Cryptococcosis: An Overview

This article is part of the One Health Initiative.

Profile

Definition

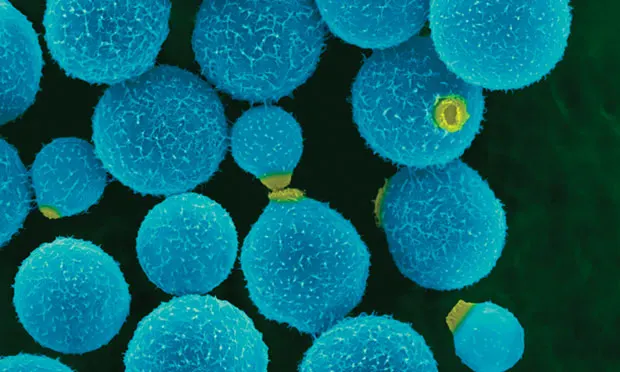

Cryptococcosis, the most common systemic mycosis in the domestic cat, is caused by an encapsulated yeast—most commonly Cryptococcus neoformans and C gattii, both dimorphic, basidiomycetous fungi.

C neoformans.

C neoformans var neoformans.

C neoformans var grubii.

Genotyping via PCR fingerprinting is used to distinguish molecular types and differentiate strains based on geographic location.

C neoformans var grubii isolates are molecular types VNI and VNII.

C neoformans var neoformans is type VNIV with a hybrid type VNIII.

C gattii isolates are classified as molecular types VGI–VGIV with different genetic subtypes within each VG group representing various strains.

Reproduction occurs with asexual and sexual phases.

Asexual phase is haploid.

Sexual phase is by budding.

Found within mammalian tissue.

Production of basidiospores (ie, infectious component of Cryptococcus).

Systems

Upper respiratory (ie, nasal cavity), skin, lymph nodes, brain, meninges, and eyes are the most common infection sites.

Other sites include lungs, mediastinum, gingiva, spleen, myocardium, liver, thyroid gland, tongue, and bone.

Geographic Distribution

Australia, western Canada, and western United States.

Although less prevalent, Cryptococcus spp can occur in all parts of the world.

Signalment

Species

Most common in cats and dogs; other mammalian species are susceptible.

All domestic cats are at risk.

Breed

Siamese, Birman, and Ragdoll cats were overrepresented in a study from Australia.<sup1, 2sup>

No breed predisposition was found in a study in California.2,3

Age

Cats of all ages are known to become infected.

Young adult cats appear at increased risk (2–3 years of age).

Median age at infection is 6 years.2-4

Exposure can occur years before infection materializes, so older cats may present with signs.

Predominantly younger, more active dogs are at increased risk.

Sex

No known sex predilection.

Causes

Inhalation of spores from avian guano or affected soils.

C neoformans is also found in decaying plant matter harboring in some tree hollows.

C gattii has been isolated from air, seawater, freshwater, and tree bark.

Risk Factors

Cats with retroviruses (ie, FeLV, FIV) are not predisposed to infection with Cryptococcus spp, but difficulty responding to therapy and relapse of cryptococcosis may be common.2,5

These patients may be predisposed to neoplasms (eg, lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, mast cell tumor).

Opportunistic infections (eg, from Toxoplasma gondii) have been reported.

Pathophysiology

Encapsulated spores (basidiospores) are typically inhaled, initiating infection in the nasal cavities of cats (primarily) and dogs.

Disease can spread through the cribriform plate, causing meningitis.

May involve the optic nerve and eye.

May extend into lungs, skin, bones, brain, and other body sites via hematogenous routes.

May be detected in the lungs via histopathology without producing clinical signs.

Direct contact with open wounds may cause skin lesions.

Multiple granulomatous skin lesions are more likely associated with hematogenous spread.

History

Outdoor cats more susceptible.

Indoor cats exposed from open windows/doors or indoor plants/soil.

Transfer from clothing can occur.

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid

Signs

Sneezing, head shaking, stertor.

Inappetence from blocked sinus passages and invasion into the CNS.

Blindness.

Figure 1A, Cat presented with classic nasal lesions consistent with cryptococcosis. Courtesy of Patricia Ashley, DVM, DACVD

Physical Examination

Findings in cats (See Figure 1):

Infection with C gattii VGI and C neoformans var grubii may be localized to the nasal cavity.

Infection with C gattii VGII genotypes can involve multiple organs.

Swelling over nasal maxillary of frontal area.

Proliferative lesions in the nares.

Fungal granulomas in lymph nodes and skin (primarily around head and neck).

Mydriasis and optic disc or retinal lesions.

Figure 1B, Signs improved after 7 months of treatment with fluconazole. Courtesy of Patricia Ashley, DVM, DACVD

Findings in dogs:

Signs involving multiple organ systems.

Neurologic signs, often in conjunction with malaise, are most common:6

Stumbling.

Partial paralysis.

Ataxia.

Hyperesthesia along dorsum or cervical area.

Seizures, sometimes severe.

Blindness less common than in cats.

Approximately 50% have upper respiratory signs:6

Epistaxis.

Sneezing.

Nasal discharge.

GI signs.

Renal involvement.

Cutaneous lesions.

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

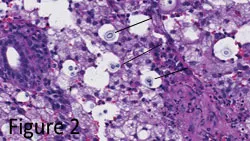

Cytologic evaluation of tissue samples.

Rapid, inexpensive, sensitive test.

Does not permit identification of Cryptococcus spp.

Narrow-based budding yeast capsules evident (See Figure 2).

Culture of samples from nasal swab, needle aspiration, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), lymph nodes, pleural and/or abdominal fluids, urine.

Organism grows readily in standard culture media and is not a hazard to laboratory personnel.2

Cryptococcus spp will not grow on dermatophyte medium containing cycloheximide.

Use of selective medium can differentiate C neoformans group from C gattii.

Immunohistochemical staining cannot distinguish various C gattii strains from Pacific Northwest.

Can use with titers to evaluate treatment outcome.

Antigen titers in serum and CSF are highly specific and sensitive.

Aid in diagnosis and determining response to therapy.

Initial rise in titers after treatment is expected.

Titers should be rechecked 6–8 weeks after initiating therapy.

Therapy should be continued until titers are negative; relapse is possible.

Differential Diagnosis

Infectious rhinitis.

Bacterial.

Viral.

Parasitic.

Inflammatory rhinitis.

Foreign object.

Lymphoplasmacytic.

Eosinophilic.

Other.

Neoplasia.

Nasal lymphoma (more common in cats).

Nasal adenocarcinoma (more common in dogs).

Laboratory Findings

CBC and serum biochemistry findings are nonspecific:

Low-grade nonregenerative anemia.

Lymphopenia.

Monocytosis.

Occasionally elevated globulins (polyclonal gammopathy).

CSF analysis.

May have encapsulated yeast.

Mild to moderate protein elevations.

Neutrophilic pleocytosis.

Imaging

Thoracic radiography.

Assess for pulmonary infiltrates, enlarged lymph nodes, mediastinal changes, and effusions from systemic fungal infection.

Abdominal ultrasonography.

Normal in >80% of cats with cryptococcosis.

Iso-hypoechoic mass lesions in the renal pelvis in cats with renal involvement may be visible.

MRI.

Helps assess extent of CNS involvement, including mass lesions and optic nerve enlargement.

CT.

Helps assess destruction of cribriform plate and bony structures of the face.

May have contrast-enhancing mass lesions of the nasal planum; soft tissue and fluid opacification are also possible.

Also helps assess extent of CNS involvement, including mass lesions and optic nerve enlargement.

Treatment

Supportive care for anorexic and dehydrated patients should be administered as necessary.

Surgery:

May be beneficial to cats with large accessible cryptococcomas if medications do not penetrate the lesions.

Is controversial as some cats respond to antifungal therapy (see Medications, next page).

Nutritional Aspects

Feeding tubes (eg, PEG, E-tubes) may be indicated to supply nutritional support until inflammation in the nasal passages subsides with antifungal therapy.

Client Education

Treatment duration is long and owner compliance with medications and follow-up is imperative.

Zoonotic transmission of Cryptococcus from a pet cockatoo to an immunocompromised person has been reported.7

Transmission is via aerosol exposure from bird excreta rather than direct contact with the animal.8

Cryptococcosis is the most common opportunistic fungal disease of humans with HIV.8

Other sources indicate no zoonotic potential to immunocompetent individuals.6-9

Transmission occurs via shared contaminated environments.6

Medications

Azoles

Fungistatic compounds that alter cell membrane permeability and allow cell contents to leak into the periphery.

Fluconazole is treatment of choice for maximum penetration into the CNS, eye, and urinary tract with minimal side effects.

Standard dose for dogs and cats is 5 mg/kg PO q12h until antigen testing of blood or CSF (if CNS disease is present) is negative (mean duration, 8 months).8

Some cryptococcal isolates show resistance.

Itraconazole has been used successfully to treat cryptococcal meningitis.

Cats may experience anorexia, vomiting, and hepatocellular damage (all dose-dependent).

Oral suspension has greater bioavailability and should be dosed lower than tablet formulation (3 mg/kg PO q24h rather than 10 mg/kg PO q24h).

Compounded formulations have been associated with inadequate blood levels.

For cats with localized disease and resistance to fluconazole, ketoconazole may be preferred by cost-conscious owners.

Standard dose of ketoconazole for dogs and cats is 5–10 mg/kg PO q12–24h until antigen testing of blood or CSF (if CNS disease is present) is negative (~6–18 months).8

Other azoles (eg, voriconazole, posaconazole) are effective but expensive.

Cats may experience neurologic effects from voriconazole.

Amphotericin B

Fungicidal compound that also disrupts fungal cell membranes.

Must be given parenterally.

SC protocol may minimize hospitalization and permit outpatient care.

0.5–0.75 mg/kg diluted in large volumes of 0.45% NaCl and 2.5% dextrose 2–3 times/week.

Median cumulative dose of 16 mg/kg.

Newer liposomal and lipid complex preparations are less nephrotoxic than previous formulations.

Flucytosine

Pyrimidine analog that interferes with fungal nucleic acid synthesis.

Standard dose (cats only) is 30 mg/kg PO q6h, 50 mg/kg PO q8h, or 75 mg/kg PO q12h, not to exceed 250 mg q6–8h.8

Should not be used as a monotherapy because of risk for resistance.

May cause bone marrow suppression, GI disturbance, and worsening of preexisting renal insufficiency.

Should not be used in conjunction with amphotericin B.

Use only in cats; dogs tend to develop severe cutaneous drug eruptions.

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid

Follow-up

Complications

Hepatocellular damage associated with chronic ketoconazole and itraconazole administration is possible and warrants monthly monitoring of liver enzymes.

Renal toxicity associated with amphotericin B is possible and warrants monthly monitoring of renal values and consideration of using liposome-encapsulated formulations of amphotericin B to reduce risk for renal toxicity.

Future Follow-up

Serum antigen titers should be monitored monthly for seroconversion during treatment.

Patients that seroconvert to a negative status should be retested 1 month after therapy.

Successful treatment occurs when the titer reaches zero.

Treatment may be indicated for months to years.

For cats in carrier state, periodic antigen testing is warranted.

Antigen titer should decrease by 1 dilution each month during therapy.

Failure to achieve this suggests the need for more aggressive therapy (ie, additional medications or change in protocol).8

In General

Relative Cost

Treatment is costly, as it is required for months to years: $$$$$

Fluconazole and ketoconazole are less expensive than itraconazole.

Prognosis

Animals that survive the first 2 weeks of therapy have a reasonable but guarded prognosis.

Rapid rate of improvement in the first month can lead to decreased owner compliance, precluding a higher rate of relapse.

Relapse is possible.

CNS involvement is the only significant predictor of mortality.

REBECCA NORTON, DVM, is resident in small animal internal medicine at Gulf Coast Veterinary Specialists in Houston, Texas. Her areas of interest include fungal and GI diseases. She received her DVM at University of Minnesota and completed an internship at Dogs and Cats Veterinary Referral in Bowie, Maryland.

DEREK P. BURNEY, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, is affiliated with Veterinary Specialists of North Texas in Dallas. His areas of interest include feline medicine and parasitology. Dr. Burney completed a one-year internship at Auburn University followed by a residency in small animal internal medicine and PhD in molecular parasitology at Colorado State University. He earned his DVM from Texas A&M University.

CRYPTOCOCCOSIS • Rebecca Norton & Derek P. Burney

References

1. Retrospective study of feline and canine cryptococcosis in Australia from 1981-2001: 195 cases. O’Brien CR, Krockenberger MB, Wigney DI, et al. Med Mycol 42:449-460, 2004.

2. Feline cryptococcosis: Impact of current research on clinical management. Trivedi SR, Malik R, Meyer W, Sykes JE. J Feline Med Surg 13:163-172, 2011.

3. Clinical features and epidemiology of cryptococcosis in cats and dogs in California: 93 cases (1988-2010). Trivedi SR, Sykes JE, Cannon MS, et al. JAVMA 239:357-369, 2011.

4. Cryptococcosis in cats: Clinical and mycological assessment of 29 cases and evaluation of treatment using orally administered fluconazole. Malik R, Wigney DI, Muir DB, et al. J Med Vet Mycol 30:133-44, 1992.

5. Cryptococcal infection in cats: Factors influencing treatment outcome, and results of sequential serum antigen titers in 35 cats. Jacobs GJ, Medleau L, Calvert C, Brown J. J Vet Intern Med 11:1-4, 1997.

6. Cryptococcosis: Update and emergence of Cryptococccus gattii. Lester SJ, Malik R, Bartlett KH, Duncan CG. Vet Clin Pathol 40:4-17, 2011.

7. Evidence of zoonotic transmission of Cryptococcus neoformans from a pet cockatoo to an immunocompromised patient. Nosanchuk JD, Shoham S, Fries BC, et al. Ann Intern Med 132:205-208, 2000.

8. Cryptococcosis. Sykes JE, Malik R. In Greene CE (ed): Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 4th ed—St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2012, pp 621-634.

9. Cryptococcus species—etiological agents of zoonoses or sapronosis? Blaschke-Hellmessen R. Mycoses. 43 suppl 1:48-60, 2000.