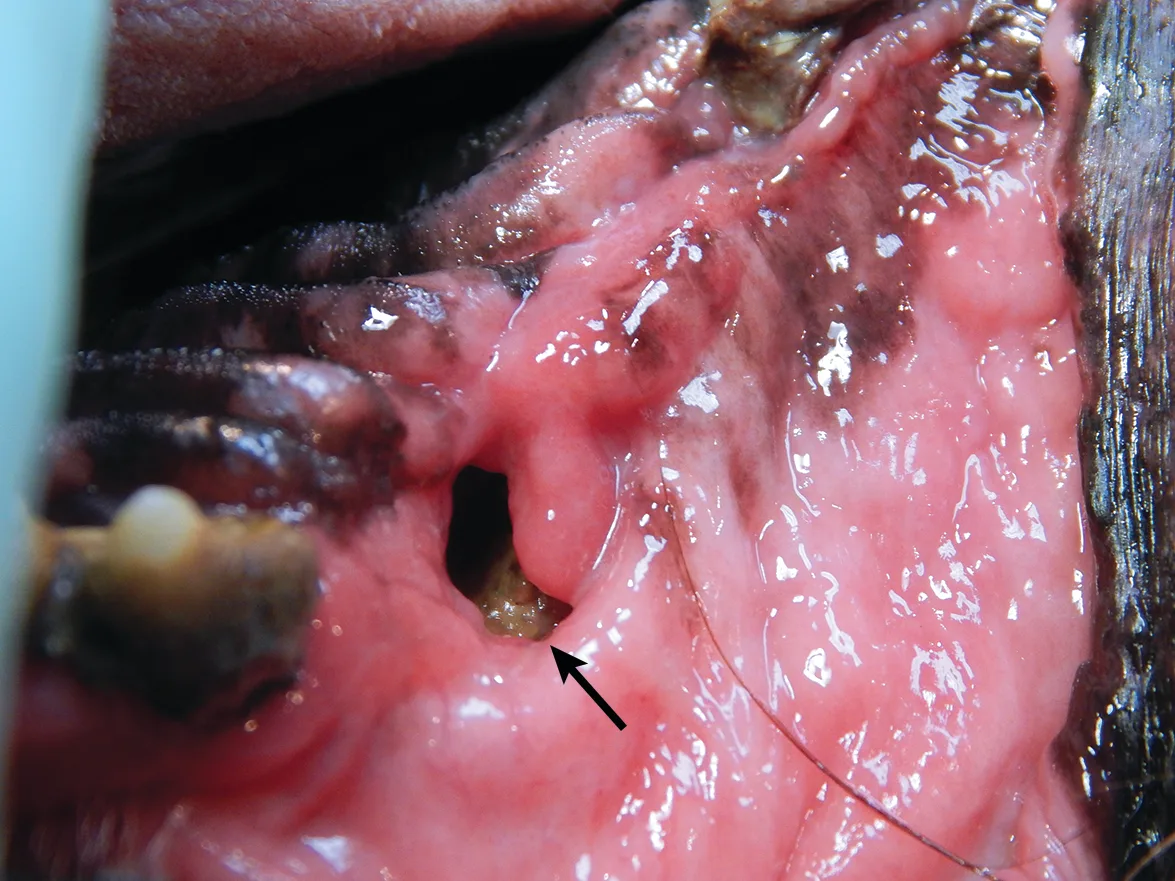

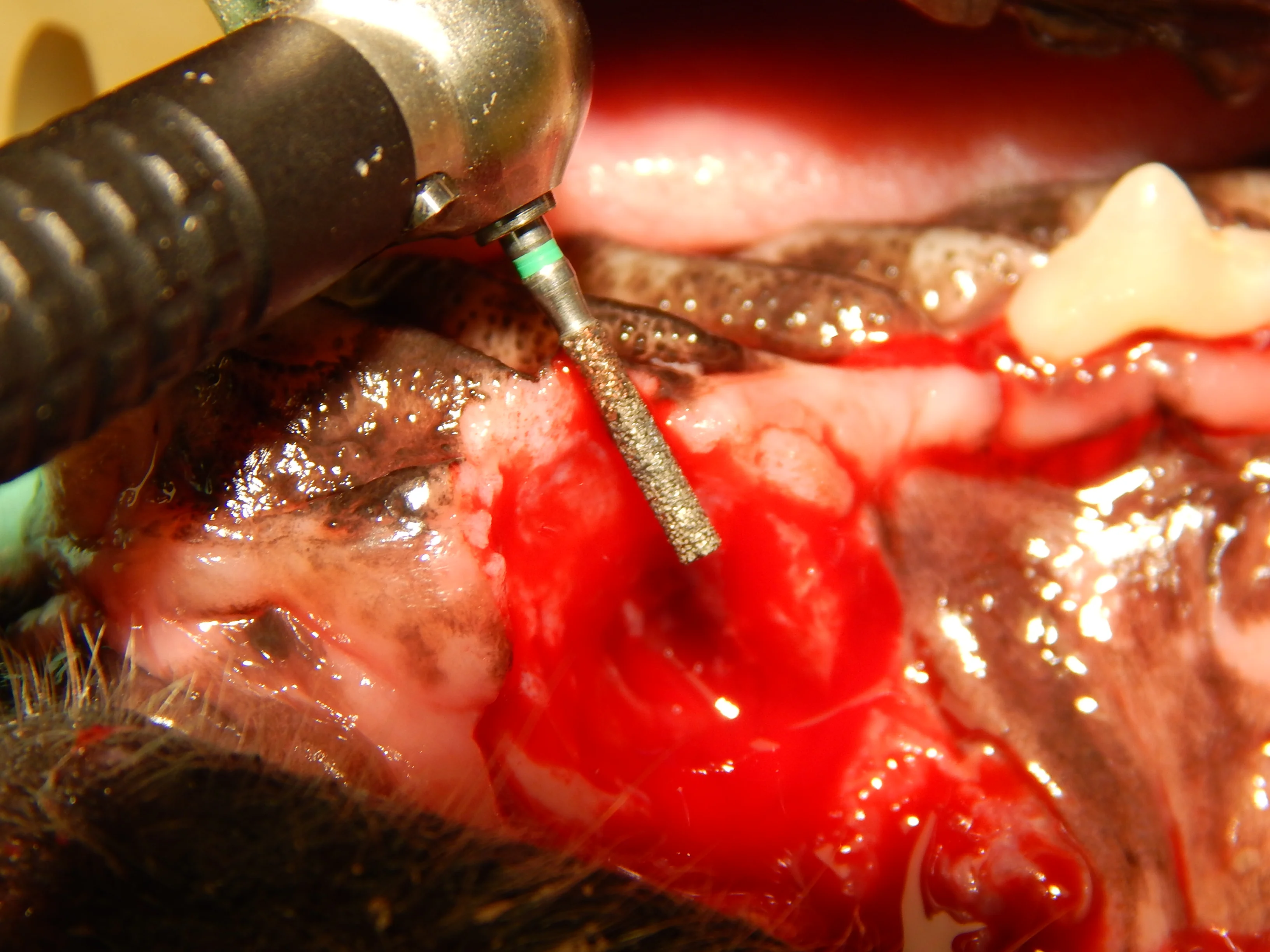

Oronasal fistulas may often be present prior to surgical extraction of maxillary teeth (Figures 6 and 7) but can also be a result of the surgical procedure. Although any maxillary tooth extraction can result in an oronasal fistula, it is most common following extraction of a maxillary canine tooth. Inadequate healing may lead to chronic oronasal fistulation (Figure 8). The quality of the tissue used to close the fistula and lack of wound tension are especially important in closure of oronasal fistulas. Development of a healthy recipient bed for the flap (Figure 9) and use of an Elizabethan collar to prevent self-trauma by the patient can also reduce flap failure.4

A dental probe used to demonstrate the presence of an oronasal fistula (arrow) affecting the right maxillary canine tooth

Appearance of the oronasal fistula in Figure 6 after surgical extraction of the right maxillary canine tooth. Purulent exudate (arrow) is visible in the nasal cavity through the oronasal fistula.

A chronic oronasal fistula (arrow) at the extraction site of the right maxillary canine tooth. Foreign material can be seen in the nasal cavity.

A coarse cylindrical diamond bur used to create a recipient bed (A). Removal of the epithelium allows improved healing of the sutured mucogingival flap (B).

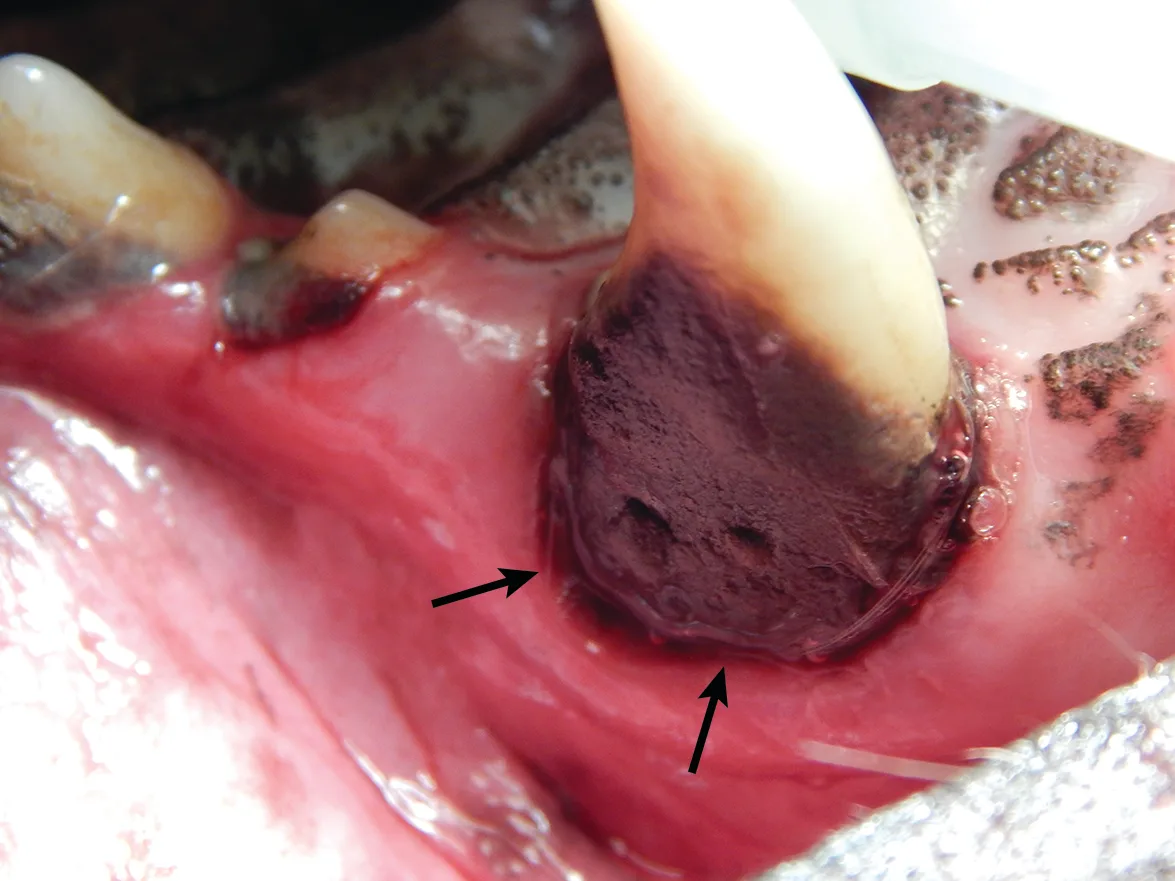

3. Jaw Fracture

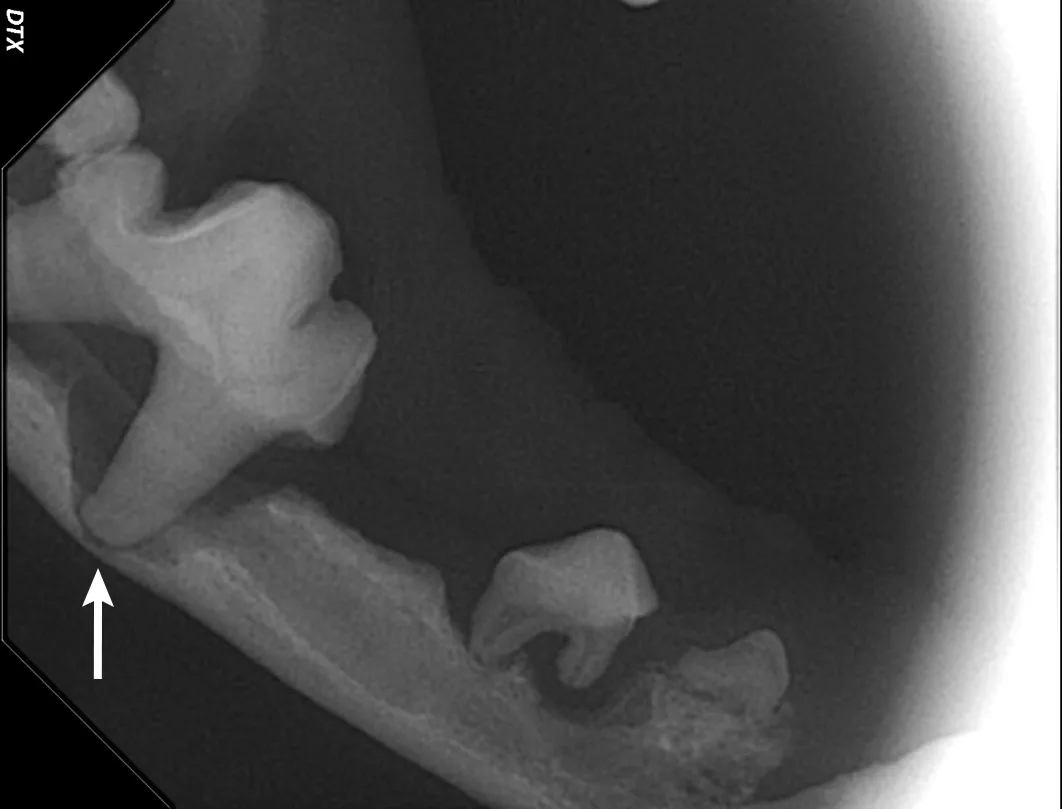

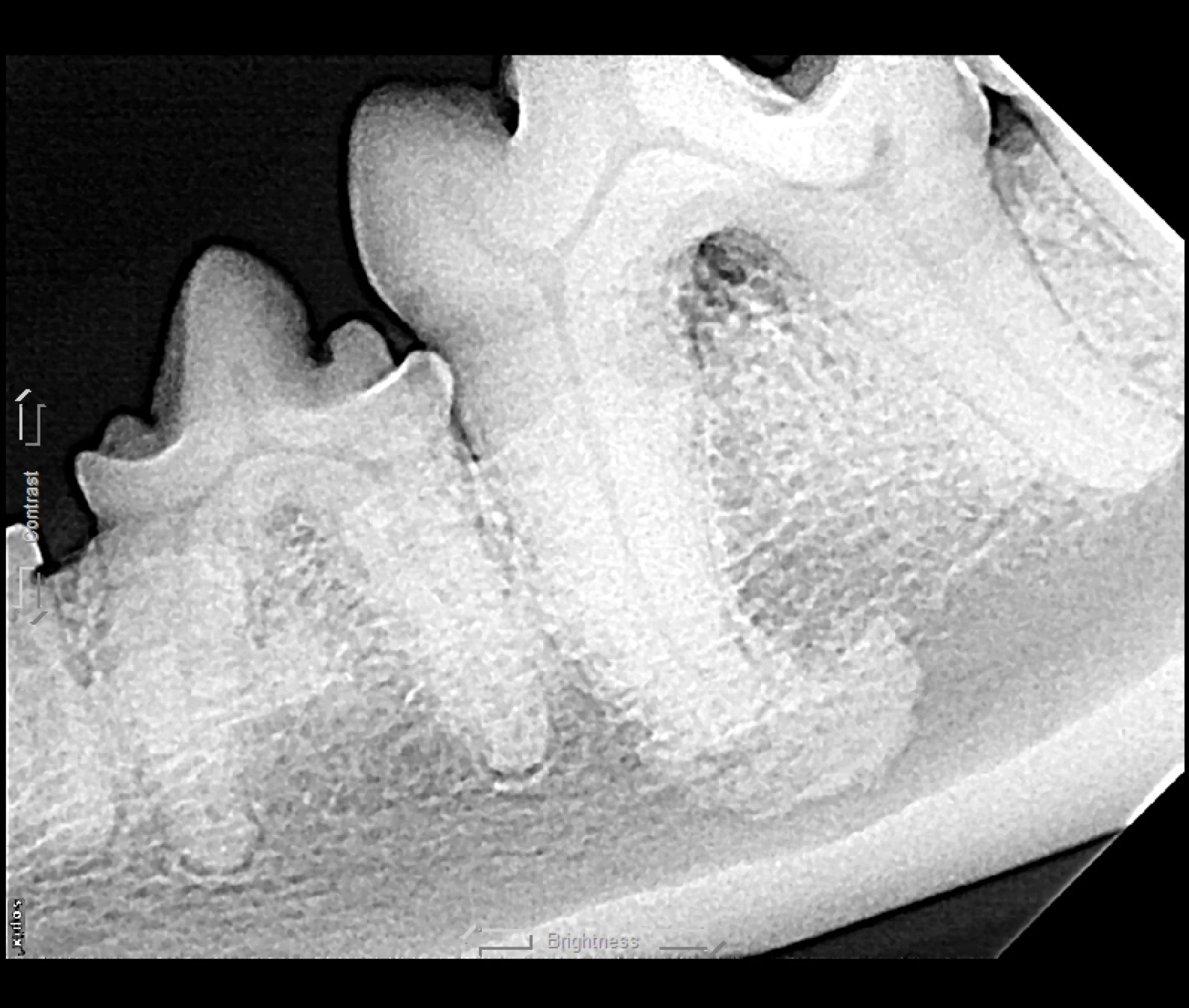

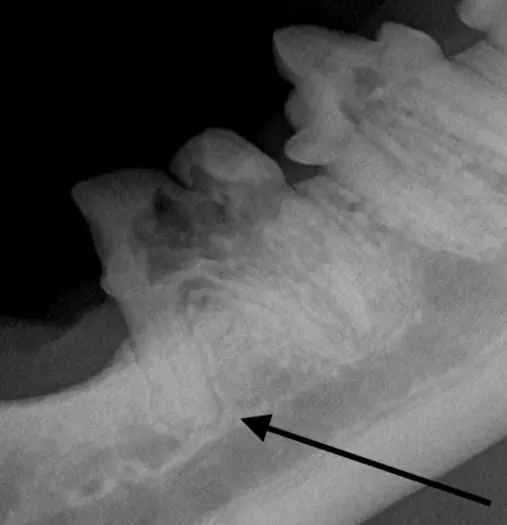

Iatrogenic fracture of the jaw can be a serious complication of surgical extractions and is most commonly associated with surgical extraction of mandibular canine teeth in dogs and cats and mandibular first molar teeth in dogs (Figure 10). These extractions can be difficult to perform, as the root apexes are often located in close proximity to the ventral cortex of the mandible, possibly leading to significant bone loss when severe disease is present and increasing the risk for iatrogenic fracture (Figure 11).

Pathologic fracture (arrow) secondary to severe periodontal disease of the right mandibular first molar tooth in a dog

Severe periodontal disease affecting the right mandibular first molar tooth in a dog. Careful extraction technique is necessary to extract the tooth without creating an iatrogenic fracture.

Preoperative intraoral radiographs are critical for assessing fracture risk, especially prior to surgical tooth extraction, and can be used to modify the procedure or refer a patient with high fracture risk to a board-certified veterinary dentist.

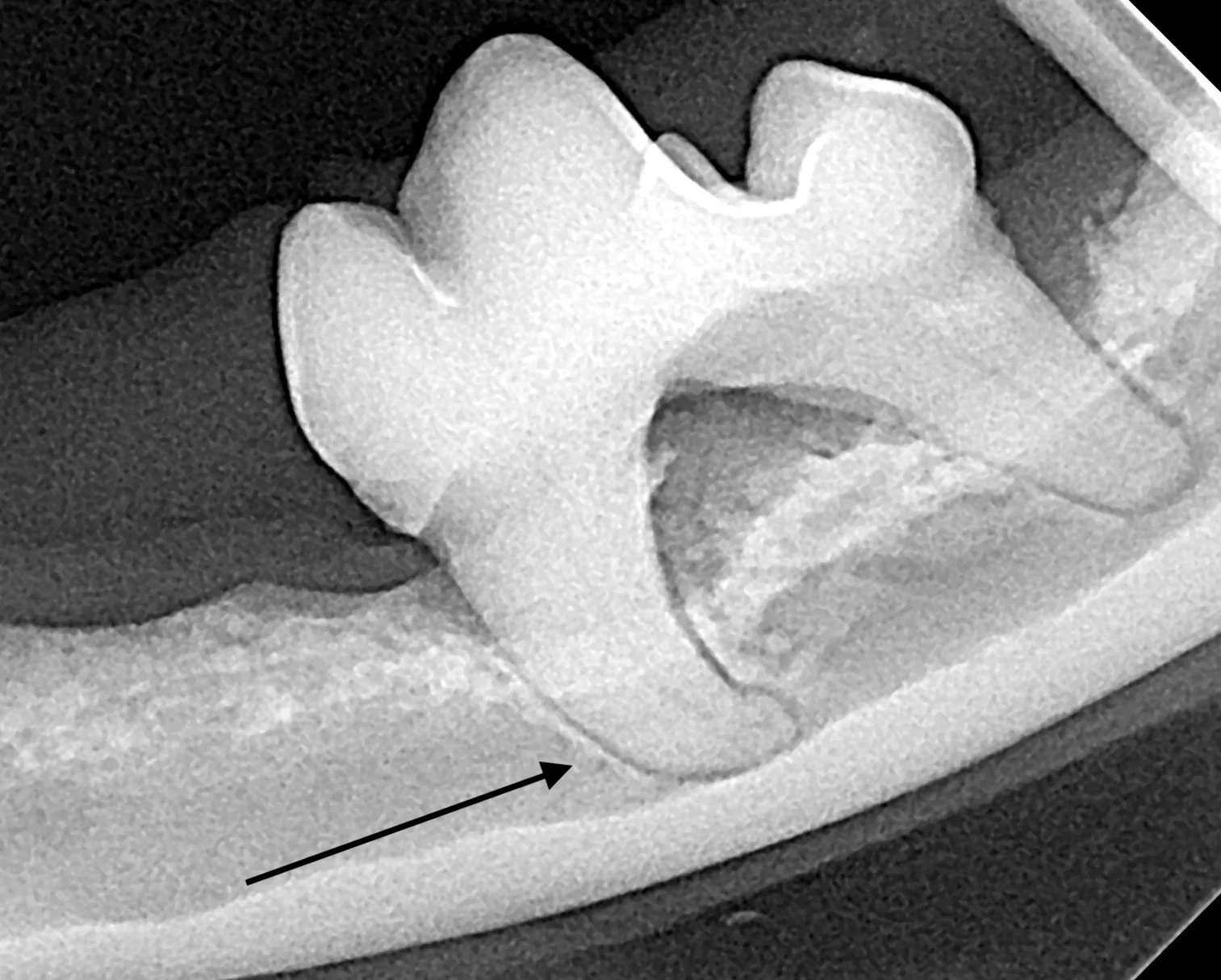

4. Tooth Root Fracture

Root ankylosis, root resorption, root dilaceration (ie, curvature), and/or bulbous roots can increase the difficulty of a tooth extraction (Figure 12). Tooth roots occasionally break during extraction attempts. Diseased tooth roots should typically not be left in place due to the potential for pain and infection.5 Safe root extraction includes removal of additional alveolar bone or widening of the alveolus with a high-speed bur to create a moat around the remaining root fragment prior to lifting it out (see Suggested Reading).5

Root ankylosis (A), root resorption (B), bulbous root (C; arrow), and root dilaceration (ie, curvature) (D; arrow) are tooth root anomalies that can increase the difficulty of tooth extraction.

Root tips may be easily displaced into the mandibular canal or the nasal passage and maxillary sinus. Displacement is more likely with significant oral disease or bone loss around the root apex. Roots displaced into abnormal locations should be removed surgically by a board-certified veterinary dentist.

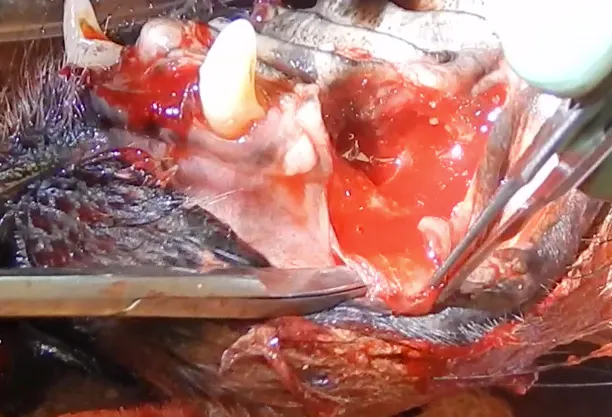

5. Bleeding

Significant bleeding during a dental procedure most commonly occurs following damage to one of the large vessels that supplies the oral cavity. Familiarity with oral anatomy and understanding of the location of the infraorbital artery, middle mental artery, inferior alveolar artery, major palatine artery, and incisive artery, are therefore important, as these vessels are most likely to be damaged during routine dental procedures.

If bleeding is severe, the vessels may be ligated; however, they often cannot be isolated because they retract into the bone once damaged. Intractable bleeding can be managed by packing off the area with a sponge or clotting material (eg, absorbable hemostatic gelatin sponges, bone wax) for 10 to 15 minutes. In cases in which the extraction procedure must be stopped, extraction can be attempted again after 3 to 6 weeks, or the patient can be referred to a board-certified veterinary dentist for additional care.

Conclusion

Dental disease is common in veterinary patients, and recognizing common complications of treatment can help general clinicians obtain training to avoid and manage these adverse outcomes.

Listen to the Podcast

Dr. Babbitt shares his best tips for preventing the most common issues associated with dental procedures.