Cytotoxic Chemotherapeutic Agents

Chemotherapy in Veterinary Medicine

Primary goal: Enhance or maintain quality of life.

Secondary goal: Stabilize, decrease, or eliminate neoplastic process.

Client comfort level varies by individual—some clients will want to take a “go out with guns blazing” approach, while others will not tolerate even mild adverse events (side effects) in their pets.

Studies assessing clients’ perceptions of medical treatment for cancer in their companion animals generally report a positive experience; most felt treatment was worthwhile and resulted in improvement in the well-being of their pets, and that quality of life during treatment was good.

Basic ConceptsMost cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs target rapidly dividing cells.

This represents an opportunity—tumor cells are rapidly dividing.

It also represents an obstacle—some normal cells are rapid dividers and are therefore at risk for adverse effects.

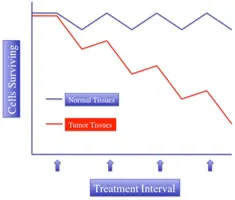

Due to the cytotoxic action of most chemotherapy, single high doses that would kill all cancer cells would also seriously harm normal tissues; therefore, a fractionated approach to treatment must be employed (Figure 1):

Try to maximize tumor kill and minimize host adverse events.

A given dose kills a constant fraction of cancer cells (each dose kills 2–4 logs).

Normal cells generally heal faster and more completely than cancer cells; hence, the steeper upward slope of repair in normal cells and more shallow slope of killing shown in Figure 1.

Fractionating treatment allows recovery of normal tissues between treatment intervals.

The treatment and the interval between treatments are collectively called a cycle.

Figure 1: Graph illustrating the differential cell kill and repair of normal tissues in comparison to tumor tissues. The slope of cell kill is generally steeper in tumor tissues, while the slope of cell repair is steeper in normal tissues. This difference allows for theorized tumor eradication in the face of normal tissue healing.

Roles of Chemotherapy

Induction therapy: For a measurable tumor with known sensitivity (eg, lymphoma)

Adjunct to local therapy: Aim to eradicate occult micrometastasis or microscopic residual local disease after primary tumor is surgically addressed (eg, osteosarcoma post amputation, hemangiosarcoma post splenectomy).

Primary (neoadjuvant) therapy: Administering chemotherapy prior to definitive surgery to “downstage” or shrink the tumor to a more manageable size (eg, downstaging thymoma or mast cell tumors)

Palliation: While cure or extension of lifespan is not possible, treatment will return the patient to a better quality of life (eg, advanced metastatic disease where the shrinking of tumor at one location may relieve obstructive consequences, such as airway or urinary obstruction)

Client EducationClient education is extremely important when using chemotherapy:

Clearly define the strategy and explain the goals.

Allow appropriate time to decide on available options.

Use handouts, including those explaining body fluids/feces disposal, safe handling, and how to manage adverse events.

Continually have client assess quality of life through the use of simple questionnaires.

Medications

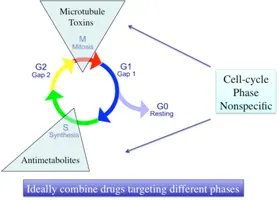

Commonly Used Chemotherapy AgentsAlthough there is some overlap, agents can be classified by general mode of action or wherethey act within the cycle of dividing cells (Figure 2):

Figure 2. Different classes of chemotherapy attack cells in different parts of the cell cycle. Some are cell-cyclephase–specific (eg, microtubule toxins are “mitosis”-specific; antimetabolites are Sphase–specific) and others kill cells at any point in the cell cycle (phase-nonspecific).

Antimitotics/microtubule toxins: Disrupt or immobilize the mitotic spindle.

Generally cell-cycle-phase–specific (mitosis)

Includes the vinca alkaloids (eg, vincristine, vinblastine) and the taxanes (eg, paclitaxel and docetaxel)

Alkylating agents: Bind DNA strands, insert an alkyl group, and change the structure of DNA sufficiently to interfere with transcription, replication, and repair machinery

Cell-cycle-phase–nonspecific

Includes cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, CCNU, melphalan, dacarbazine

Antibiotic agents: Several mechanisms of action:

Cell-cycle-phase–nonspecific

Includes doxorubicin, mitoxantrone,actinomycin-D, idarubicin

Antimetabolites: Generally nucleotide analogs or substrates of active metabolic processes within the cell.

Cell-cycle-phase–specific synthesis

Includes methotrexate, gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, cytosine arabinoside

Use of Combination ChemotherapySingle agents do not cure (rare exceptions, eg, transmissible venereal tumor); therefore, combination protocols are most effective. The use of multiple drugs reduces risk for chemoresistant clones.

Guidelines for using combination chemotherapy protocols:

Only use if proven efficacy as single agent.

Do not add a drug if it means lowering the dose of another known effective drug.

Avoid overlapping toxicities.

Combine drugs with different mechanisms of action.

Safe Handling

Most cytotoxic chemotherapy agents are both mutagenic and carcinogenic and deserve a healthy respect. Risk is low but real; therefore, minimizing exposure is prudent.

Follow local, regional, and federal guidelines for disposal that apply to your practice area.

Clear guidelines for the protection for self, staff, client, and the client’s family should be in place and referred to regularly.

Veterinary Staff

Educational in-service meetings should be held regularly to bring staff up to date on policies.

Injectable drugs should be reconstituted in approved airflow hoods or through the use of commercial systems (eg, Phaseal system, carmelpharma.com).

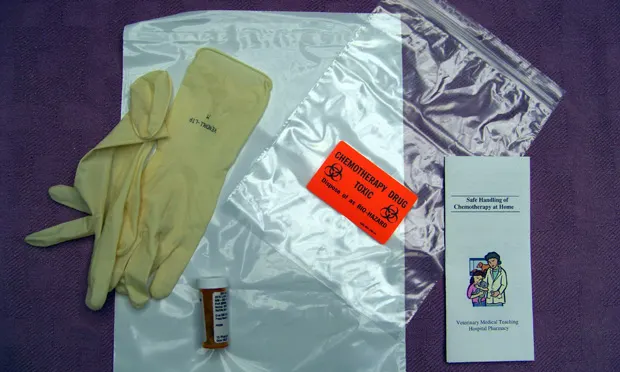

Upon mixing and prior to dosing, drugs should be packaged in zip-closure plastic bags clearly marked with a chemotherapy hazard sticker (Figure 3).

A consistent, low-traffic area of the hospital should be designated for drug delivery.

Approved gloves, gowns, and goggles should be used during dosing.

Hospitalized patients that have received chemotherapy should have cage labels clearly indicating a biohazard.

A clearly marked “spill kit” should be available.

Staff who are pregnant or trying to become so should avoid contact.

Figure 3. When sending home chemotherapeutic agents, packaging within clearly marked bags, along with approved chemotherapy gloves and educational handouts, is recommended.

Clients & Families (first 48 hours post dosing)

Clients who are pregnant or trying to become so and children should avoid contact with animals and their bodily fluids.

Send home clear and understandable handouts on safe handling of pets, bodily fluids, and take-home drugs, as well as a supply of chemotherapy-approved gloves.

Drugs should be packaged in zip-closure plastic bags clearly marked with a chemotherapy hazard sticker. Store drugs away from food.

Instruct client to:

Wash hands after dosing and after removing gloves.

Make sure animal swallows medications.

Wash contaminated laundry separately.

Clean up feces frequently and dispose in toilet for 48 hours after treatment.

Adverse Events (AEs)AEs generally occur as a result of collateral damage to rapidly dividing cells by antiproliferative cytotoxic agents.

Dividing bone marrow cells—myelosuppression, in particular neutropenia and, less so, thrombocytopenia

Gastrointestinal crypt cells—vomiting, diarrhea, inappetence

Hair follicle cells—hair loss in nonshedding breeds (poodles, old English sheepdogs, some terrier breeds) is common (Figure 4); uncommon in shedding breeds

Figure 4. Nonshedding breeds, such as poodles (pictured here), lose hair during chemotherapy, while shedding breeds are not likely to lose hair.

Most protocols in common veterinary use are designed to have a low risk of AEs.

Approximately 3% to 5% of patients will have a serious AE, leading to hospitalization.

The risk of treatment-associated fatality is less than 1 in 200.

Important consequences of serious AEs may result from application of chemotherapy:

Decreased quality of life

Financial consequences (eg, hospitalization and treatment)

Delay or reduction of subsequent effective treatments

Diminished client enthusiasm for continuation of therapy.

Aggressive preemptive measures can be taken to decrease the incidence of significant AEs.

Should a serious AE occur, dosage can be reduced, drugs can be substituted, or additional medications dispensed to minimize the likelihood of further AE.

Some breeds are at increased risk for AEs from chemotherapy:

Collies and some other herding breeds (eg, Shetland sheep dog, Australian shepherd) may have a mutation in their normal cellular drug-clearance pump (MDR1 gene).

A cheek-swab genetic test for the MDR1 mutation is available and should be considered in breeds at risk prior to giving chemotherapy that is derived from natural products (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and the taxanes).

Because the therapeutic index of most cytotoxic chemotherapy agents is narrow, it is critical to avoid dosing errors. The “4 R’s” should be considered prior to any chemotherapy treatment:

Right drug

Right dose

Right route

Right patient.

Prevention & Treatment of Adverse EventsSee Suggested Reading for more thorough discussions on managing and preventing AEs. Discussion with a board-certified medical oncologist is prudent prior to using chemotherapeutic agents.

Perivascular necrosis: Several chemotherapeutic agents are vesicants and can cause significant perivascular necrosis if given outside the vein. If perivascular drug delivery is noted:

Read the package insert for potential treatment measures.

Consider immediate debridement of tissue.

Consider immediate systemic dexrazoxane therapy if doxorubicin is the agent.

Contact a board-certified medical oncologist.

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting:

NK1-receptor antagonist antiemetics (eg, maropitant) are most effective; begin the day after chemotherapy and continue for 4 to 5 days.

Add other antiemetic classes if breakthrough vomiting occurs (eg, ondansetron, metoclopramide).

Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia:

Occurs to some extent in all dogs.

The nadir (low point) usually occurs 5 to 7 days after chemotherapy.

Subsequent chemotherapy should not be given until neutrophil counts return to levels above 1500/mcL.

Antibiotic therapy is indicated if the neutrophil count at nadir is below 1000/mcL and/or if illness or fever is present.

In General

Relative CostCosts of chemotherapy vary widely based on the agent chosen or tumor type. Treatment costs include a combination of:

Drug costs: $$ to $$$$

Pretreatment and nadir CBC to ensure adequate neutrophils and platelets: $$

Administration fees: $$ to $$$

Drug and injectable disposal: $

CYTOTOXIC CHEMOTHERAPEUTIC AGENTS • David M. Vail

Suggested Reading

1. Aftershocks of cancer chemotherapy: Managing adverse effects. Thamm DH, Vail DM. JAAHA 43:1-7, 2007.

Breed distribution and history of canine mdr1-1Delta, a pharmacogenetic mutation that marks the emergence of breeds from the collie lineage. Neff MW, Robertson KR, Wong AK, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11725-11730, 2004.3. Cancer chemotherapy. Chun R, Garrett LD, Vail DM. In Withrow SW, Vail DM (eds): Small Animal Clinical Oncology, 4th ed—St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, pp 163-192, 2007.4. Cytotoxic chemotherapy: New players, new tactics. Vail DM, Thamm DH. JAAHA 41:209-214, 2005.5. Owners’ assessments of their dog’s quality of life during palliative chemotherapy for lymphoma. Mellanby RJ, Herrtage ME, Dobson JM. J Small Anim Pract 44:100-103, 2003.6. Owners‘ perception of their cats’ quality of life during COP chemotherapy for lymphoma. Tzannes S, Hammond MF, Murphy S, et al. J Feline Med Surg 10:73-81, 2008.7. Study of dog and cat owners’ perceptions of medical treatment for cancer. Bronden B, Rutteman GR, Flagstad A, Teske E. Vet Rec 152:77-80, 2003.

Supportive therapies in veterinary oncology. Vail DM. Top Companion Anim Med, in press, 2009.9. Veterinary Cooperative Oncology Group-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (VCOG-CTCAE) following chemotherapy or biological antineoplastic therapy in dogs and cats v1.0. Veterinary Cooperative Oncology Group. Vet Compar Oncol 2:194-213, 2004.